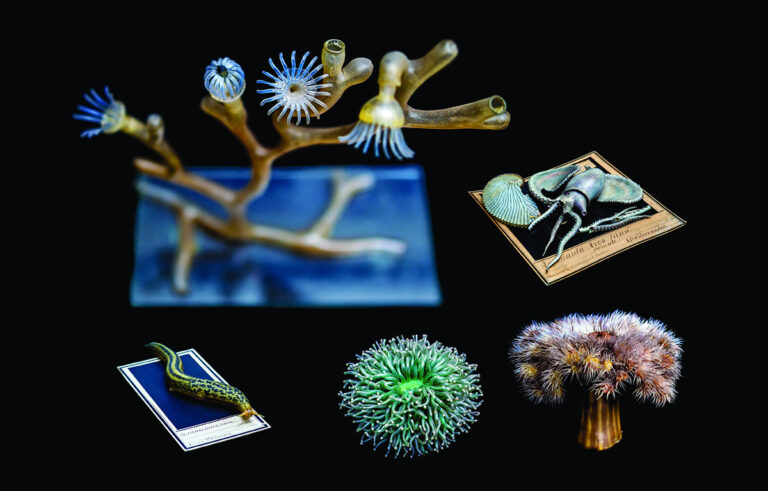

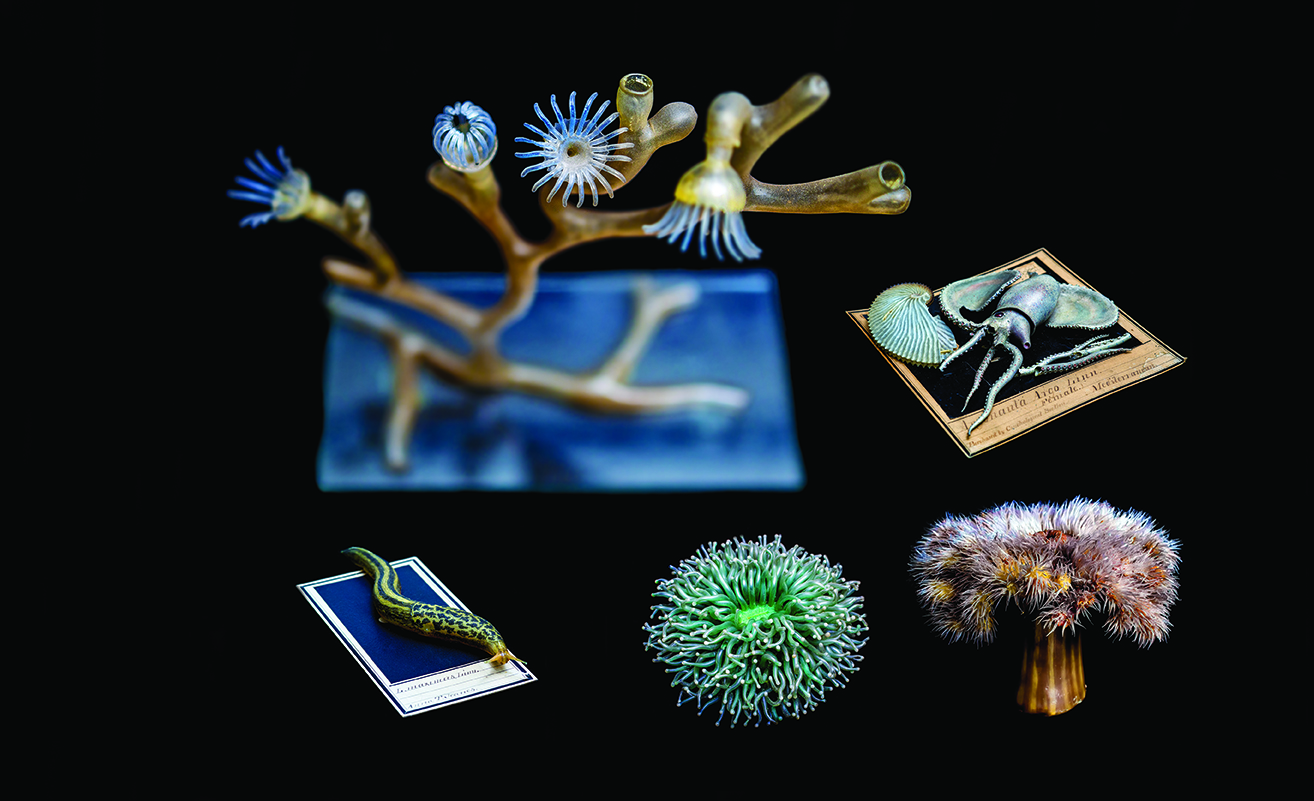

In the 1800s, the scientific study of marine life depended on life-like, glass-blown models created by master artisans Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka — and today Drexel is one of only a handful of universities with a collection of the delicate, beautiful Blaschka originals.

The scientists of the 19th century had a quandary. How do you preserve exceedingly fragile and perishable aquatic specimens like sea anemone for long-term study? Preservation in alcohol was one solution, but that robbed the delicate creatures of their color and form, and if allowed to dry out they become little more than raisins.

The answer arrived in the form of father-and-son artisans Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, two master glassworkers who parlayed their expertise as jewelers into creating extraordinarily detailed and accurate glass reproductions of scientific specimens for museums and research organizations. Working from Dresden over a 30-year period, the pair produced more than 700 models, each made to order and sold through dealers like Ward’s Natural Science Establishment of Rochester, New York.

In 1879, Academy scientist Joseph Leidy wrote in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences that the Blaschka models are “remarkable for their accuracy and beauty…They represent soft and delicate forms which cannot be satisfactorily preserved, and others too minute to be examined with the naked eye. Moreover, their price is so moderate, that it is to be hoped that the Academy may make early provision to obtain a series.” Leidy placed an order that same year.

Unfortunately for the fragile figurines, preserving them intact for many generations is difficult. Due to poor storage conditions and the delicacy of the materials, the Academy’s collection of Blaschka glass has deteriorated over time. Glass experts have had great success restoring these materials and Academy archivists hope to someday embark on a similar conservation project for its own Blaschka collection.

“Unfortunately, the Blaschkas don’t come out much anymore,” says Jennifer Vess, the Academy’s Brooke Dolan Archivist. “Some of the more complex pieces have been damaged. We would very much like to have those conserved so they can come out on display more often.”