On a recent day on the job, one of Hakim Pitts’ coworkers became concerned about a man who seemed a little disturbed.

The man “wasn’t doing so well,” the coworker told Pitts, who is an outreach and enrollment specialist for a walk-in health clinic inside a North Philadelphia ShopRite. “He may need someone to talk to.”

The man wasn’t a patient — he was standing around outside the building — but Pitts walked outside to speak to him anyway. The man was a veteran, it turned out. He told Pitts he didn’t feel well and when Pitts pressed him, he admitted to feeling suicidal.

Pitts then asked the man a crucial question: “Do you have a suicide plan?”

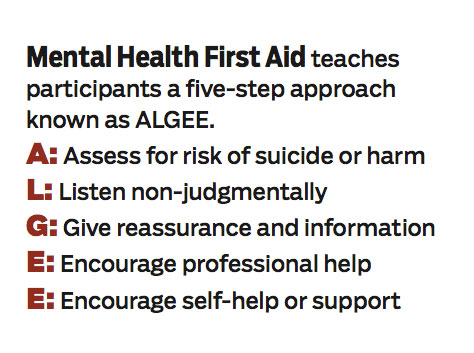

Not everyone would be so direct. But Pitts had been coached to ask that question through the city’s “Mental Health First Aid” training program, part of an ambitious citywide initiative to educate citizens and city workers about the signs and symptoms of mental illness and provide them with tools to help those in need get treatment.

The program was adopted by the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services two years ago in partnership with Drexel University’s School of Public Health, which is in the midst of an evaluation study of its effectiveness. Philadelphia’s goal is to train 10,000 individuals — ranging from ordinary citizens to public health workers to law enforcement officers and school police — within the first two years.

Longer term, the city’s goal is to train 100,000 — making Philadelphia’s the largest rollout of the program in the United States.

Pitts eventually determined that the man needed an intervention, so he phoned the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services and a “mobile emergency team” quickly arrived. The team, which has the authority to make an involuntary commitment if necessary, offered the man help and resources and saw him on his way.

Before the man left, Pitts gave him his phone number. “If you’re feeling bad like that again,” Pitts told him, “you can come back here and talk to me.'”

Reflecting on his training, Pitts recalls it opened his eyes to how common mental health challenges are, especially in the African-American community he grew up in. The knowledge was “inspiring,” he says.

“Growing up, I often thought I was alone,” he says. “Mental health isn’t something that’s discussed.”

FEAR AND LOATHING

Most people would hesitate to approach a troubled stranger, much less ask probing personal questions.

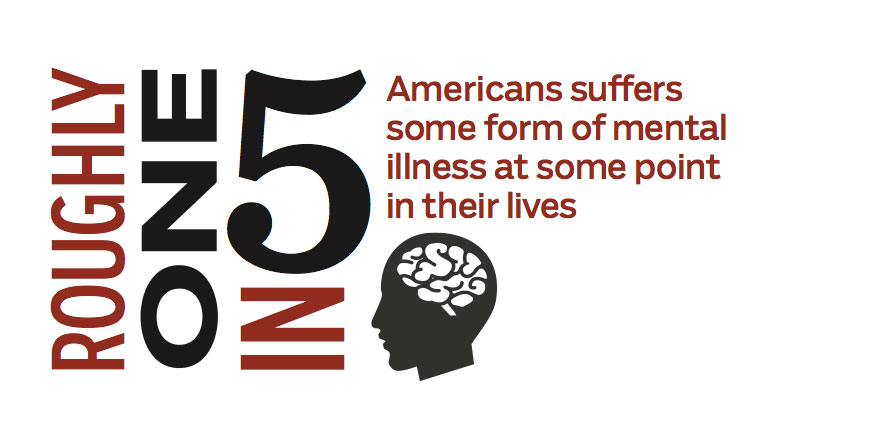

Though mental illness touches almost everybody — roughly one in five Americans suffers a form of it at some point in their lives — the subject often percolates to public attention only when it’s too late, in the aftermath of a tragic shooting or a high-profile suicide.

Reducing the stigma surrounding the subject is one of the biggest challenges in the health care field, says Arthur Evans, who heads the city’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual DisAbility Services and administers the Mental Health First Aid program.

Many people view the mentally ill as dangerous, hard to talk to, or as being responsible for their condition. Stigma deters people experiencing a mental health crisis from seeking treatment, and two thirds suffer in silence, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“People have a misconception about [it], that it’s untreatable, that if you have a mental illness, you have it for life, and you’re not going to do well — but the research says that most people in fact recover,” says Evans.

In recent years, a growing number of public agencies have turned to Mental Health First Aid and programs like it to educate their employees and the public about mental health issues.

“In [wealthy] communities, you can really focus on the aspects of the condition specific to a person’s illness. But in Philadelphia, you not only have to deal with that but you often also have to think about basic needs: Does the person have a place to stay? Do they have the basics that they need for living?”

— Arthur Evans

As the name suggests, the idea at the heart of the Mental Health First Aid training program is to train people to respond to someone experiencing a mental health problem or a crisis — an individual contemplating suicide or a friend in the throes of depression — with immediate assistance, just as they would a choking or burn victim.

“If someone has a heart attack, there are 10 people there to provide CPR,” says Evans. “If someone starts to exhibit psychiatric signs, people typically go the other way.”

First developed in 2000 in Australia, the Mental Health First Aid program was brought to the United States in 2008 by the National Council for Committee Behavioral Health, and it has since been implemented around the country.

Rhode Island has made it part of police officer training. Texas offers it to every public library employee. The White House called for teachers and other adults working with youth to receive the training as part of President Obama’s 2013 plan for reducing gun violence. It’s even being translated into Spanish.

No U.S. city has committed to it as thoroughly as Philadelphia. Since the city’s kick off in 2012, Philadelphia has overseen between 25 and 30 trainings per month — nearly one a day — and trained roughly 5,000 people, already half the city’s stated goal.

More than 200 people have undergone a weeklong program to become instructors, who in turn train more “First Aiders.” Among the first to take the course were Philadelphia School District security officers. All new recruits to the Philadelphia police and fire departments are getting the training this year as well. Instructors are also fanning out to organizational hubs such as the Red Cross, the Philadelphia Department of Human Services, hospitals, universities and others.

The trainings, Evans says, “show people, ‘OK: Here are the illnesses, here are the symptoms, here are the treatment options, here are the self-help groups’ … so that when people start to show signs, there are other people in their communities who know how to respond.”

Twenty percent of people are going to have some mental health challenge in their lifetimes, says Evans. “We want their communities not to shut them out but to embrace them, to understand mental illness and how to support them.”

But despite the program’s wide adoption around the country, minimal data has been collected to measure its impact.

How are participants applying what they learned at work, at home, in their neighborhoods and congregations? To

what extent is it likely to translate into action and better public health?

That’s where Drexel’s Nancy Epstein comes in.

DOES IT WORK?

As principal investigator of the evaluation study, Drexel School of Public Health Associate Professor Nancy Epstein is looking at the impact of the program on people’s behavior and attitudes, with the goal of determining whether it results in the kind of prevention and early intervention that allow individuals to get help before their problems escalate into addiction, self-harm or violence.

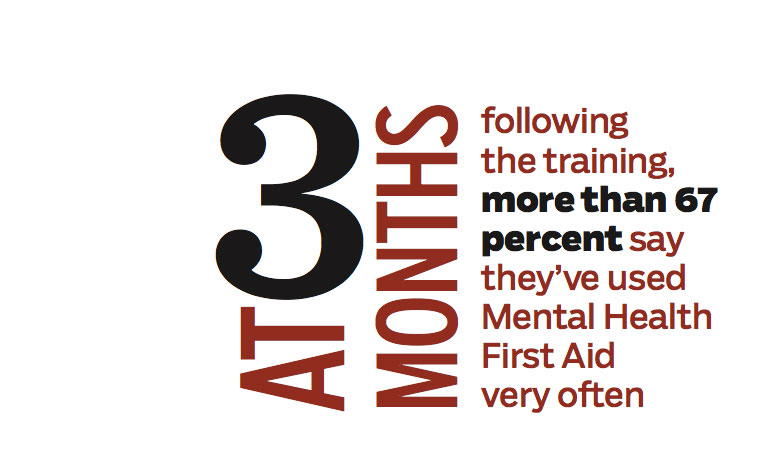

Epstein and her team have begun conducting online surveys of First Aiders both three and six months after they’ve undergone the training, in addition to telephone interviews.

“There’s a lot to learn,” says Epstein. “Philadelphia is doing something that’s happening already in many places across the country, at the state level, at the national level, even internationally. In any publicly funded program, it’s really important to have an evaluation, to know what’s happening.”

The study is unfinished and still too much in its beginning stages to draw broad conclusions, says Epstein. However, early results indicate that the program has — at least as reported by those who’ve taken it — made a difference, sometimes a profound one, among its participants.

After surveying more than 300 First Aiders since February of this year, Epstein says that what she’s found so far “is really striking.”

“Without fail, every person I’ve interviewed said [the training] was making a difference in their lives — that they had gained valuable skills that they were using,” she says.

A high percentage of the people responding to the surveys so far (which have an impressive 27 percent response rate) reported using what they’d learned in the time since the training. At three months following the training, more than 67 percent say they’ve used Mental Health First Aid very often. At six months, 34 percent reported using it six or more times.

Significantly, the Drexel team has also documented a 30 percent decline in attitudes of stigma.

Trainees have self-reported experiencing less feeling of stigma around mental illness, as reflected in their own answers to questions like whether they would sit next to someone who was showing signs of mental illness on a bus, or whether they would be afraid of someone exhibiting such signs.

Others indicate increased confidence in encounters with people showing signs of mental distress.

The study is a big deal, says Evans.

“You’ve got members of Congress pushing [Mental Health First Aid], the President pushing the idea, and states that have embraced it … but there’s not a lot of outcome research,” he says. “Do we have evidence that people who’ve taken the course have actually intervened, or gotten people into services?”

“Those answers are going to be really important to us, the city and really important to the field,” he says.

Meet the Principal Investigator

Nancy Epstein

With its emphasis on engaging marginalized communities and building community awareness and compassion around mental health issues, Mental Health First Aid poses a unique opportunity for Drexel Associate Professor Nancy Epstein, who has a decades-long history in health advocacy and public policy.

Epstein received a master of public health degree from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in 1980, and soon after became a grassroots community organizer helping tobacco farmers in North Carolina grow vegetables instead of tobacco and sell them at farmer’s markets and directly to restaurants.

She went on to work in public policy, and was subsequently appointed by Texas’ Governor and Lt. Governor to oversee the implementation of a public health care program for the indigent. She went on to Washington, D.C., where she was a consultant to the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and its grantees around the country before coming to Philadelphia 14 years ago to pursue what might seem like a very different path: rabbinical school, which she attended while teaching classes for Drexel’s School of Public Health. Eight years ago, Epstein was ordained a rabbi. She’s been a member of Drexel’s faculty for 14 years.