Known for its eclectic mix of tattoo parlors, street performers and surf shops, the bohemian Los Angeles neighborhood has long been home to the city’s younger creative and artistic crowds. But the boardwalk culture took on a new vibe after California became the first state to pass a medical marijuana law in 1996. Today, the strip is home to several pipe stores and marijuana dispensaries like The Venice Beach Care Center, Nile Collective and Green Cure Venice, where “budtenders” and “budistas” offer menus of buds for clientele carrying a California doctor’s recommendation for medical marijuana. Most sell a smorgasbord of marijuana-infused edible products like brownies and cookies, but also juices, olive oils and beef jerky infused with THC, marijuana’s mind-altering ingredient.

Drexel sociologist and School of Public Health Associate Professor Stephen Lankenau was living and working in Los Angeles in 2007 when the rapid growth in dispensaries — from four in 2005 to 186 two years later — motivated the city to impose a moratorium while it developed regulations. Entrepreneurs quickly took advantage of loopholes in the moratorium, which was never enforced, and over the next several years, the number of dispensaries in the city exploded — up to 1,000 by some estimates.

“They became as common as Starbucks,” Lankenau says.

Editor’s Note: In May, residents passed a bill calling for the closure of all dispensaries that had opened since the 2007 moratorium, which is intended to bring down the number of dispensaries to less than 140.

The number of medical conditions that qualify for marijuana treatment also exploded. Though the initial law focused on chronic health conditions like cancer and glaucoma, later changes permitted psychological conditions like insomnia and anxiety. According to one physician’s survey, California doctors have recommended medical marijuana for more than 215 conditions.

Lankenau knew the large number of medical marijuana dispensaries in the city and its diverse population of young adults made Los Angeles fertile ground for a scientific study.

“We started to see a lot of young adults getting recommendations for these conditions,” Lankenau recalls. “That should raise some red flags as to whether there might be some primarily recreational users mixed in with legitimate medical users. I wanted to look into that.”

An unstudied area

Lankenau recently got his wish.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health, has granted Lankenau $3.3 million over five years to conduct a study of medical marijuana use among young adults. Working with co-investigator Ellen Iverson at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Lankenau’s team will enroll 380 marijuana users this fall and expects to complete baseline interviews and surveys by early 2014. Half of the cohort will be qualified medical marijuana patients and half will be recreational users. Participants will complete annual follow-up interviews for three years.

It will be the country’s first large-scale federally funded case study of medical marijuana use among 18- to 26-year-olds.

NIH research grants — particularly the large and lucrative R01 grant type awarded to Lankenau — to study medical marijuana aren’t easy to come by. Possession and distribution of marijuana is still illegal under federal law, and despite supportive statements from President Obama, under his administration the Drug Enforcement Agency has stepped up raids of medical marijuana dispensaries in states where licensing guidelines are unclear.

A search of medical marijuana studies in NIH Reporter, the agency’s database of the research it funds, turns up just 15 active studies nationwide, and only about half of those deal with population behavior similar to Lankenau’s.

“It’s a controversial topic,” Lankenau says.

Lankenau’s interest in the relationship between medical marijuana and young people stems from his dissertation research on homeless panhandlers in Washington, D.C., where he saw firsthand how drug and alcohol problems affected the health of a vulnerable population. Later, as a postdoctoral fellow, he focused his work on substance use and HIV/AIDS.

“It became clear to me that substance use was at the heart of a whole range of social and public health problems — sometimes the cause and sometimes the effect — such as poverty, violence, disease, social justice, psychological and physical well-being,” he says. “Substance use is a very dynamic field for research.”

“What we’re really trying to find out is, is this a good policy for young adults? Does it seem to result in improved health overall, or does it have unintended consequences that may give pause to other states?”

– Stephen Lankenau

Most of the studies done on medical marijuana to date have focused solely on quantifying whether illegal marijuana use goes up or down in states after they pass medical marijuana legislation. Those studies have typically been smaller in scale, or involve secondary analysis of survey data without direct recruitment of medical marijuana-using subjects.

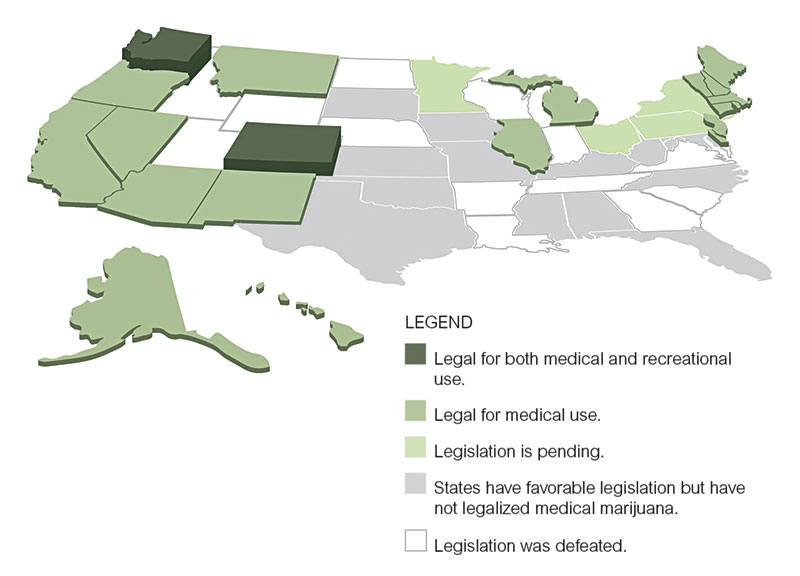

The federal stance on funding medical marijuana research has softened as the number of states that permit and regulate medical marijuana sales and use has continued to grow. So far, 20 states plus the District of Columbia have passed medical marijuana laws, and this past November, voters in Colorado and Washington (where marijuana for medical use was already legal) passed initiatives that legalized marijuana for recreational use. Bills that would allow medical marijuana are pending in four other states, including Pennsylvania.

See an Interactive Map Showing Medical Marijuana Legislation

Lighting Up by Law

Call it reefer madness, or call it the arrival of a sane public health policy at last—depending on your viewpoint. In 2013, lawmakers filed bills in 30 states and Washington, D.C., favorable to marijuana possession for personal or medical use. Two states, Illinois and New Hampshire, effectively legalized medical marijuana this year, bringing the total to 20 states and the nation’s capital where medical marijuana is legal. In addition, both Colorado and Washington passed laws legalizing recreational marijuana in last November’s election. Legislatures in four additional states, including Pennsylvania, are considering bills that would legalize medical marijuana.

The timing is ripe for more research.

Starting this fall, Lankenau’s team will recruit study participants by “hanging out” in areas like Venice Beach that have a large number of dispensaries. Participants receive $25 as an incentive to give the initial interview.

“It takes a little finesse and experience to do it in a way that makes the person comfortable talking about their drug use,” Lankenau says.

Lankenau’s collaborator, Ellen Iverson, says the age group targeted by the study is important because marijuana use (medical or illicit) typically peaks between ages 19 to 21.

“These often are the most vulnerable times of their lives — years when developmentally they are making significant, culturally adult-oriented decisions about their lives and their identities are very much in flux,” Iverson says. “There really hasn’t been a body of strong, rigorous evidence that looks at how young people make decisions about marijuana use. Here’s an opportunity to learn what kinds of issues they are using marijuana for and, especially as policy is being formulated and evolving, to understand how it affects [them].”

A better understanding of why young people turn to the drug could help better inform policies on medical marijuana, she says.

“What we’re really trying to find out is, is this a good policy for young adults?” Lankenau says. “Does it seem to result in improved health overall, or does it have unintended consequences that may give pause to other states? Or should it be scaled back somehow?”

Smoking out the facts

One hypothesis that Lankenau and his team want to test is the so-called “gateway theory” that marijuana users go on to use harder, more addictive drugs.

“It’s true that most people who use hard drugs like cocaine and heroin have used marijuana, [but] most people who have smoked marijuana don’t go on to use harder drugs,” Lankenau says. “There’s not really a lot of data that validates or supports that theory, but it’s sort of well out there in the popular imagination that one of the risks of marijuana is it can lead to harder drug use.”

In fact, Lankenau suspects the reverse may be true.

The idea that medical marijuana may potentially offer a protective effect against other drug use grew out of another large-scale study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse that he conducted at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. The study was focused on prescription drug abuse in young adults, but participants were asked if they used medical marijuana or smoked it recreationally. The team found generally lower rates of drug use overall with medical marijuana patients compared with recreational marijuana users.

A separate study along the same lines by a colleague in the Netherlands showed hard drug users were more likely to “step off” using those substances once marijuana use was decriminalized.

“It’s sort of turning the ‘gateway model’ on its head a little,”

Lankenau says.

Researchers will also seek to gauge whether young medical marijuana patients experience an overall improvement in physical and psychological health. Study participants will be asked a series of questions about the basis for their marijuana treatment recommendation and their medical history to discern whether they are, in fact, getting the prescription for legitimate purposes. They’ll also be asked about previously diagnosed conditions and what type of experience participants had using other drugs prescribed for it.

“Maybe they got a prescription for them, but those prescriptions didn’t seem to work the way they wanted or it didn’t result in the level of improved health that they desired,” Lankenau says. “Is [medical marijuana] effective in terms of improving physical or psychological health?”

A third component of the study will look at the dispensaries to see how they’re set up, how they service patients and what, if any, impact they have on emerging adults in their communities.

“Is there enough regulation? Are staff trained adequately to provide [health] information?” Lankenau says.

The findings on this issue could have the most impact for other states grappling with how to regulate the sale and distribution of medical marijuana. In Los Angeles, dispensaries became a lightning rod for controversy. When dispensaries started opening in neighborhoods across the city, residents blamed them for increased crime and noise. They pressured city officials to step up enforcement and shutter those that were operating illegally.

Since 2008, police conducting raids of illegal marijuana businesses have made more than 74 arrests citywide. More than $2 million in cash has been seized, as well as assault weapons, nine kilograms of cocaine, and large amounts of other illegal drugs, according to Los Angeles City Council member Mitchell Englander, a reserve police officer who also chairs the council’s public safety committee. In his 12th Council district, he’s worked with city administrators to shutter more than 60 dispensaries he says were operating illegally.

“I know firsthand about the crime and other negative impacts on our neighborhoods that the illegal storefront marijuana stores have had,” says Englander. “When California voters approved the Compassionate Use Act of 1996 legalizing medical marijuana, it is likely that they had clinics or pharmacies in mind, serving people with chronic debilitating illnesses, rather than the nearly 1,000 storefront marijuana stores that sprang up across Los Angeles.”

“Based on what we find, we could have recommendations on whether dispensaries are a good model for distribution,” says Lankenau.

A patchwork of policies

Across the country, thousands of licensed physicians have recommended medical marijuana to at least 600,000 patients in states with medical marijuana laws, and the rate of legalization has outpaced policymakers’ grasp of the long-term consequences of widespread availability of marijuana.

The emergence of marijuana into mainstream medical usage traces back to 1982 when the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine confirmed the “therapeutic potential” of marijuana. More recently, 76 percent of 1,446 physicians polled in the New England Journal of Medicine said they would prescribe marijuana to treat pain from cancer. And in August, influential CNN chief medical correspondent Sanjay Gupta, MD, reversed his long-held position on the issue, concluding, “Sometimes marijuana is the only thing that works.”

California became the first state to sanction medical marijuana use when voters adopted the Compassionate Use Act of 1996. Since then, the state and localities there and in other states have struggled to balance the desire of patients to have safe, easy access to the drug with a public safety interest in curbing potential exploitation of the system by recreational users or criminals. In the latest development, California’s Supreme Court held in May that dispensaries were legal but could be banned by local governments.

“There really hasn’t been a body of strong, rigorous evidence that looks at how young people make decisions about marijuana use. Here’s an opportunity to learn what kinds of issues are they using marijuana for and, especially as policy is being formulated and evolving, to understand how it affects [them].”

— Ellen Iverson

More than 3,000 miles away from Venice Beach in New Jersey, the issue isn’t whether there are too many dispensaries, but whether the state should loosen its restrictive medical marijuana law to make it easier for more dispensaries to open. New Jersey permitted the sale and use of a limited number of strains of medical marijuana three years ago, but so far only one dispensary has opened.

Other states are trying to find the middle ground between the approaches taken in California and New Jersey. In Illinois, the most recent state to pass medical marijuana legislation, the bill’s chief architect and backer, Democratic Rep. Lou Lang, boasted at a bill signing ceremony that the law was “the most controlled and highly regulated bill in the country.” Illinois limits the number of cultivation centers to 22 and only allows for 60 dispensaries across the state, but it’s unclear how those numbers were selected.

In August, Attorney General Eric Holder announced that the Department of Justice would not seek to prosecute individual users and those who work in the industry in states that have legalized the drug for personal or medical use as long as states “implement strong and effective regulatory and enforcement systems” — a signal that the federal stance is softening further, but also a warning that the DOJ reserves the right to intervene if states don’t go far enough to protect public health and safety.

“It’s an emerging trend around the country to pass this kind of law,” Lankenau says. “We hope the findings from our study may help inform other policies around the country as to whether this is a wise policy or whether it’s something that should be given further consideration.”

A long, strange trip

Timeline of recent medical marijuana laws in Los Angeles and California

1992

— Medical marijuana is approved in a few California cities including Santa Cruz.

1996

— California voters pass Proposition 215 (the Compassionate Use Act), which allows medical marijuana to be dispensed to patients with a doctor’s recommendation.

2003

— Senate Bill 420 (the Medical Marijuana Program Act) is written into law to clarify the scope and application of the Compassionate Use Act of 1996. It paves the way for a voluntary statewide medical marijuana identification card program.

2005

— Los Angeles has four known marijuana dispensaries, in Hancock Park, Van Nuys, Rancho Park and Cheviot Hills.

2007

— Concerned by a 2,350 percent increase in the number of medical marijuana dispensaries in Los Angeles during an approximately one-year period, the City Council establishes a moratorium on new medical marijuana storefronts on Aug. 1 and places restrictions on hours of operation and their proximity to schools, churches, parks and other dispensaries.

2008

— California Attorney General Jerry Brown issues a directive of guidelines for medical marijuana cooperatives including that they sell only to legitimate patients, operate as nonprofits, and only buy [marijuana] from fellow cooperative members.

2009 —

Federal officials announce that they will no longer try to block medical marijuana distribution and use in California.

January 2010 —

The Los Angeles City Council, without debate, approves an ordinance to shut down hundreds of medical marijuana dispensaries and impose strict rules on the operation and locations of cannabis clubs, shops and collectives. The ordinance caps the number of dispensaries at 70 (with the exception of those registered with the city in 2007).

2012 —

The Los Angeles City Council banned all marijuana dispensaries, only to repeal the ban amid opposition.

May 6, 2013 — The California Supreme Court rules that local governments can ban marijuana dispensaries, the Los Angeles Times reports.

May 21, 2013

— By a margin of nearly 63 percent, Los Angeles voters pass Proposition D, which aims to cap medical marijuana dispensaries to 135, forcing more than 1,000 shops that don’t meet the new legal qualifications to close.

Source: Timeline reprinted with permission from Shana Ting Lipton, About.com (exception: the May 6 entry was sourced from the Los Angeles Times).