Photos by Jeff Fusco

Stacey Swigart and Michael Shepherd, director and assistant director respectively of the Atwater Kent Collection, have spent the past year packing, unpacking, and repackaging urban mementos to make them accessible to Philly history fans.

Inside a storage suite of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Stacey Swigart punches the name Cavada into a database she’s building for the Atwater Kent Collection, and — presto! — a little-known morsel of Philadelphia history pops onto her screen.

It’s an image of a painting. In the 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, Cuban American artist Ferderico Fernández Cavada depicted a smoke-filled Civil War battle scene of Union troops on the move. Turns out, Cavada was a civil engineer and illustrator who lived on Spruce Street and attended Central High School. During the war, he went up in hot-air balloons to sketch enemy positions, and even wrote a book about his time as a Confederate prisoner. He later joined the Cuban independence fight but was killed by firing squad in 1871 as a rebel.

“I’d never heard of this guy,” Swigart says. “This is an amazing Philadelphia story without being a Founding Fathers story. These are the things that give me goosebumps.”

Such are the curiosities in the Atwater Kent Collection (AKC), a trove of Philadelphia-centric relics that had until recently been packed away in a warehouse in East Falls. Drexel pledged to steward the collection in 2019 and brought it to PAFA last year, naming Swigart director and charging her with making the collection accessible to the city once again.

She and colleagues have spent the past year and a half ensuring each piece is carefully preserved, catalogued, photographed and organized so they can reintroduce the assemblage to the public through exhibits, careful loans, and through Swigart’s database, which went live in February at philadelphiahistory.org.

All told, the Atwater Kent is 130,000 pieces of memorabilia, artifacts, documents, furniture and garments from 300 years of Philadelphia’s history, industry and families. It was established by Philadelphia radio manufacturer A. Atwater Kent Sr. in 1938 when he donated a building at 15 S. 7th Street for the creation of a Philadelphia History Museum.

On May 10, 2022, the Orphan’s Court cleared a path for Drexel to eventually become permanent trustee of the collection.

Here’s the brief backstory of how Drexel came to be the collection’s steward: Five years ago, after struggling with waning visitors for many years, the Philadelphia History Museum closed its doors. For a while, its collection appeared to teeter on the verge of being sold off in bits and pieces. When no other institution stepped forward, Drexel volunteered to keep the Atwater Kent Collection (AKC) intact and to preserve and protect its record of the history of Philadelphia’s many communities and peoples such as Cavada.

“It is one of the few collections where Philadelphians can see their experiences, their neighborhoods and their traditions reflected,” says Kelly Lee, Philadelphia’s chief cultural officer and director of its Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy. “This collection must remain in Philadelphia.”

Many at Drexel, with President John Fry leading the way, realized early on what was at stake, says Rosalind Remer, senior vice provost for collections and exhibitions and executive director of the University’s Lenfest Center for Cultural Partnerships. “The collection would get scattered to the four winds if the museum closed and no one managed it,” she says. “You will never be able to put that back together again. It’s like Humpty-Dumpty.”

AKC is a great match for Drexel’s tradition of accessible art and hands-on education, Remer says. In the works is a loan program to libraries and schools, and the collection’s management offers experiential learning opportunities for future art program graduates. Already, the digital database has been incorporated into courses, projects and extracurriculars, with more planned.

“Because the collection is so varied,” Remer says, “there is almost no class that couldn’t use something.”

Museums are increasingly focused on storytelling rather than the intrinsic value of an item, notes Derek Gillman, executive director of University collections and exhibitions and Drexel’s distinguished teaching professor of art history and museum leadership. “With Atwater Kent,” Gillman says, “there are literally hundreds of thousands of stories that can be attached to these objects.”

Certain high-profile pieces tend to get all of the attention. A certain president’s desk. Another’s hat. Some prized boxing gloves. But the bulk is everyday stuff, a mish-mash that has earned AKC the moniker “Philadelphia’s Attic.” Stacked upon shelves within the PAFA storeroom where the collection is now kept are vacuum cleaners, glass medicine bottles, tools from the now-defunct Disston Saw Works in Tacony, hats from the once Kensington-based Stetson Hat Factory (but no cowboy ones, alas), weights and measures, candy boxes, street lights, roller skates, handkerchiefs, shoehorns, grandfather clocks, and more. Lots more.

“We even have the kitchen sink,” Swigart says. “It’s a miniature dollhouse fixture.”

Each piece has a story to tell about the city. And, for the first time in years, the collection is speaking again.

Over the summer, visitors glimpsed AKC artifacts in the first public exhibit organized by Drexel, at PAFA. “Seeing Philadelphia” juxtaposed old and new perspectives on city life, showing different views of Philadelphia over the generations. Archival prints, drawings, photographs, paintings and maps were displayed alongside new contemporary pieces created by members of Drexel’s Writers Room, a storytelling program in which students and non-students collaborate creatively.

Next July, a larger viewing will be on display when PAFA hosts “Philadelphia Revealed: Unpacking the Attic.” Many pieces from the AKC also will be on loan to museums across the city during the celebration of Philadelphia’s 250 years starting in 2025.

Major cities the world over have museums dedicated to telling their stories, points out Paul Steinke, executive director of the nonprofit Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. “Atwater Kent was — and hopefully will be again — our answer to that, a way to tell Philadelphia’s compelling story to its own people but also the state, the nation and the world,” he says. “It should be a priority.”

That future depends on Drexel now, and Steinke, for one, is optimistic. “Critics will say that you’re taking something that the public owns and putting it into the hands of a private institution,” he says. “But Drexel has time and time again shown that it has the wellbeing of Philadelphia’s civic interest at heart of everything it has done with the collection to date.”

“I’d never heard of this guy,” Swigart says. “This is an amazing Philadelphia story without being a Founding Fathers story. These are the things that give me goosebumps.”

From the Collection

With a glass and metal picture tube, this 1959 Philco Predicta Siesta television was marketed, along with other Philco Predictas, as the world’s first swivel-screen TV set. Philco, an American electronics manufacturer headquartered in Philadelphia, was a pioneer in battery, radio and television production. This television was designed by Catherine Winkler, Severin Jonnaffen and Richard Whipple.

When it was first founded, the Philadelphia History Museum bought or accepted loans of historical items regardless of where they were from, says Swigart. “It wasn’t necessarily Philadelphia history; it was history,” she says, noting that some of the earliest pieces acquired were produced by artists sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. Over time, the museum began absorbing materials from other local institutions that shuttered or whittled their holdings.

Gradually, the Atwater Kent Collection became caretaker to many of the city’s orphaned artifacts. For instance, from the Charles Willson Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, considered the first public museum in the country, it has about 30 Peale family paintings. Swigart ticks off others that surrendered their accessions to the AKC: Long’s Museum and Varieties. The Police Historical Society. The Commercial Museum/Civic Center Museum. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The CIGNA Collection.

It became, Swigart says, “a collection of collections.”

But over the years, the museum struggled. Despite its vast mix, it only exhibited a small portion. It fell into arrears as attendance dropped to just 10,000 a year on average. When the museum closed its doors in 2018, just 276 items were on display.

The following year, Drexel began talks with the city to steward the AKC. By fall 2019, a transfer plan was approved that included a five-year, $1.5 million contract to inventory and evaluate the collection. The University was granted oversight in April 2022.

Later that year, 101 truckloads transported the collection to PAFA, where Drexel is leasing 11,000 square feet of climate-controlled storage space. The largest items, too big to bring into the academy, are stored offsite. One is the very first Atwater Kent acquisition: a 6-foot-long scale model of Elfreth’s Alley constructed by artists during the Depression.

Meanwhile, Melissa Clemmer, associate director at the Lenfest Center, went to work applying for grants to support digitization, exhibits and other programs.

So far, Drexel has won about 15 public and private grants, including from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Archives, totaling more than $1.85 million. Most recently, the Pew Charitable Trusts contributed a $850,000 grant to support conservation, digitalization and a community lending program.

“The more we’re able to raise,” Clemmer says, “the more we can do to get the collection out of storage and into the community.”

One priority is to restore the collection to the public for research and learning. A 2020 Colonial Academic Alliance grant supported two Drexel graduate students with degrees in arts administration and museum leadership — Jasmine Mathis, MS ’21 and Caleb Craig MS ’21 — in developing a school program that incorporates African American artifacts as a vehicle to discuss race, identity and negative stereotypes. Craig, a banjo player, focused on a “Plantation Banjo Chant” music sheet promoting a popular minstrel as a starting point to discuss the harmful consequences of blackface. Mathis used dolls depicting African American Quakers as part of a unit on citizenship and “American” attributes.

Drexel also has collaborated with the University of Delaware’s Center for Material Culture Studies on a toolkit focused on using historical collections for innovative teaching. Craig, 32, of Vestal, New York, says the 50-page report documents evidence-based best practices for “different styles of learning that can be utilized to uplift voices typically not looked at or ignored.”

Drexel’s track record of building and overseeing collections goes back to its very first days. One of the earliest acts of the University’s first president, James A. MacAlister, was to establish a museum to complement the study of materials and textiles, now part of Drexel’s Founding Collection. MacAlister used $1 million from founder Anthony J. Drexel to acquire objects overseas such as redware bowls from Pakistan, wall tiles from Turkey and a copper ewer from Antwerp. The University maintains six other collections, including the Robert and Penny Fox Historic Costume Collection, the Polish Poster Collection and specimens within the Academy of Natural Sciences.

“We collect,” says Gillman, who before coming to Drexel had a nearly 30-year career in art museum leadership on three continents, including having served as president and director of PAFA and executive director and president of the Barnes Foundation, where he oversaw the relocation of the collection from Lower Merion to Center City. “We’ve been collecting for 130 years.”

“It is one of the few collections where Philadelphians can see their experiences, their neighborhoods and their traditions reflected,” says Kelly Lee, Philadelphia’s chief cultural officer and director of its Office of Arts, Culture and the Creative Economy.

From the Collection

This 20th-century, well-used blue newsboy bench with yellow lettering was a gift to the Philadelphia History Museum from David Rasner, whose grandparents ran a newsstand in a building on Arch Street near the Center for Architecture and Design (AIA Philadelphia). For many years, the Philadelphia Bulletin, an evening daily newspaper published from 1847 to 1982, enjoyed the highest circulation rates in the city.

In PAFA’s storeroom, among labeled metal shelves packed with nostalgia, Michael Shepherd is photographing a Wanamaker sewing machine from the left, right, behind and above. He captures a model number and some scrollwork that he anticipates researchers might find interesting when they search the database portal.

“Any kind of detail you might think of,” says Shepherd. “I love the every day.”

As the collection’s assistant director, he has put in many hours documenting objects. He dwelled on the collection’s paintings, zooming in on handwritten notes in pencil on the backs that are easy to overlook. His favorite find is a 19th-century deck of cards. On the back of a Joker is a tally in pencil of the winnings accrued by a mom, uncle and son.

“Anything that tells a story,” he adds, echoing Swigart.

A double Dragon, Shepherd returned to college as an adult in his 30s after studying architecture and photography, when he realized that what he really loves is handling old objects, especially vintage photos. He enrolled for history (2014) and library and information science, with a concentration in archival studies and digital curation (2018) and did his co-op with Drexel’s Fox Historic Costume Collection. That led to a job with the costume collection, which led to the Atwater Kent.

He’s living his dream job, he says. He grew up in Upper Darby and loves city history. “I wrote about Philadelphia as an undergraduate so much that my thesis adviser said I needed to write about something else,” he says, smiling. He believes Philadelphians treasure history told through daily life.

“We’ve all seen the Liberty Bell 15,000 times,” he says. “But if you talk about the building in your neighborhood that used to be a movie theater, people’s faces light up. They want to tell you what they know about it. It’s a very hyper-local sense of history here.”

“We’ve all seen the Liberty Bell 15,000 times,” he says. “But if you talk about the building in your neighborhood that used to be a movie theater, people’s faces light up.”

From the Collection

This 1932 cathedral-style Radio Model 84 Super Heterodyne was manufactured by the company founded by A. Atwater Kent Sr., which was the largest producer of radios in the world in the late 1920s. The back is uncovered, revealing the inner workings and multiple tubes.

From the Collection

This incredibly detailed — there’s even a tiny working garden gate — miniature of Elfreth’s Alley, Philadelphia’s most famous historical block, was created during the Great Depression by out-of-work artists. The six-foot diorama was the first item acquired by the Philadelphia History Museum.

In June, Drexel organized its first Atwater Kent Collection public exhibit. “Seeing Philadelphia” juxtaposed historical images of the city with contemporary pieces created by students and community members who belong to the Drexel’s Writers Room. A larger exhibit is being planned for next July.

Swigart agrees. She loved to visit PHM as a kid, obsessed with dolls and miniatures; these days, it’s hard for her to pick a favorite object. Near the top, though, is Young’s Candies and its tools of the trade, including ice cream scoops, dishes and candy molds.

“It’s wonderful,” she says of the 110-year-old business that closed in 2007. “They designed this particular chocolate bunny. People would line up to get it at Easter.”

Preserving these histories stokes her passion for her work, she says, and keeps her going through the more mundane aspects. Early on, Swigart was tasked with dismantling PHM, down to the exhibit cases and office furniture, along with Page Talbott, the Lenfest Center’s director of museum outreach and AKC project evaluator. The two women spent hours organizing and evaluating the warehouse’s contents — when not dealing with the building’s leaky roofs and toilets.

Talbott, with assistance from Swigart, has the herculean task of determining the strength of each item’s connection to Philadelphia on a one to four scale, four representing no connection. So far, all 37,000 objects have been evaluated and assigned to one or more of the 44 categories (say Ceramics and Glass or Numismatic or Toys) that Talbott and Swigart devised as part of the taxonomy of the portal. Objects also are tagged with keywords. Each month they add about 100 items, including pictures and short descriptions, to the portal. (The same process is under way for the 45,000 items in archives.)

“It’s tedious,” Talbott allows, but adds it’s essential to making the collection accessible. Consider a dividend check announcement card from the Union Traction Company, which controlled the trolley system in Philadelphia.

Talbott, with assistance from Swigart, has the herculean task of determining the strength of each item’s connection to Philadelphia on a one to four scale.

From the Collection

This circa 1920, oval-shaped paper hatbox was produced by the John B. Stetson Company on Germantown Avenue. It was the largest hat factory in the world at the time. A size chart on the side of the box has a pencil mark at 7 1/8, and on the bottom of the box is an inscription. The hatbox was a gift of Helen M. Beitler to the Atwater Kent Museum.

“You’re yawning,” she half jokes. But for those interested in this bit of history, Talbott says, the tags make the difference. “You might tag it as Union Traction Company or as trolley or as situated on Dawson Street or as dividend. You have to think, ‘What are people going to put in a search bar?’”

The painstakingly curated portal officially went live Feb. 14 with 1,212 items, including a stash of AKC historic Valentine’s.

“That was our love letter to Philly,” Swigart says. “It’s still a work in progress. There are a million and one things.”

She tracks her progress and any problems by writing notes in journals ringed with numerous color tabs sticking out. She’s already filled 12 journals.

Clearly, all that work is paying dividends. Since the portal launched, the searchable items have grown to 3,406 as of early September, with a target of 7,000 objects within the next several years. Through the end of August, the portal was used 15,227 times, with the random image generator a popular option. Common keyword searches include Franklin, radio, Rocky and wampum, among others.

“It’s a museum without walls,” Remer says with a measure of pride. “There are more items online than there ever were on display.”

“We even have the kitchen sink. It’s a miniature dollhouse fixture.”

– Stacey Swigart

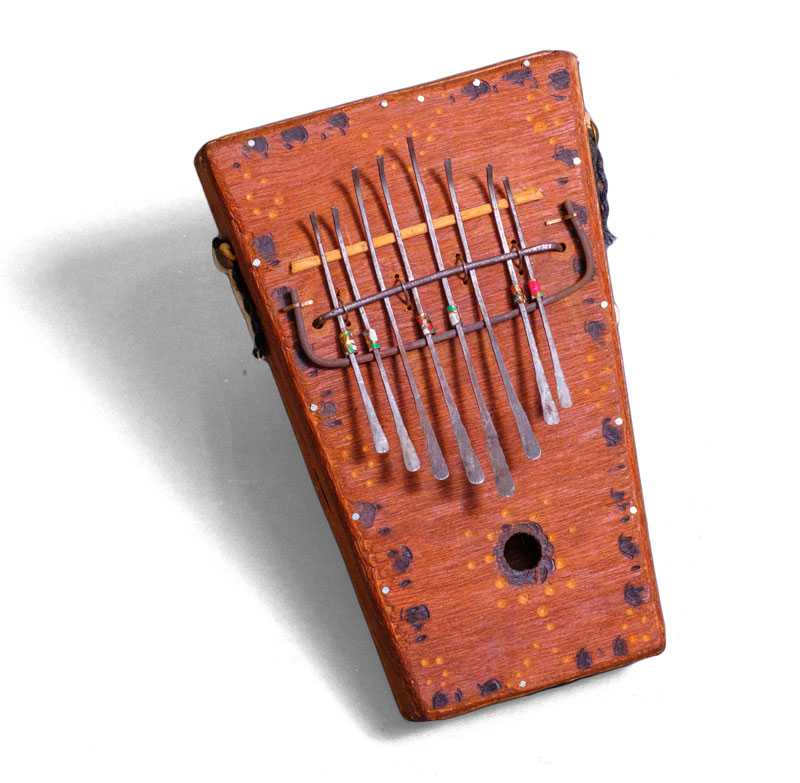

From the Collection

This 1980s plywood thumb piano, decorated with a dot pattern of indentations, has eight bent metal keys that are plucked with thumbs and are decorated with beads of painted metal. Carved into one end are the initials “AK” — the signature of African American instrument maker and street artist Adimu Kuumba (1952–2021), who lived at the time of the gift on Bernard Street in Philadelphia. This object came to the collection from the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies.

On this summer evening, the vibe at PAFA’s Francis M. Maguire Gallery is electric as “Seeing Philadelphia” celebrates its opening — and the first public debut of Drexel’s stewardship of the Atwater Kent Collection.

Eric Pryor, PAFA’s president and CEO, praises the “great strategic alliance” between the University and the academy. The city’s Lee says the show is “an example of how Drexel will use this collection to continue to tell the story of Philadelphia for generations to come.” And Youngmoo Kim, vice provost for university and community partnerships, notes that Drexel “strives to be the most civically engaged university in the country, and through innovative partnerships and programs like this exhibit, we’re able to pursue this goal.”

Twenty-three-year-old Kat Odoms ’23, an English major, mingles with friends. She is one of the people who contributed some of the contemporary images to the show through her participation in an intergenerational storytelling initiative organized by Drexel’s Writers Room.

“The city,” she says, “is constantly changing from within and without.”

One of Odoms’ three photographs is a head-on shot of the Le Meridien Hotel at 1421 Broad St. It is juxtaposed with Benjamin Ridgway Evans’ 1831 pen-and-ink and watercolor depiction of the elegant Indian Queen Hotel at 15 S. 4th St., since demolished, and McLintock’s (first name unknown) 1940 WPA photo of the same address showing a row of jammed-together businesses.

She picked the hotel because it used to house the YMCA where her mother worked and where she often visited as a child. Odoms, who has plans to work in community organizing, credits the Writers Room’s TRIPOD program — and access to AKC photos and etchings, a first for the program — with broadening her view of the city she loves and how old neighborhoods have evolved and redeveloped.

“I really wanted to speak on how can we keep that history and not erase it, but also make room for new things and new growth,” she says.

That’s exactly the type of critical thinking and contextualizing experience that Drexel expects the collection to help imbue.

“This is a glimpse,” Remer says to the crowd. “The exhibition you see here is what I like to look at as a down payment on future programs and exhibitions.”

Swigart, standing nearby, beams, and along with all the others, offers her hearty applause.

“That was our love letter to Philly.”

– Stacey Swigart, on a stash of AKC historic Valentine’s included in the collection