Ron Hoppes ’60 first saw the David Rittenhouse Astronomical Musical Clock on his way to class. “I used to shimmy past that clock and look up at the dial and say ‘Boy, look at that,’ never thinking I’d ever get to be that closely associated with the clock,” he says. In those days, Hoppes was an electrical engineering student. He didn’t know that within three years of graduation, he’d buy a clock and fi x it himself — and then put his engineering talents to use as a clock conservator, which is how his path eventually led him back to Drexel, straight to that remarkable clock. Hoppes is one of nine professional outside conservators — including experts in furniture, paintings and frames, sculptures and metals, and paper — currently working with the University to restore, catalog and showcase the University’s art collection.

1

TITLE

Tall Case Astronomical Musical Clock

ARTIST

Rittenhouse, David

DATE

c. 1773

PLACE OF ORIGIN

United States, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

MEDIUM

Mahogany, white cedar, poplar, oak

DIMENSIONS

112×29 3/4×17 1/4 in

In addition to the famed 1Rittenhouse Clock, The Drexel Collection encompasses more than 6,000 artifacts, artwork and objects housed across campus.

Drexel founder Anthony J. Drexel began amassing The Drexel Collection in 1890, building on the paintings belonging to his artist father with additional artwork and objects purchased on a legendary shopping expedition by the University’s first president.

A.J. Drexel’s desire was to inspire an appreciation of art in the largely working-class students attending his new school, both to enrich them personally and to expand their understanding of industrial design. He housed Drexel’s collection in a museum in the midst of his classrooms, on the ground floor of the Main Building.

“The early pieces were very eclectic,” says Lynn C. Clouser, director of The Drexel Collection. “It was a hodgepodge collection meant to show different techniques and designs that were being used at the time.”

These were not objects to be set away on protected plinths. They were to be handled and exhibited, discussed and displayed. Naturally, that legacy presents some unique challenges for modern-day conservators.

A Little TLC

When A.J. Drexel asked Drexel’s first president, James MacAlister, to travel to Europe and spend $1 million ($25-plus million today) on more than 200 artifacts and materials for the collection, his instructions were to find historical and contemporary pieces that could be used to show students how items were made.

2

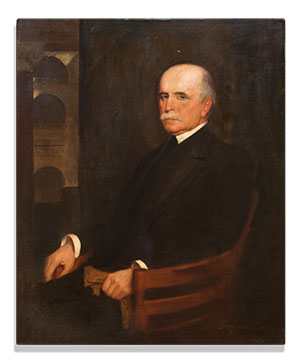

TITLE

Portrait of Anthony J. Drexel (1826-1902)

ARTIST

Constant, Jean Joseph Benjamin

DATE

1894

PLACE OF ORIGIN

United States

MEDIUM

Oil, canvas

DIMENSIONS

45×35 in

Over subsequent generations, those original holdings expanded almost at random. To A.J. Drexel’s initial endowment of objects were added the art collections of his brother-in-law John D. Lankenau and friend and business partner George W. Childs. The trio also asked family and friends to donate. Donors and alumni have bequeathed new acquisitions to the collection since.

Not all of the collection’s items were treated with the care they should have gotten at that time — and others were donated to the school already damaged. Combined with storage spaces that weren’t built to protect furniture and art, and the collection suffered.

That started to change in 2011, when Drexel mounted an effort to conserve and properly catalog the collection. Drexel first expanded and renovated the collection’s storage area by upgrading its HVAC system and blocking windows.

“We cleaned up the space so we knew what we had,” says Clouser, who recalls hearing stories of objects stored in old china cabinets and corner cupboards. “The new storage area is beautiful; it’s well organized, objects have a home for the fi rst time. Having worked in other collections, I was really impressed for a university to have a storage space of this grade; this was on par with more standalone museum storage.”

3

TITLE

Celestial and terrestrial library globes

ARTIST

Charles Smith and Son

DATE

c. 1870

PLACE OF ORIGIN

England

MEDIUM

Papier-maché, plaster, mahogany, brass

DIMENSIONS

18 in

For the first time, Drexel had a complete catalog of what items had been lent out to offices and buildings across the University — an effort that turned up some forgotten pieces. Clouser discovered a 2lost portrait of A.J. Drexel sitting in a closet, for example.

So far, more than 65 items that were delicate, damaged, dirty or a combination of all three have been conserved. Over the past six years, the University has invested more than $250,000 toward the effort.

Among the items saved from a century of deterioration were 3two late 19th-century globes created by Charles Smith and Son. They were fabricated from plaster and papier-mâché spheres covered with paper on which the designs were intaglio printed and colored by hand. Both globes had damage to their structures and surfaces designs and were missing compass dials and glass.

Paper conservator T.K. McClintock of Studio TKM in Somerville, Massachusetts, undertook their careful restoration over a period of 13 months.

“The sphere obviously needed to be repaired where it was broken, and to do that, you have to first take off the discolored varnish,” says McClintock.

He then removed the paper from the spheres where they were damaged, which was conserved separately while he repaired the damaged underlying plaster. Where pieces of the paper were missing, he identified identical globes in other collections and recreated matching sections using digital images and lithographic printing. Where there was staining of the paper and loss of the hand-applied color from water damage, he reduced the discoloration and in-painted the missing background color.

Modern conservation is directed toward improving legibility and condition, and all procedures and materials are intended to be reversible. That wasn’t always the case.

4

TITLE

Isle of Sylt

ARTIST

Dücker, Eugène Gustav

DATE

1879

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Germany

MEDIUM

Oil, canvas

DIMENSIONS

22 1/4×37 3/4 in

“The big thing today is stability and reversibility,” says Aella Diamantopoulos, a painting and frame conservator who works with Drexel. “Any sort of intervention you have with a painting, you want to minimize. This is something that you do every 80 to 100 years. You don’t want to be cleaning a painting over and over again.”

Modern-day conservators are constantly correcting and reversing poorly executed older techniques that were at one time considered standard practice.

“Fifty years ago, conservators were a little more heavy handed than they are today,” Diamantopoulos says. “When you retouch losses today, you stay within the areas of loss, whereas in the past they were a little bit more liberal about going over the original.”

Diamantopoulos has been working with Drexel since 2012 and has conserved about 50 paintings,frames included.

One of her favorites is a painting by German painter Eugène Gustav Dücker called 4“Isle of Sylt.” The canvas was so dirty that observers initially thought the painting depicted a stormy beach. Beneath the grime and age, a shape on the sand that had previously appeared to be storm-battered driftwood turned out to be a person lounging in the sunshine of a pleasant day.

5

TITLE

Conical Clock

ARTIST

Albert Ernest Carrier-Belleuse and Eugene Farcot

DATE

c. 1867

PLACE OF ORIGIN

France

MEDIUM

Silver, brass, marble

DIMENSIONS

60x30x27 in

Possibly the most valuable and significant pieces of the collection are its clocks, most of them donated in 1894 by the widow of Childs, who was the publisher of a prominent Philadelphia paper and A.J. Drexel’s lifelong close friend. This gift included the David Rittenhouse Astronomical Musical Clock, which Hoppes passed on his way to class in the late 1950s.

“It was the most complicated clock he ever constructed,” said Hoppes of the astronomer Rittenhouse.

The clock tells time, month and day, location of planets, tracks astronomical phenomena and plays 10 different tunes. It also shows locations of zodiac constellations. The 1773 piece was appraised for $10 million, and in 2009, Hoppes wrote a book about it titled, “The Most Important Clock in America.”

He also played a role in restoring an 5 1867 Eugene Farcot Conical Clock located in the lobby of the Main Building, which was also given to the University by the Childs family.

“When I went to school, it never had a pendulum,” recalls Hoppes. The pendulum had been removed and stored underneath a bench in the collection’s storage area. “It was all bent and smashed. It looked like some disgruntled student hit it with a baseball bat,” Hoppes says.

Now working, conserved — and with a straight pendulum — the clock is one of the most recognizable sights in the Main Building.

6

TITLE

Urn

ARTIST

Saxon Porcelain Manufactory

DATE

late 19th century

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Germany, Potschappel

MEDIUM

Hard-paste porcelain, lime glaze, polychrome

enamels, gilding

DIMENSIONS

28 1/4 x 11 1/2 in

Practical Arts

But filling the University with illustrious décor isn’t the purpose of this conservation, says Clouser: “It’s to make the collection a teaching tool again.”

One reason that’s a possibility is because there are no Picassos in need of protection. While the collection includes some big-ticket pieces, most are more historically significant than monetarily significant. “There’s less fear of things being damaged,” she says.

That’s a plus when classes want to incorporate pieces from the collection into their lesson plans.

In this regard, Clouser herself is a bit of a treasure. She trained in art conservation as an undergraduate and has a master’s in museum studies from Georgetown University. Through internships, fellowships and employment, she has experience in conservation, collection management and registration with a range of prestigious regional institutions: Hagley Museum, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, the Barnes Foundation and Winterthur Museum.

7

TITLE

Ancient coins

ARTIST

Unknown

DATE

c. 300 BCE – 300 CE

PLACE OF ORIGIN

various

MEDIUM

Silver, bronze

Clouser frequently takes students on tours of the collection or hosts art-related workshops for classes.

For example, The Drexel Collection contains an example of a 6war-era Dresden urn that is sometimes used to help students in an English 103 class on war literature appreciate Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five.” When students reach the chapter in which the main character uncovers a Dresden teapot among the city’s ruins, Clouser presents a brief history of ceramics and displays the Dresden urn to convey the beauty among the rubble that Vonnegut was trying to express.

In an English 101 class called “Self-Representation in the Digital Age,” Clouser provides an art history lesson on how symbols are used in self-portraits, such as the use of books and jewelry to convey status. She introduces collection pieces ranging from 7ancient Roman coins to the Drexel family portrait to demonstrate the range of materials used in portraiture.

As a final project for the class, the students created self-portraits for a public campus exhibition on April 14 that showed what they had learned, often with amusing modern interpretations. One student, Michael Barsoum (materials engineering ’21), used 18th-century portrait styles to satirically depict a typical millennial man: Inside an Old World gilt frame, a young man poses with a Red Bull and a cell phone, amid other symbols of his generation.

8

TITLE

Miniatures

ARTIST

Unknown

DATE

early 20th century

PLACE OF ORIGIN

unknown

MEDIUM

Mixed media

DIMENSIONS

very tiny, like palm-sized

In conjunction with the self-portrait exhibit, art history students built a sister exhibit that was “progressively curated,” meaning students gradually added layers of new information onto the exhibit each week. At first, the objects — a selection of artworks, prints, sculpture, ceramics, metals, glass, etc. — were presented with no information. Over the course of a term, as students researched the pieces, they added new details about historical context, technique, artist and function.

Visitors to Rincliffe Gallery were able to watch the exhibit unfold in real time as the aspiring curators studied the artifacts at progressively deeper and deeper levels.

Every couple of years, students who aspire to museum careers completely take over Clouser’s role and produce their own exhibit. In 2015, they combined some of the 8tiny furniture and children’s toys in the collection with other curated artifacts to create an exhibit illustrating the evolution of toys and notions of childhood. Students were responsible both for curating and for the physical layout of the gallery and all of the labels and signage. This winter, students from the course will produce an exhibit called 9“drinkware at Drexel.”

9

TITLE

Venetian Wine Glass with Drexel Family Crest

ARTIST

unknown

DATE

19th century

PLACE OF ORIGIN

Italy

MEDIUM

Soda glass, gilding, blown

DIMENSIONS

3×8 in

Each group of students undergoes training to learn how to handle the delicate pieces. “I wear gloves for metals; clean dry hands for everything else,” says Clouser. “Gloves can remove some tactile sensation and accidently tear something. I wouldn’t wear gloves when handling paper, or with glass or ceramics, because they are slippery and you can drop them.”

Another lesson: Never pick something up by its handle; you never know when something has an unseen crack or old repair.

That’s the kind of literally hands-on interaction that the founder and first president foresaw when they began building the collection 125 years ago.

Writing in the “Catalogue of the Picture Gallery” in 1897, Drexel President James MacAlister expressed his hopes for the collection’s role:

“Any real knowledge of and feeling for art in its many aspects can only be acquired by direct contact with the various forms in which it is embodied. We can learn a good deal from reproductions and books, but the feeling for beauty and the refined enjoyment which works of art are capable of yielding, are only possible in the truest sense by living in their presence and becoming familiar with them as we do with a fine poem or some lovely aspect of nature.”