The Army Specialized Training Program curriculum mandated several hours of physical education each week. Cadets trained at the athletic fields at 46th and Haverford. Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The United States’ entry into World War II heralded a massive expansion of the Armed Forces and panic in the halls of higher education, which fell quiet as the nation marched to war. In the first year of the war, college enrollments nearly halved, dropping from 1 million to 600,000. Some college administrators worried they would have to temporarily close their doors, and government officials fretted that if the conflict was long-lasting, the military would find itself in need of soldiers with technical training that the Army could not provide.

The government solved this dilemma with a plan to train the brightest soldiers at the nation’s colleges in subjects with military applications like engineering, medicine and foreign languages. The Army Specialized Training Program (“ASTP”), as it was known, would both breed brainy soldiers and save struggling institutions like Drexel, known in those days as the Drexel Institute of Technology.

The Army, however, was never very committed to the idea of providing higher education to soldiers, regardless of their academic abilities, when it was fighting an unrelenting global war. While there may have been a benefit in specialized training, their keenest need was for combat troops — and there was already a shortage of those. On the eve of the ASTP’s introduction, the commander of the Army’s Ground Forces, General Lesley McNair, bemoaned that “with 300,000 men short . . . we are asked to send men to college!”

McNair’s protests went nowhere, but as Drexel’s brief history with the ASTP experiment showed, his concerns were prophetic.

“The standards of Drexel are very high”

On July 13, 1943, the 3318th A.S.T.U. (Army Specialized Training Unit) was established at the University. By the end of the month, there were approximately 400 cadets on campus, and that number would swell to 727 by October. They were greeted by University President George P. Rea, who hoped that they would “have a full share in our college life and make their own valuable contribution to it.” Rea’s warm sentiments were counterbalanced by the unit’s commander, Col. Ernest C. Goding, who sternly reminded the young men: “Your main mission is to study and to study long and hard” and “[t]he standards of Drexel are very high. . . I urge you to exert your utmost energy so that you will get the most out of the course both for yourself and your government.”

Cadets had little time for socializing, but who could blame them for joining a co-ed in the tradition of rubbing the toes of “The Water Boy” statue for good luck?

All the cadets assigned to Drexel were in training programs for engineering. Under the ASTP, the engineering curriculum was broken into basic and advanced phases. The basic phase, meant to be equivalent to the first one and a half years of college, consisted of three 12-week terms of “general engineering” that were composed of classes in English, history, geography, geology, mathematics, physics, chemistry and engineering drawing. The advanced phase was intended to provide coursework normally found in the second half of the college sophomore year and develop the skills of the trainee to a point “commensurate with the Army’s needs.”

The necessity of covering such vast amounts of material in so little time meant that the daily routine for the cadets at Drexel was intense.

There was a grueling 59-hour weekly schedule made up of 24 hours of class and laboratory, 24 hours of study, six hours of physical education, and five hours of military training and drill.

James F. Sterner, a cadet from Wilmington who had completed his freshman year at the University of Delaware before joining the Army, called the program “100% business.”

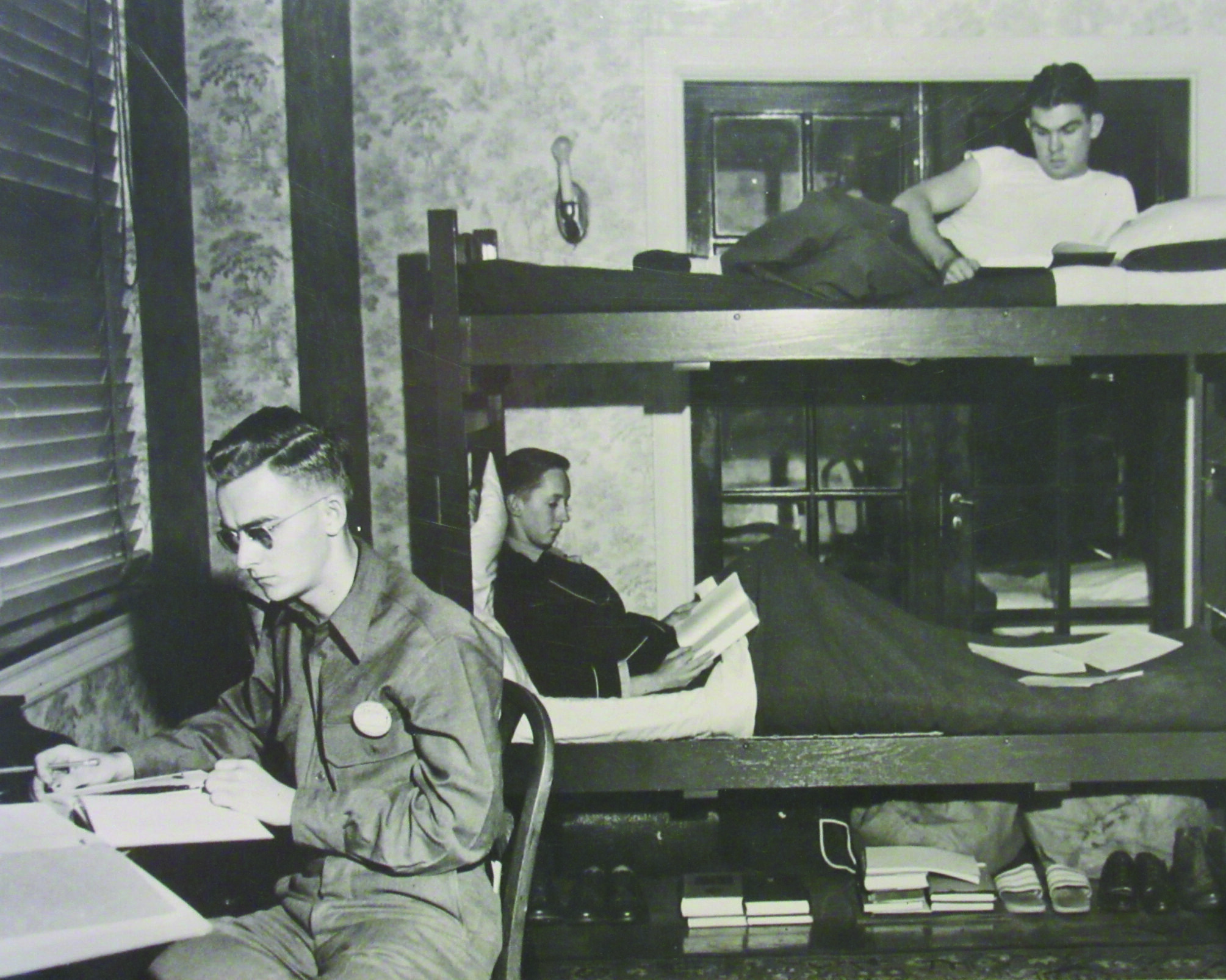

The cadets were billeted on the second and third floors of the Hotel Philadelphian at 39th and Chestnut streets (now the Chestnut Hall Apartments) and ate their meals in the hotel’s ballroom turned mess hall. York native Philip E. Rohrbach detailed the daily routine of the Drexel cadets:

We would get up at 0600 hours and go down for breakfast by 0630 hours. We would always be dressed in our Class A uniforms. At 0730 hours, we would form in a column of threes outside the hotel and march down Chestnut Street to Drexel. It made no difference what the weather was like, we would march down to the school in the morning for 0800 hour classes. At 1130 hours, we would march back for lunch at 1200 hours and march back to school for 1330 hours class. At 1630 hours we would march back to the hotel for dinner at 1730 hours. After dinner, we would hit the books until whatever time we finished our homework assignments.

Each weeknight, there were strictly enforced study hours from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m., and bed check was 11 p.m.

Given the hectic pace of study, it is hardly surprising that many cadets struggled to keep up. Only weeks after Drexel welcomed its first cadets to campus, dozens had flunked out of the program. Cadets voiced their frustration in The Triangle, criticizing the ASTP program and the seemingly unattainable standards that Drexel appeared to be setting. One cadet joked, “When someone invents a machine in which you put a man, with a year and a half of high school math, in a chair, turn on a switch, and bring forth a young Einstein, then, and only then, will Drexel be able to uphold the standards it has set.”

A cartoon from the Aug. 27, 1943 issue of The Triangle pokes fun at the overscheduled cadets.

The Drexel cadets may have had a point. Army programs at other schools, and in other subjects, were not as rigorous. Alexander Hadden, an ASTP cadet studying French at the University of Illinois, described his program as a joke, with rampant cheating that contributed to an atmosphere “so ridiculous that almost no one took it seriously.”

If the Drexel cadets expected sympathy, they certainly did not receive it from other Drexel engineering students. An anonymous student responded to the cadets’ gripes in The Triangle by reminding them of Drexel’s reputation, and pointing out that it was common for all engineering students to struggle:

Drexel’s standards are high! This is an engineering school, not a “country club.” …At Drexel an average of one-third of the original entering class of engineers graduates… We who have studied to pass in the face of these high standards, who have in many cases worked hard to pay for what you get for free, who pride ourselves that someday we will be graduates of a school producing good engineers, don’t want the standards lowered…Drexel has an obligation to its thousands of graduates — past, present and future — to maintain its standards and reputation.

While there were efforts to meld the ASTP cadets with the student body by hosting dances and concerts, wartime issues of The Triangle abound with examples of sparring between the civilian students and the ASTP-ers. But the simple fact was that the cadets had very little time to socialize, and the brutal cadence of the program led to more and more of them flunking out.

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

As 1944 began, persistent rumors circulated about the future of the ASTP program. With U.S. forces committed to battlefronts all over the globe, the withholding of intelligent and fit soldiers on college campuses became even less tenable.

The cadets themselves were keenly aware of how little they appeared to be contributing to the war. Cadets joked that ASTP stood for “All Safe ’Til Peace” and the unofficial “ASTP Anthem” included the following stanzas:

Take down your service flag Mother,

Your son’s in the ASTP

He won’t get hurt by a slide rule

So gold star never need be.

We’re just Joe College in khaki

More Boy Scouts than soldiers are we

So take down your service flag Mother,

Your son’s in the ASTP.

Even the daily march to campus could be a reminder of how war seemed to be passing the cadets by. Cadet James Nichols recalled they were sometimes heckled as they marched down Chestnut Street with “My son is in the South Pacific. How come you get to live in a hotel and go [to] school?” or “My boy was shot in Africa. He’s in the hospital. Why aren’t you fighting?”

Drexel ASTP cadets studying in their room at the Hotel Philadelphian, where all the cadets lived and ate their meals in the ballroom.

American units fighting in Italy were suffering tremendous casualties, the invasion of France was looming, and even though Congress had approved the drafting of fathers, the Army was still short some 200,000 men. Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall wrote to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson on Feb. 10, 1944, laying out in stark terms the challenge and its potential remedy:

I am aware of your strong feeling regarding the [ASTP]. However, I wish you to know that in my opinion we are no longer justified in holding 140,000 men in this training when it represents the only source from which we can obtain the required personnel, especially with a certain degree or intelligence and training, except by disbanding already organized combat units. . . our need for these basically trained men is immediate and imperative. [emphasis original]

Stimson had no choice but to drastically reduce the ASTP or risk seriously inhibiting the Army’s ability to effectively fight the war. On Feb. 18, 1944, just seven months after the first cadets arrived at Drexel, the Army announced that the ASTP would be reduced from 145,000 to only 35,000 men.

“The dear days at college are over”

Even before the reduction of the ASTP was announced, there were attempts to assuage the concerns of the cadets. An article in the Army’s Infantry Journal reminded them, “You can be certain that you would never have been picked out of several million men and sent to school for the better part of a year, unless there was a coming need of trained and educated men of your caliber” and that at the end of their training “every soldier in the ASTP will be ready for greater war responsibilities.”

Indeed, some ASTP-ers considered themselves a “substantial cut above the average G.I.” However, they would soon learn those “greater war responsibilities” would require neither their above-average intelligence nor specialized training.

Part of the cadet’s exercise regime at Drexel was a mile-long obstacle course that included a 60-foot stretch across telegraph poles.

The announcement that the ASTP would be shut down at Drexel was met with mixed emotions. In the preceding months, Philip Rohrbach had watched as half of his class washed out and he believed, “I would have flunked out at the end of term, if it had lasted.” Cadet Allan Howerton didn’t like it at all: “That we were full of resentment was an understatement. We were mad as hell and powerless to do anything about it.”

The consensus expressed by some in The Triangle was that the ASTP-ers had gotten a “raw deal.” Former cadet Pfc. George Hart put the feelings of many to verse:

Say good-bye to the slide rules and textbooks,

Say good-bye to the co-eds and class.

And take one last spree

As you finish term III,

For you’re going right out on your — ear!

It will make little difference to study,

You’re just like the rest of the dupes,

For win, lose or draw,

You’ll be eating it raw,

And you’re heading right back for the troops!

The dear days at college are over,

The profs and the T-squares are gone,

So cry in your beers,

You poor engineers,

You’ll be digging a ditch from here on!

“You’re here for the duration. . .”

The Drexel cadets left Philadelphia on March 29, 1944, and began a 60-hour train ride South. On April 1, 1944, the train pulled into Camp Claiborne, and was welcomed by a military band. The jovial gesture fell flat with the former ASTP-ers. One cadet quipped, “Better if they played a funeral march, as far as I’m concerned.”

James Sterner was optimistic, at first. Camp Claiborne was an engineer training center and he thought the Drexel cadets would be transferred to engineering units. When an officer announced, “‘You are now members of the 84th Infantry Division,’ we couldn’t believe it. We were the bottom of the food chain.” Sterner turned to his Drexel buddy Donald Stauffer and said, “Surely, the Army is playing an April Fool’s joke on us.” Most of the 396 cadets were assigned to infantry regiments; very few were assigned to more prestigious and safer duties in its supporting units.

Louis E. Keefer, a former ASTP-er turned infantryman whose book “Scholars in Foxholes” is the definitive history of the program, summarized the fate of the cadets. “The bottom line was that the program had been curtailed so abruptly that classification specialists had little opportunity to match trainee records against receiving unit vacancies to determine logical assignments,” Keefer wrote. “[E]very smart trainee knew the Army was treating him as just another warm body.”

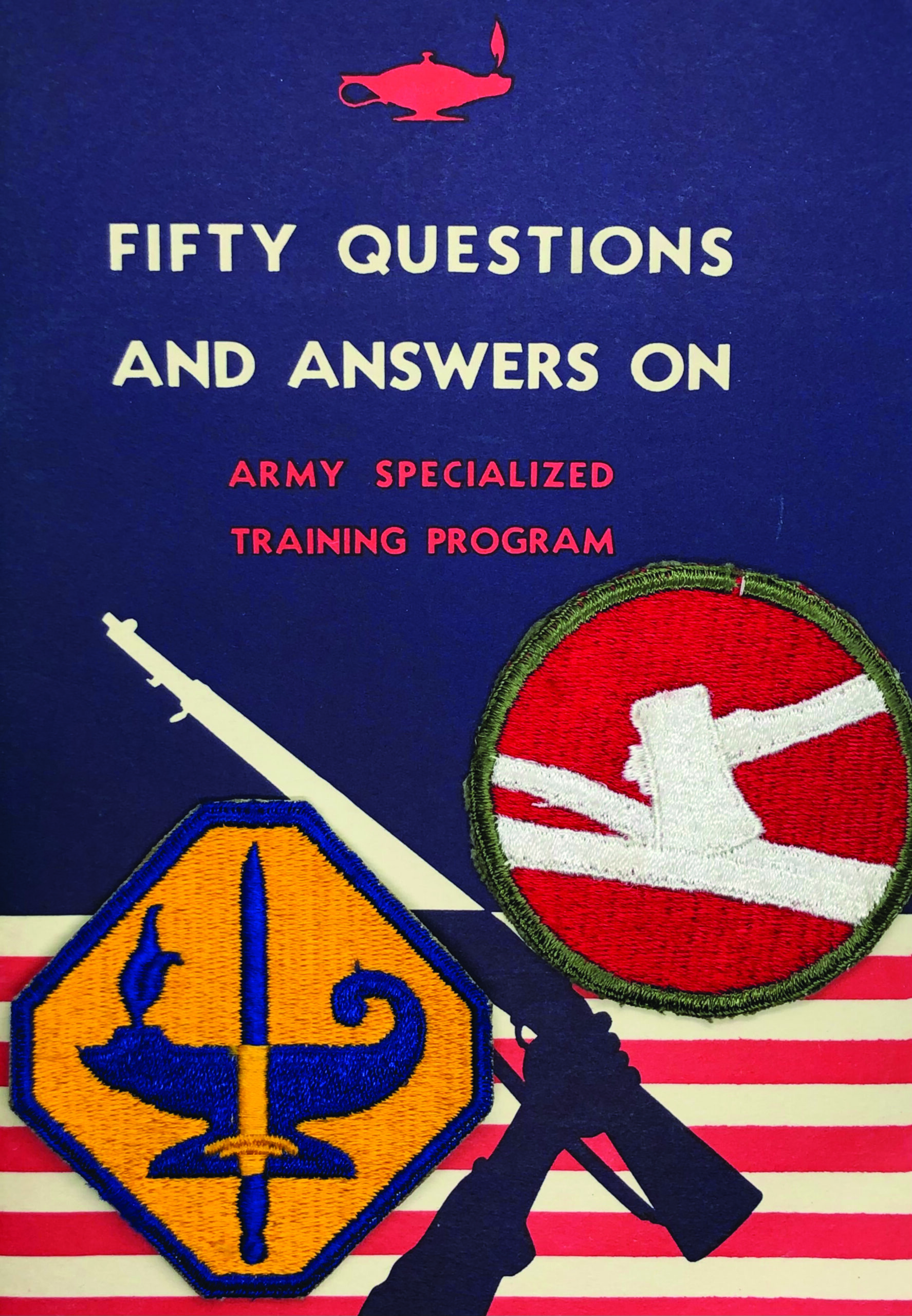

The insignia of the ASTP (left) is the lamp of knowledge superimposed with a sword. Cadets sometimes referred to it as “the pisspot and reamer” and “the lamp of flaming ignorance.” At right is the insignia of the 84th Infantry Division, the “Railsplitters,” where many Drexel cadets were eventually assigned, to their dismay.

Serving as a rifleman in an American infantry division was exceptionally dangerous, recounts John Ellis, author of the history “The Sharp End: The Fighting Man in World War II.” They more than any other group assumed the greatest responsibility for confronting the enemy, and riflemen suffered the greatest number of casualties, despite being a proportionally small part of the Army.

Cadet Howerton viewed his new circumstance with dismay:

Meek-faced young men gazed across the chow table into the sunburned faces of men hardened by months of tough training in the sand hills of Texas and the scruffy woods of Central Louisiana. Most of them felt green, out of place at first, believing themselves misfits. Barracks and pup tents were a great contrast to hotels or college dormitories. M-1 rifles were heavy compared to slide rules, and 25-mile marches were not like strolls around the campus with a pretty co-ed.

The anger felt by the former ASTP-ers was likely matched by the resentment of the sometimes older, and usually less-educated, soldiers in the units they joined. The sergeants and corporals delighted in assigning the “wise-ass college boys” to menial duties. The welcome Howerton and his Drexel comrades received from the first sergeant of his new company was likely typical and in Howerton’s words, “summarized our condition succinctly:”

‘Men…you may have noticed that the ASTP boys we’ve been hearing about have come. They’re the new guys you see here. The ones who look like they haven’t seen the sun this year… You ASTP boys will have five weeks of special training. No books. You’ll learn to crawl in the mud under f—in’ bullets, scale goddamn walls, and kill f—in’ Germans and J–s… Them [sic] that don’t get a round up their h’ass during training will be assigned to K Company. You’re here for the duration…’

The infusion of the ASTP-ers had the immediate effect of not only bringing the troops up to numerical strength, but also increasing their overall combat effectiveness. In some units, ex-ASTP-ers held impromptu classes in “readin’, writin’ and ’rithmatic” for their less literate comrades.

Through the accelerated training program and sheer necessity, the friction between the “whiz kids” and the “old men” was overcome. Now a full-fledged infantryman, Howerton reflected as the 84th Infantry Division prepared to ship to Europe in September 1944:

It had not been a happy time and was as close to hell as most of us had ever been. Yet amid all the grousing and the frustrations, large and small, a transformation had occurred. We had come to Claiborne as students. We were leaving as soldiers. . . although we were loath to admit it, our forced merger with the old guys had made us better men.

“You college guys piss and bleed just like everybody else…”

As confident as the Drexel cadets may have been after their crash course in infantry tactics, no amount of training or intellectual acquity could guarantee their safety or survival. Howerton’s platoon sergeant warned him before the 84th Infantry Division left Camp Claiborne: “You college guys piss and bleed just like everybody else, don’t forget it.”

The 84th Division suffered heavy casualties when it entered combat on the German frontier near Geilenkirchen in late November 1944. Among the first killed and wounded were former Drexel cadets. Pfc. Charles Randall Jr. of Waterloo, Iowa, who had joined the division from Drexel, was killed within days of arriving on the front — just three days after his 20th birthday. Around the same time, another Drexel cadet, Pfc. Class Philip Rohrbach, was wounded in the head by a German grenade and taken prisoner. When he was released after five months of captivity, he weighed just 99 pounds.

As the 84th Division fought across Europe, the Drexel ASTP-ers demonstrated that they could be excellent combat soldiers. Harold L. Howdieshell, a Drexel ASTP alum, was awarded the Bronze Star medal for capturing 17 Germans in February 1945 and earned an officer’s commission. On March 1, 1945, Lt. Howdieshell’s company was pinned down as it attacked enemy positions near Berg, Germany. In front of the rest of his unit, Howdieshell spotted a German machine gun, and after pushing two of his men to safety, began throwing grenades at the enemy. While preparing to throw his fifth grenade, Howdieshell was shot and killed instantly.

Although there are no statistics on the overall performance of former ASTP cadets in combat, Howerton, himself having earned a promotion to sergeant, reviewed his own company’s records after the war. He found that compared to the soldiers they joined at Camp Claiborne, fewer of the ASTP men were killed, they were less likely to have been evacuated for minor medical ailments and they were better disciplined. There is additional evidence that the former ASTP cadets made excellent soldiers in their new units, recounted in Peter Mansoor’s “The GI Offensive in Europe: The Triumph of the American Infantry Division 1941–1945.” For example, the 102nd Infantry Division received approximately 2,700 ASTP cadets, and almost 100 of them earned officer commissions due to their exemplary performance in battle.

A lasting record

From a military perspective, the ASTP was no success. It deprived the Army of valuable manpower at a time when it desperately needed to maintain its fighting units, and it then unceremoniously dumped tens of thousands of its brightest soldiers into some of the most dangerous duties.

However, a lasting legacy of the ASTP survives outside the battlefield. The ASTP is credited with some post-war changes to college education; namely, a general speeding up of course instruction, a greater emphasis on technological and mechanical training and the “all conversational” technique of teaching foreign languages. Many former ASTP-ers returned to college after the war and used the G.I. Bill to fund their education. James Sterner believed that the ASTP had made him a much better student and credited his time at Drexel as the reason he was able to gain admission to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute after the war.

For historians of World War II, perhaps the greatest benefit has been the number of memoirs written by former ASTP-ers. Veterans of the program like the Drexel cadets chronicled here appear to have written proportionally more than maybe any other demographically identifiable group, and thanks to their erudition and observations, historians have a wealth of personal perspectives of frontline combat in the final year of World War II.