Photos by Alex Boerner

Hollis Chatelain, BS ’80

Hollis Chatelain dreamt she was in a room the size of a football field. At the other end was a boy, bright orange and gazing directly at her, beckoning her to approach. As she drew closer, she could see images of children floating over his face. Some were laughing and going to school, some were already working. One was a child soldier, another a girl forced into prostitution.

“He was asking me to pay attention, to listen to the stories of our children,” she says, “because they were in peril and people weren’t realizing it.”

Applying colorful dyes to fabric is a distinctive element of Chatelain’s quilt design process.

Chatelain is an artist whose ideas come to her in dreams that recur if she ignores them. She’s been having nearly monochromatic dreams for more than 20 years, most of them about social and environmental issues, which she turns into art quilts that are technically and emotionally intense.

She knew she had to give the boy she dreamt of a voice, so she spread an expanse of white cotton broadcloth bigger than a king-size sheet across a worktable in her sunny North Carolina studio and began painting. Chatelain uses dye the thickness of maple syrup. It soaks in and becomes part of the fibers, unlike paint, which is easier to use but just lays on the surface. First, she painted the boy’s eyes, intensely gazing directly at the viewer, just as she had seen them in her dream. She added waves of orange, then used soft, waxy Prismacolor pencils to sketch the outlines of not just the boy’s face but also the ghostly other faces that represented those imperiled children from all over the world.

Chatelain had taught herself to draw faces while in Africa, where she served in the Peace Corps for two years after she graduated from Drexel with a degree in design in 1980. There she met her husband, Reynald, a volunteer from Switzerland who in his time on the continent had created a library, a garden cooperative, an artisan’s center and a model farm. It was love at first sight. They married in a traditional village ceremony, the wedding party dressed in colorful Kente and Adire cloths, strands of traditional beads around the women’s necks. She gave birth to their first child in Togo, delivered under kerosene lamplight by Togolese midwives in a bush hospital.

When her Peace Corps stint was up, they moved to the Philadelphia suburbs, and then to Switzerland. There are few opportunities to volunteer in Africa from the United States unless you’re sponsored by a missionary group or USAID. There would be more prospects, coming from Switzerland. At first — now with two children — they planned to stay in Reynald’s home country, but then they saw an ad for volunteers in Burkina Faso.

“We just looked at each other and knew that we were going to go,” she says.

They stayed for five years, Chatelain working with solar cookers but also teaching herself and others to draw. They moved to Mali, then Benin, for a total of 12 years in Africa. They adopted a child from an orphanage and eventually returned to the States so their children could become acclimated to American culture before college. Chatelain began painting the people she missed the most, and Reynald traded in his career leading humanitarian organizations to raise the kids and manage the business side of Chatelain’s work.

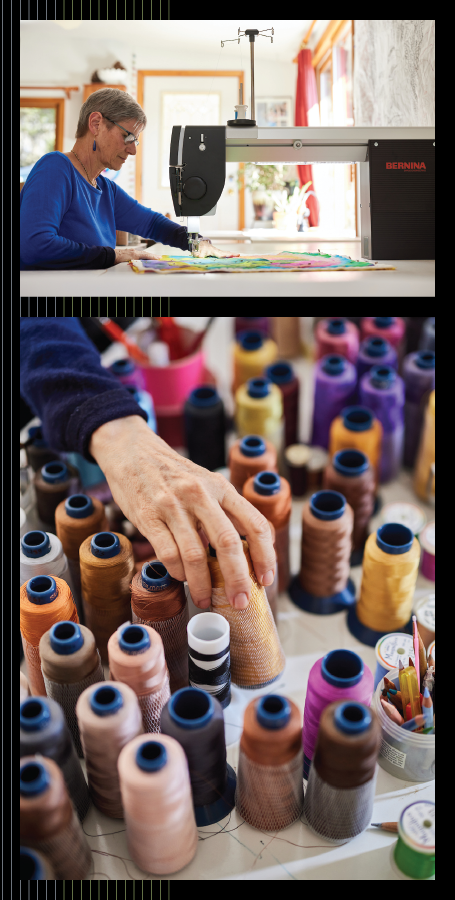

Painting is just one step in Chatelain’s process. Using a 1994 Bernina sewing machine, she adds anywhere from 18,000 to 25,000 yards of thread, crafting the planes of a face, the shape of a body.

“Quilting is like anatomy 101,” she says. “You’re in essence creating the structure through the contours of the different parts of the body.”

Chatelain studied the human form in life drawing classes at Drexel, and also pored over anatomy books to deeply understand the bones and muscles, the sense of movement. She free-hands the quilting in one-eighth-inch stitches, changing her sewing machine’s thread about 200 times a day.

Chatelain fits into a rich historical tradition of quiltmakers plying their craft in the service of human rights and social causes. One dream came to her in a hot pink. It depicted one of her daughters, who has no children, standing in a field, a baby on her hip, staring directly at the viewer. The background sky was covered with quotes about women. Chatelain painted it in 2015 and began quilting, stitching in 400 quotes in her own handwriting. The work began to feel technical, though, so she set it aside and — with encouragement from students she teaches — created a coloring book instead, introducing children to the joyous lives of people in Africa. When she returned to the quilt in 2018 she knew why it was hot pink: Women in pussy hats had just marched on Washington.

“Equality” is the result of a series of dreams in which Chatelain pictured her daughter and her granddaughter surrounded by crows and hundreds of quotes about the power of women.

That quilt and two others were hung this spring in an 18-quilt display in the Clinton Presidential Library, a show that was supposed to coincide with the 100-year anniversary of women earning the right to vote, but COVID delayed it. One of her entries depicts two African American women wearing bright white “I Voted” stickers, to highlight that many of them did not get the right to vote until passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965.

Traditionally, sewing machines have teeth called feed dogs beneath the foot, pushing the fabric ever forward. Then manufacturers responded to quilters’ requests to make it possible to lower the feed dogs, freeing the artist to move the fabric as she chooses. Quilting, in all of its forms, is a $4.2 billion market in the United States, according to the Craft Industry Alliance trade association. About 20 percent of that comes from art quilters.

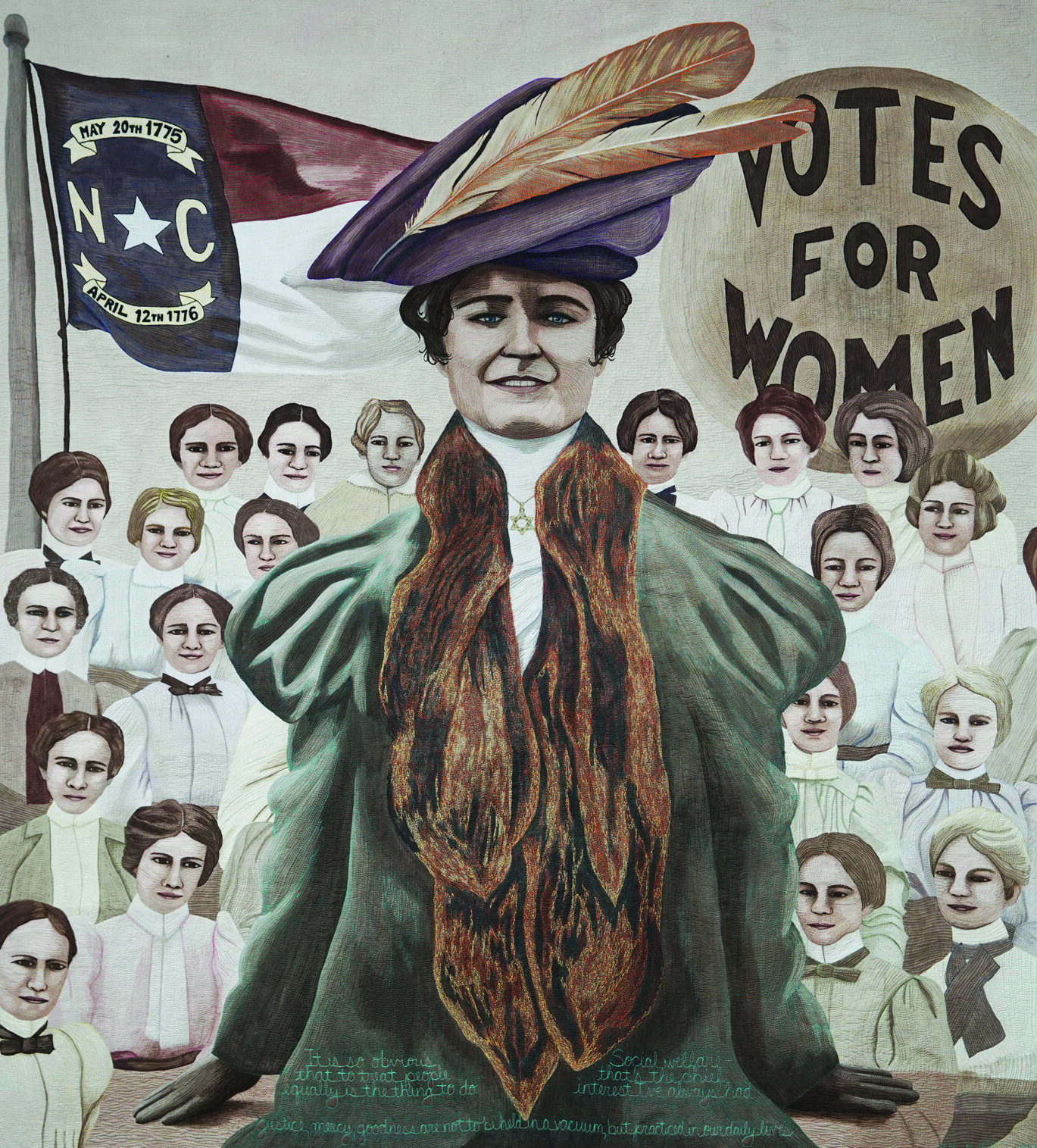

This quilt was displayed in the Clinton Presidential Library this year in honor of the 100th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote.

Chatelain’s work has been shown around the world. In 2020, 25 of her pieces served as backdrops for a forum on diversity and inclusion at the Washington, D.C., offices of consulting firm Booz Allen. It was a dream 15 years in the making.

“I want my work to speak to people, to bring awareness to subjects, to move people, to emotionally affect people, to make them think about these issues,” she says. “That’s one of the reasons I work as large as I do, because it’s harder to walk away from a really large piece.”

Her piece, “Exodus,” dreamed all in white, depicts a woman grieving. Behind her is a line of refugees trudging out of the picture. On the right is a village, fading away. It is about the Darfur War, dreamt during the height of the genocide.

“The people who left Darfur weren’t poor,” she says. “They left because they were being attacked. So they weren’t in rags. They actually had beautiful clothing, beautiful scarves, and I wanted to somehow portray that, but it was all faded.”

In museums, people stand in front of “Exodus” and weep.

The line of refugees depicted by Chatelain in “Exodus” came to her in a dream during the Darfur War.

Another of Chatelain’s works is of Archbishop Tutu, his purple gown so richly quilted that the fabric appears to drape and flow. Drawn toward him “as if he were the pied piper” are children, their faces eager. In Chatelain’s dream, he was standing in a field, representing hope, tolerance and love. She didn’t feel she could quilt it without communicating with the archbishop, though, so that she could get it right. She was teaching a quilting workshop in 2005 when a woman invited her to teach somewhere else. “Archbishop Tutu will be there,” the woman said. So they met. He looked through her portfolio, running his fingers over the faces, then gave her his blessing to do the piece. The children come from countries around the world. She researched what they would be wearing, how they would style their hair. When it was done, she sent it to Michigan State University, where Tutu was slated to speak. Afterwards, he sent her an email.

“We were photographed in front of your lovely work. You got my nose right. Thanx for that. Luv & Blessings, Arch.” The quilt won 2007 Best of Show at the International Quilt Festival in Houston, the largest annual quilt show in the world, with more than 60,000 attendees and a top prize of $10,000.

“He’s larger than life size, so it’s a really big quilt,” she says. “During the show people were just sitting in front of it, cross-legged, staring at it for hours.”

Chatelain’s portrait of suffragist Gertrude Weil is one of many quilts held in public and private collections around the world. This one belongs in a public building in Chatelain’s hometown.

Chatelain’s textile portrait of suffragist Gertrude Weil will soon hang in one of the public buildings of Weil’s hometown, Goldsboro, North Carolina. Others are in the permanent collections of the owners of The Discovery Channel; The American Embassy in Mali; the Durham Public Library in North Carolina; and the National Quilt Museum in Paducah, Kentucky. They’re in private collections around the world.

“Hollis’ quilts come alive when you look at them,” says Deb Geyer, executive director of the Marion, Indiana-based Quilters Hall of Fame, which last year held a 30-year retrospective of Chatelain’s work. “She sees something in the person and then expresses it through her art.”

Chatelain believes work like hers can change minds.

“Art can make people think, and taking time to look at it can make a big difference in the world,” she says. “Activist art or political art doesn’t have to be shocking. Sometimes a whisper can be more powerful than a scream, and that’s what I want my art to do, to pull people in.

“You see it from the distance, and it is pretty graphic,” she says. “But then, if you’re willing to approach, there’s the gift of the stitching. And that tells another story.”