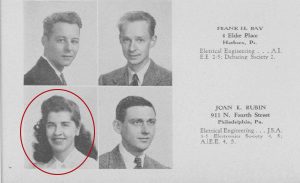

The decision to enroll as one of the first female engineering students at the Drexel Institute of Technology was very easy for Joan Rubin (BS ’47): Drexel had women’s restrooms.

It seems like a silly requirement, but the lack of a woman’s restroom was the exact reason one University of Pennsylvania dean had denied Rubin’s request to transfer into the engineering program as a Penn freshman.

“I was only 16. I was too naïve to say, ‘Well, what does your secretary do?’” she says, remembering the perfect comeback to an argument from over seven decades ago.

Her actual response was even better: she enrolled in Drexel’s then School of Engineering and graduated in the institute’s first class of women engineers. The first female electrical engineering graduate, Rubin walked at the 1947 fall commencement ceremony alongside Alice Forbes (BS ’47), the first female chemical engineering graduate.

Drexel’s historic moment occurred during an important time for women in engineering. Two years earlier, women made up half a percent of the country’s graduating engineering class. Now, 70 years later, the number is 20 percent both nationally and on campus — and, hopefully, it will continue to grow.

Since the beginning, women engineers at Drexel have helped mold the institution into the forward-thinking university it is today. But their influence and reach goes far beyond campus, or even Philadelphia. Some of them created or joined a student organization that jump-started the Society of Women Engineers (SWE), a nonprofit professional organization that currently has about 30,000 members and chapters on 300 college campuses.

Penn, it should be noted, didn’t admit a woman into an undergraduate engineering degree-granting program until 1958 — 16 years after Rubin first applied and after Drexel had already graduated 24 female engineers.

“I guess they finally got a women’s restroom,” Rubin says.

The First Dragons of Their Kind

It was a long time coming, considering women first joined the American engineering field in the late 19th century. By the time the 19th Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote was ratified in 1920, women had earned all levels of degrees in a variety of engineering fields, though they were a select few. Opportunities for female engineers became more pronounced after the draft for World War II, though employers and the general public still doubted their abilities and suitability to the engineering field.

During that time, Drexel, already well-known as a technical institute, enrolled its first class of women, 17 students, in 1943. There were still challenges on campus, of course.

For all of the hullaballoo that women’s restrooms had caused for Rubin at Penn, she and her peers didn’t have any restrooms near the engineering classrooms in Curtis Hall. They did, however, have access to a men’s locker room in the Main Building: It was the only entrance to Drexel’s machine shop.

“We would sing ‘She’ll Be Coming ’Round the Mountain’ to announce that we were going through the locker room. There was no other way you could get to the machine shop, and you just had to work around it,” says Alma Forman, PE (BS ’49), Drexel’s first female civil engineering graduate.

Another thing to work around? For some women, it was the male professors, who created more problems than the male students. One of Forman’s professors told her she was the biggest mistake in the class (though she did pass his course). Rubin’s calculus professor told the class they didn’t have to worry about her being at school to catch a man since she was already married.

“And that was nothing. That was to be expected,” Rubin remembers.

Not only was prejudice to be expected, but it was expected to be dealt with individually. Though they were easy to single out, Drexel’s women engineers didn’t know one another because they didn’t take the same classes.

And some didn’t stick around long: of the four women who started as female chemical engineering majors alongside Forbes, she was the only one left at the end of her freshman year, and every year until graduation.

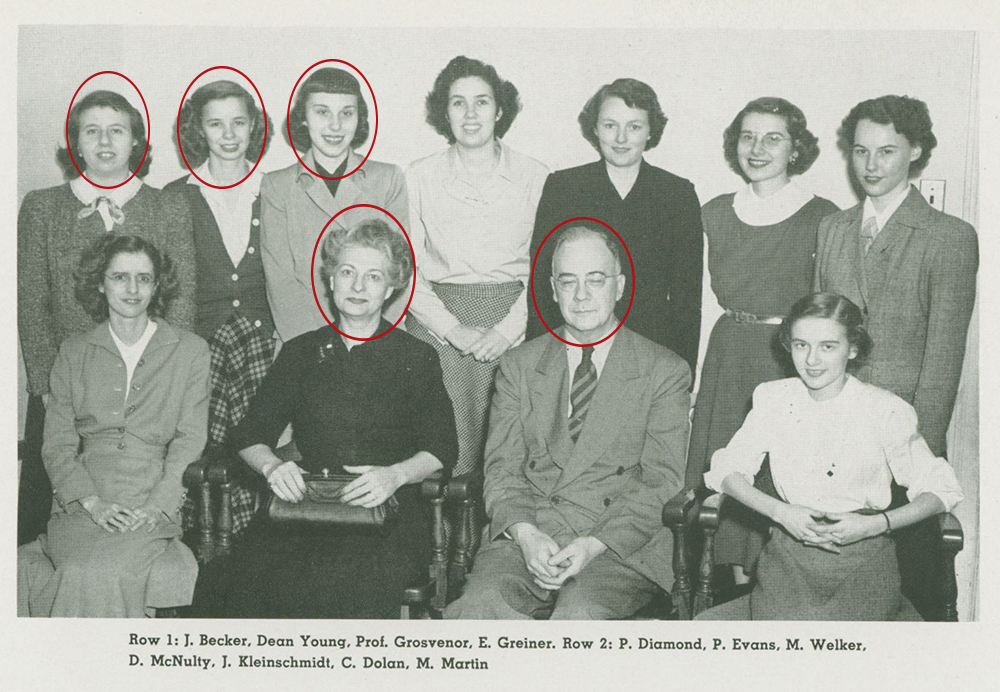

In an effort to bring the women engineers closer, Dean of Women Dorothy Young hosted a tea party in 1945 to introduce the students to each other. It was so successful that the women started eating lunch together every day to discuss their similar experiences.

By the following fall, about 20 women had formalized their lunchtime support group as an academic and social club called the Society of Women Engineers. The first year’s program consisted of technical speakers, social events and dinners for graduating seniors like Forbes, who is thought to have been the club’s first president.

As the club grew and gained recognition at Drexel, so did the number of women engineers on other college campuses, especially on the East Coast. But they were just as isolated and independent as the Drexel students had been. Some spark, some catalyst, was needed to bring them together — but what?

‘The Nucleus From Which Grew the National Society of Women Engineers’

As it turns out, the idea of a greater “Society of Women Engineers” came from a freshman English term paper, which was written by Drexel mechanical engineering student Phyllis Diamond Rose (BS ’53) in the summer of 1948, remembers Forman.

“She decided to write about women in engineering and when she brought this up, we started thinking about what other colleges had women engineers,” says Forman.

Rose passed her class — and sparked a national movement.

In the spring, the Drexel students sent questionnaires to major engineering colleges asking if those institutions accepted women in engineering courses, if they had an organization similar to the society at Drexel and what those students did after graduation. The answers revealed that although some of the colleges did accept women, they weren’t organized in any groups and they either hadn’t graduated yet or revealed what kind of jobs they might be holding.

It was up to the Drexel women to unify their colleagues, and they succeeded beyond their wildest expectations.

The group, chaired by Forman, held a regional conference for women engineers in April 1949 that was attended by 83 engineering students from 19 colleges. Held at the Sarah Van Rensselaer Dormitory (which was then women-only), the event was completely financed by Drexel, thanks to Forman’s collaboration with Drexel President James Creese and School of Engineering Dean Robert Disque, who spoke at the event.

That regional conference is not considered the founding meeting of present-day SWE, since it only involved students and did not create a formal governing body. Still, the meeting introduced the colleges and students who officially started the national SWE at its first national convention the following year. In fact, several of the “first ladies,” or founding and charter members, were Drexel students, including Forman, Rose, Phyllis “Sandy” Evans Miller (BS ’50), Eleanor Gabriel (BS ’51) and Doris McNulty, PE (BS ’58).

As A.W. Grosvenor, an assistant professor in the Mechanical Engineering Department and the Drexel group’s faculty advisor, would later say: “The initial members of the Drexel group, the nucleus from which grew the National Society of Women Engineers, were enthusiastic and hard working. They were determined to prove themselves in a profession dominated by men.”

After the Boom

Drexel’s first women engineers not only proved themselves in a profession dominated by men, but also ensured there would be space for other women. Several students, including Forman and McNulty, even obtained their professional engineering licenses at a time when not many engineers, male or female, had them.

Rubin and Forbes’ legacies as Drexel’s first women engineers remain an important part of the College of Engineering, which in 2014 celebrated 100 years since conferring its first degree. Rubin worked at Bell Laboratories and RCA before teaching math at a high school and working with her engineering husband. Forbes worked as a chemist in the Franklin Institute’s rubber lab before raising 10 kids; she passed away in 2013.

After paving the way for future women engineers, Drexel’s first class of SWE members continued to work with those who followed in their footsteps. Forman, Miller and McNulty all remained involved with SWE through various leadership roles, with Miller starting a SWE section in Pittsburgh and Forman at Temple University. After working in the industry, Forman later became a professor of mechanical engineering and later the director of computer services for Temple’s School of Engineering and Architecture.

Though Miller passed away in 1982, the “first ladies” continued to occasionally meet, even after McNulty died in 2009. The bond that birthed the Drexel and national SWE groups holds up even 70 years later.

“The Society of Women Engineers is a great developing tool for women,” Forman says. “It develops leadership. It’s great for networking. You find support in unusual ways. And that’s why it was formed in the first place: as a support group.”

Generations of these support groups have passed through college campuses across the country, but it’s a special tradition at Drexel, which has historically graduated large numbers of women engineers.

Today’s SWE Drexel chapter holds 134 registered SWE members, including 20 officers. Much like the national organization, the Drexel chapter holds workshops, guest speakers, community outreach events and other opportunities to help women engineers grow academically, professionally and socially.

“While Drexel is where I learned to be an engineer, Drexel SWE is where I found my passion for being one,” says Meaghan Paulosky (BS ’15), the group’s recent former president. “I’ve learned so many lessons that will carry me throughout my engineering career and eventually bring me back to Drexel SWE to share with the next generation of students.”

As a member of the first generation, Forman reflected on what SWE accomplished when speaking at the Philadelphia SWE conference held on campus this past winter.

“It’s kind of awesome looking back at this group that is now so large. It gives you a feeling of growth and satisfaction that there was a need, especially when there’s still a need today,” she says.