In May, two of Philadelphia’s institutional giants made a big splash in the history books.

The Academy of Natural Sciences, the nation’s oldest natural sciences research institute and museum, sought a science-based university partner to help it reach its full potential. After considering all the possibilities, the Academy’s top choice was clear: Drexel. Negotiations began, papers were signed, and late this spring, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University became a reality.

The new affiliation will enable Drexel to take a national leadership role in environmental science and environmental policy—two of the Academy’s specialties—and help the University develop new programs and courses in fields ranging from geology to environmental policy, as well as new departments, centers and institutes.

For the Academy, the partnership provides crucial new resources for its scientists and museum—everything from teaching opportunities to tapping into Drexel’s technology and media arts programs for exhibits—and puts the institution in a better position to take advantage of its unique strengths.

In other words, the partnership appears to be a win-win—something that figures to benefit both the Academy and Drexel for decades to come. But what exactly is the Academy? And why did Drexel jump at the chance to forge this historic partnership?

Founded in 1812, the Academy is a public museum and (more importantly, from Drexel’s point of view) an active research institution. Its collection of 17 million biological specimens offers a remarkably detailed catalog of the diversity of life on earth, from two-week-old plant specimens to 300-million-year-old fossils. In the field and in the laboratory, Academy scientists are busy naming new species, publishing scientific papers and recording environmental change.

In August, we pulled five Academy staff from their intensive, research-filled schedules to ask them about what they do—and why that work matters. What we present here, then, is an eclectic bunch of scientists and collections managers—the bird guy, the shell guy, the bone guy, the wetlands ecologist and the archivist—that offers a small but revealing window into the incredible world of Drexel’s newest partner.

Tracy Quirk, Assistant Scientist, Patrick Center for Environmental Research

You could say that Tracy Quirk’s “office” is a hostile work environment.

As assistant scientist at the Academy’s Patrick Center for Environmental Research, Quirk spends most days of the week aboard a boat, cutting through the marshlands of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, measuring how the wetlands of the Mid-Atlantic are changing. In sweltering heat and soupy humidity, she trudges through knee-deep mud while fighting off hungry mosquitos, occasionally stopping to take cover while a lightning storm passes by.

Despite the harsh conditions, there is no place else she’d rather be.

Quirk came to the Academy in 2010 as the Ruth Patrick Postdoctoral Scientist, a position named for the pioneering ecologist who founded the environmental science branch of the Academy in the 1940s. The Academy didn’t have a wetlands ecologist at the time, so Quirk filled a niche in the environmental science staff. Two to three days out of the week, Quirk climbs into full-body waders and spends the day in a boat monitoring the wetlands around Delaware Bay and Barnegat Bay. It’s a treat for her, she says, to experience the outdoors in this way, especially since she grew up in the “concrete jungle” of New York City. In the field, she measures the accretion of the coastal sediment to see if it’s growing or sinking relative to sea level. She also tests for water and soil quality and she records and analyzes all of this data for eventual publication.

Sharing her findings through publication is quite possibly the most important part of her job; it educates the scientific community and the public at large on the changes in these fragile ecosystems. The health of local wetlands affects everyone, she says. “Wetlands are a critical habitat for fish, crabs, shrimp—anyone who likes to eat these things should care about the existence and health of wetlands,” she says.

The health of wetlands is a major worry today, with coastal populations growing and sea level rise a seemingly imminent threat. “Wetlands,” she says, “can be an indicator of what’s to come.”

Even still, Quirk says, there are a lot of “unknowns” when it comes to these wetlands. She considers it her duty to help change that.

When scientists were conducting research into the impact of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, they looked to the Academy’s collection of oyster shells.

Paul Callomon, Collection Manager, Malacology

An apparent, almost paternal pride comes over Paul Callomon when he talks about the malacology collection at the Academy.

He’ll tell you it’s one of the most historically rich collections in the country—and the third largest in the world. He’ll tell you it includes materials that can’t be found anywhere else. He’ll also tell you that it is among the six collections on Earth that must be seen by the folks in his line of work.

As collection manager of the Academy’s malacology holdings, Callomon is guardian of more than 10 million specimens dating back to the 1830s. He is responsible for the care and organization of the materials and for opening the collection to both the public and to researchers, who use the specimens to study everything from taxonomy to DNA to environmental change.

When scientists from the California Academy of Sciences were conducting research into the impact of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, they looked to the Academy’s collection of oyster shells from that region, which hold a record of pollution in the Gulf and can be used to show how the oil works its way through the food chain. No other natural history collection matched the depth and breadth of the Academy’s in meeting the scientists’ needs.

In addition to managing the materials the Academy already has, Callomon strategizes with the department’s curator to expand the collection. “We aim in the long term for the collection to grow, so it remains one of the world’s essential collections,” he says. Over the past 200 years, it has grown significantly, in large part because of the Academy’s field work. And besides, “we’re a museum,” Callomon says, “we don’t throw anything away.”

“A collection is like your permanent child,” he adds. “How it grows is up to you.”

The growth shows no signs of slowing, either, as scientists are discovering new species at the same rate now as they were in the 1850s. He and his colleagues manage to keep up, and are currently updating their database with an electronic inventory of the entire collection. There are roughly six million specimens down, four million to go.

Nate Rice, Collection Manager, Ornithology

Every Wednesday, Nate Rice guts bird specimens.

The birds are dead—they’ve either been collected specifically for study or fell victim to “window kill,” a fate often met by migrating birds in a world of skyscrapers. At a workstation in public view, Rice cuts open the birds and removes the soft tissue inside, including the eyeballs and brains. Museum visitors, young and old, watch him without blinking, jaws agape, speechless. When one gathers enough courage to ask him what exactly he’s doing, he tells them: He’s practicing real science.

“I think a lot of people today, their whole world is on a computer screen or a TV screen,” Rice explains. “There’s a disconnect with reality. You can’t get more reality than skinning a bird.”

That unpleasant task, it turns out, is a large part of his job as collection manager for the Academy’s Department of Ornithology. Every bird specimen—whether it was collected 200 years ago or just last week—in the Academy’s 200,000-strong collection must undergo this “study-skin” preparation, which ends with the bird being stuffed with cotton.

“The care and maintenance of specimens can seem routine and mundane,” he says. “But we’re caring for some of the most important and historic material ever collected in the New World.”

Many specimens were collected by the two biggest names of 19th-century natural science: Alexander Wilson, the naturalist and illustrator known as the father of American ornithology; and none other than John James Audubon, the famed artist of American birds and mammals.

“We have historically important, cultural specimens here that are still very useful today to scientists and artists,” Rice says. But because of their age, he adds, they have special treatment requirements. “Without care, some of the world’s most important biological material would be destroyed.”

The Academy actively adds specimens to the collection, about 1,000 a year, including hundreds that have been harvested by Rice himself. His work takes him to locations as far-flung as Vietnam, Australia, Paraguay, Poland and Germany, and often, Rice is doing more than just collecting in these areas. On his most recent research trip to Vietnam, for instance, Rice and his colleagues surveyed birds for emerging diseases, particularly avian influenza, which could be transferable to humans.

Next up for Rice is an expedition to Mexico, where he hopes to collect even more specimens and help train young Mexican scientists in the field.

Until then, he’s got a lot of skinning to do.

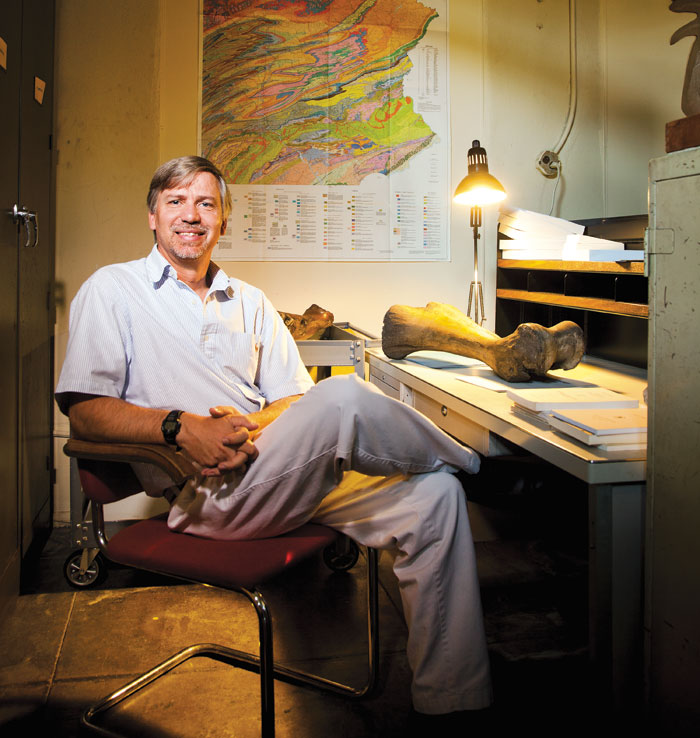

Ted Daeschler, Curator, Vertebrate Paleontology

They say it’s not wise to dwell on the past. But Ted Daeschler lives for it. The past—the very deep past—is his specialty, and he’s the Academy’s go-to guy for all things paleo.

Hand Daeschler a fossil or bone—any size, shape or age—and he can likely tell you the story behind it. It’s what you’d expect from a guy who started his professional career nicknamed “the bone guy.” At the Academy, he wears many hats, including posts as vice president for the Academy’s Center for Systematic Biology and Evolution and curator of the vertebrate paleontology collection. It’s in these roles that Daeschler spends his time looking ahead, focusing on the future and growth of the collection and the department’s research program, all while bringing scientific recognition to the Academy.

Outside of the Academy, Daeschler hunts for signs of prehistoric life. He recently returned from an expedition to the Nunavut Territory of northernmost Canada, where he searched for Late Devonian-age fossils in an area formed by rivers and deltas 380 to 370 million years ago, Daeschler’s favorite “slice of time.”

The unforgiving terrain in that remote region has produced a number of new species over the years, including the much-publicized Tiktaalik roseae, an animal that lived 375 million years ago and represents the key evolutionary transition from fish to the earliest limbed animals. Daeschler says this work addresses questions about the evolution and diversity of life in that environment, as well as the ancient ecosystems that nurtured that life.

The late Devonian time period is relatively understudied, Daeschler says, which leaves plenty of room for scientists to make exciting new finds.

“In paleontology, there are ample opportunities to make discoveries that are completely new to science. It’s really a rewarding part of the work to find new evidence about the history of life,” he says.

Over the next several months, Daeschler will work with his colleagues to inventory and analyze the “beautifully preserved” small fossil fish collected from his latest expedition. While the fossils might not be the largest, most impressive finds Daeschler’s ever brought back from the field, they are a critical part of the big picture, and offer even further understanding of the history of life on Earth.

Colleagues taken hostage and stories of surviving on cow-tongue sandwiches are just some of the details that can be found in field journals.

Clare Flemming, Archivist

When you oversee a collection that includes more than one million items, it can be hard to choose a favorite.

But Academy Archivist Clare Flemming has one: It’s the Academy’s original constitution, handwritten at its founding nearly 200 years ago. On it, carefully and elegantly scribed on yellowed linen paper, are the guidelines of what the Academy would and would not be.

This treasured document is just one item in the sea of extraordinarily rare and historic books, journals, art, artifacts, manuscripts, photographs, and the unique papers and documents that comprise the Academy Archives. Flemming is keeper of them all. And as long as they play by a few simple rules, researchers are welcome to enjoy these remarkable materials.

The archives are precious, Flemming says, and while they do require special treatment, they exist to be used. “We are not doing our job,” she says, “unless we make this material available to researchers.”

“Working in the library is like being a waitress,” she adds. “Researchers look at the ‘menu,’ I bring them their order, and then they dive into their research.”

The Archives are a part of the Academy’s Ewell Sale Stewart Library, which holds over 250,000 volumes dating back to the 1500s. Flemming, who is also presently serving as library director, calls on the work of Sigmund Freud to explain the difference between the two.

“The library is like the ego; it’s the published papers, the public record, what scientists present to the world as authors,” she says. “The archives are the id; it’s a lot of emotions, the true, inner feelings and moods of natural history explorers.”

Those emotions are recorded, for example, in the form of field notes and journals from scientific expeditions. These notes present a more colorful experience of the expedition than published papers, which are more scholarly and buttoned-up in nature. Mood swings, run-ins with warlords, colleagues taken hostage, and stories of surviving on cow-tongue sandwiches are just some of the details that can found in field journals.

In other words, while Archives aid in scientific research and enhance Academy exhibits, they also serve as an extraordinary—and important—record of humankind’s study of the natural world. — By Katie Clark