For decades, the debate raged.

“When,” legislators and citizens asked, “will our state government get out of the business of wholesale purchasing and retailing alcohol?”

Proponents of liquor privatization promised better selection, lower prices, opportunities for

independent businesses and a windfall for state coffers. Opponents called the movement a corporate-backed cash grab that would put state employees out of work, with only short-lived benefits for taxpayers and potentially long-term public health consequences.

We’re talking about Washington, here; but it could easily be Pennsylvania.

Both states have long weighed the pros and cons of their state-run monopoly on alcohol sales amid organized efforts to privatize it.

So when Washington voters finally agreed to sell o state- owned liquor stores and convert to an open market in 2011 — becoming the first “control” state to do so since Prohibition — it behooved Pennsylvanians to pull up a chair, pour a stiff one and see how things turned out.

A few years in, there are signs that Washington’s Initiative 1183 has not gone down as smoothly as promised. A 2014 report in the Seattle Times noted that after liquor sales expanded from 328 state stores to more than 1,400 outlets, the average cost of a liter was 11 percent higher, due to fees the state added to make privatization revenue neutral. The paper also reported that half of the former state stores auctioned o to entrepreneurs closed within two years, crushed by new competition.

Of course, the devil is in the details, and Pennsylvania legislators and voters could structure privatization very differently to avoid Washington’s pitfalls.

But either way, one outcome would likely be the same: a significant increase in urban violence.

NATURAL EXPERIMENT

When Washington passed Initiative 1183, Drexel researcher Loni Philip Tabb saw the perfect opportunity to put her interests in statistics and public policy to work studying the relationship between violent crime and increased alcohol availability.

Tabb is an assistant professor of biostatistics in the Dornsife School of Public Health within the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in math from Drexel and a doctorate in biostatistics from Harvard University.

She specializes in spatial and spatio-temporal statistics, which means she observes not only how data changes within geographic locations, but also how the data may change over time.

“In order to address certain disparities, you need to know where these disparities exist and ultimately where to focus intervention and prevention resources to eliminate them,” she says.

Existing research already showed a correlation between the availability and consumption of alcohol and social and health problems. In her study, Tabb cites studies from as far back as 1983 to as recently as 2010 showing a connection.

Prohibitions Lifted

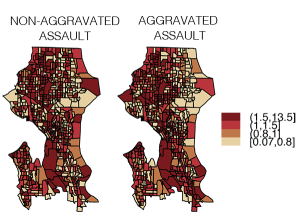

To track the impact of liquor privatization on violence in Seattle, Loni Philip Tabb examined crime data in the city, census block by census block. She compared the data from the two years prior to privatization with the two years afterward, and controlled for a host of variables that are also typically associated with crime. She found a statistically significant uptick in both aggravated and non-aggravated incidents for every additional retail outlet that opened in the city a er 2012. In the maps at right, anything above a “1” indicates an area where an excess risk of assault exists.

To track the impact of liquor privatization on violence in Seattle, Loni Philip Tabb examined crime data in the city, census block by census block. She compared the data from the two years prior to privatization with the two years afterward, and controlled for a host of variables that are also typically associated with crime. She found a statistically significant uptick in both aggravated and non-aggravated incidents for every additional retail outlet that opened in the city a er 2012. In the maps at right, anything above a “1” indicates an area where an excess risk of assault exists.

Tabb herself has previously studied how liquor privatization could potentially affect Philadelphia, in a 2012 paper published with five co-authors in BMC Public Health. The team used geospatial analysis to map existing alcohol retail outlets throughout the city, including bars and restaurants where alcohol is sold for on-premise consumption, and retailers that sell alcohol to be consumed off-premise, such as state-owned wine and spirits stores and small groceries, pizza shops and bodegas that sell beer.

They noticed that crime rates tended to be higher around off-premise retailers where individuals may be purchasing alcohol to consume nearby, such as in a vacant lot or at home.

Then they asked what this might mean for Philadelphia if the city privatized alcohol sales. They found that Philadelphia’s zoning rules, which restrict alcohol retailers near schools, playgrounds and places of worship, could accommodate an additional 60 percent more outlets, or 1,115 more citywide, bringing with them all the “negative health, crime and quality of life outcomes that accompany such an increase.”

For her latest exploration of the subject, Tabb endeavored to avoid the cross-sectional approach of previous studies and instead do a longitudinal analysis, tracking a real-life situation over time — an approach that is more rigorous in pointing toward causation.

“We said, ‘Let’s try and find an area in the United States where they actually implemented some sort of policy that affects alcohol sales and see what happened,’” she explains.

Although a few states — Washington among them — have recently relaxed laws governing marijuana sales and consumption, “with alcohol, it’s not like you have states that go through this all the time, so Washington was perfect,” Tabb says.

SMOKING GUN

Tabb began the study with the hypothesis that increased availability of alcohol would result in more violence in the areas affected.

To test her hunch, she acquired data on aggravated and non-aggravated violent crimes from the Seattle Police Department, broken down by small census blocks, and compared it with liquor licensing records from the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board.

She also collected 2010 census data that she used to control for variables often correlated with local crime, such as a neighborhood’s percentage of vacant housing units, households that were low-income and/or headed by a single female, residents age 15 to 29, density of bus stops and “risky” retail outlets, and broader indicators of racial and ethnic diversity.

“The nice thing about being in a big data environment is you’re able to access data through various settings,” she says.

With a wealth of information available, Tabb was able to compare the rates of violence in each census block group within Seattle for both the two years prior to privatization and the two years after it went into effect in 2012.

In Seattle overall, aggravated assaults increased 42 percent and non-aggravated assaults increased 74 percent between 2010 and 2013, the period overlapping the state’s transition to an open alcohol market.

The data revealed an unmistakable smoking gun. Aggravated assaults, which are typically those involving a weapon with an intent to cause bodily harm, increased 8 percent for each additional off-premises outlet in a given neighborhood, and 5 percent for each additional on-premises outlet. The rate of non-aggravated assaults also increased, by 6 percent and 5 percent for each type of retailer respectively.

In Seattle overall, aggravated assaults increased 42 percent and non-aggravated assaults increased 74 percent between 2010 and 2013, the period overlapping the state’s transition to an open alcohol market.

South-central Seattle, the northwestern portion, and some blocks on the eastern border bore the brunt of the worsening violence. Although the use of aggregate data, as Tabb used in her study,unintentionally lends itself to a research problem known as the ecological fallacy, which involves drawing conclusions about individuals based on analyses involving neighborhood-level data, her study sheds light on the various relationships that exist at the neighborhood level that can’t be ignored.

“The more alcohol available in a neighborhood, the tendency there is for more violence,” she says. “Since this policy allows for increases in sales and ultimately availability in these neighborhoods, we’ll likely see more violence in these neighborhoods as well.”

Washington attempted to head o this problem by requiring new off-premises outlets to be large retailers, such as supermarkets and warehouse stores. This was a direct attempt to avoid more liquor sales in corner stores and bodegas in already-disadvantaged neighborhoods. Such factors could be considered in Pennsylvania if the state were to approve privatization, for the very same reasons, Tabb says.

Liquor Limits

Seventeen states, plus small jurisdictions within Alaska, Maryland, Minnesota and South Dakota, control alcohol sales or wholesaling in some form. They control the sale of distilled spirits and, in some cases, wine through government agencies at the wholesale level. Thirteen of those jurisdictions also exercise control over retail sales for off-premises consumption; either through government-operated package stores or designated agents.

Seventeen states, plus small jurisdictions within Alaska, Maryland, Minnesota and South Dakota, control alcohol sales or wholesaling in some form. They control the sale of distilled spirits and, in some cases, wine through government agencies at the wholesale level. Thirteen of those jurisdictions also exercise control over retail sales for off-premises consumption; either through government-operated package stores or designated agents.

“Philly has a stronger relationship between alcohol and violence [than Seattle],” Tabb says. “Smaller stores are selling alcohol in neighborhoods that are even more disadvantaged than in Seattle.”

She theorizes that on-premises alcohol retailers attract less violence crime because they self-police. While “bar districts” such as Philadelphia’s Old City see issues with drinkers becom- ing unruly or getting into ghts after leaving bars, the managers of those bars and restaurants are much more likely to step in and take control of the situation as a group, Tabb notes.

“They have a real vested interest in setting up a neighborhood where their customers are safe,” she says.

“I think if you’re going to have an additional [wine and liquor] outlet, I’d prefer that it be at a BJ’s rather than an [urban] mom-and-pop store that’s going to potentially attract other risky behavior often associated with alcohol and violence,” she says.

With Philadelphia capable of hosting as many as 1,115 additional alcohol outlets should privatization ever go through, Tabb says she hopes her study helps further inform the liquor privatization debate in Pennsylvania.

“I know for Philadelphia, there’s going to be a significant impact with respect to privatization,” she says. “There will be a substantial uptick in alcohol outlets, and we need to make sure there are policies in place that address the potential complications.”

“This kind of study is very useful for policy,” says Andrew Lawson, a distinguished professor at the Medical University of South Carolina who is also founding chief editor of Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology, the Elsevier journal where Tabb’s study is under review. “Public health departments need to make decisions all the time about whether there is risk in a certain geographic area, like in the case of environmental pollution from toxic waste dumps or incineration sites. These are known as ‘cluster alarms’ in the public health literature and health departments get them every day from people claiming that there is some adverse health risk in their neighborhood. The methods used by Dr. Tabb are used widely in those investigations.”

LAST CALL

Lore has it that Pennsylvania Gov. Gi ord Pinchot created the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board in 1933, just as Prohibition came to an end, expressly to “discourage the purchase of alcoholic beverages by making it as inconvenient and expensive as possible.”

That pretty much sums up the experience Pennsylvania drinkers have dealt with ever since.

The PLCB’s rules and stores have become more consumer- friendly in recent years and, at press time, Pennsylvania passed a new law that will soon allow gas stations, grocers and hotels to sell take-out wine and beer. But up until this recent law change, the system has restricted liquor and wine sales to state-owned stores and beer sales to distributors and to bars or grocery stores with special licenses. For a long time, Sunday retail hours at state-owned stores were restricted, and bars weren’t allowed to offer happy-hour specials for more than two hours per day.

Pennsylvania also adds a hefty tax to every bottle, courtesy of a supposedly temporary 10 percent tax instated in 1936 to help rebuild Johnstown after one of its many foods. The mining town was eventually rebuilt, but the tax was never repealed. Instead, Pennsylvania increased it — to 18 percent, where it generates $334 million for the state treasury but also contributes to high prices and a perennial chorus of voices demanding change.

Among the policymakers and in uencers who have staked out positions in the liquor privatization debate, the lines are drawn almost indelibly.

Against privatization are the unions and their members — particularly the approximately 4,500 state workers who staff the state-owned wine and spirits stores — as well as the Democratic lawmakers who depend on their support.

“The people who champion the privatization of liquor stores promise better prices and no change in the current rates of crime or alcoholism, but their argument is a Trojan horse,” says State Sen. Anthony Hardy Williams, a Democrat whose district includes Philadelphia and Delaware counties. “The Washington state study proves there are increases in both when there is greater access to alcohol. That greatly concerns me, and it should greatly concern most people who value community and a good quality of life.”

And even though beer distributors are private enterprises licensed by the state, privatization would likely also negatively impact their business, just as Washington liquor retailers discovered when they suddenly got more competition from other outlets than many could handle.

“Eighty to 90 percent of our income comes from beer sales,” Mark Tanczos, president of the Malt Beverage Distributors Association of Pennsylvania, told the Harrisburg Patriot-News. “How are we going to be making a living if everyone has it?”

Those in favor of privatization are represented by an almost exclusively Republican coalition that promises that a state-licensed private enterprise system would provide convenience and choice at lower prices, plus more tax revenue from additional stores.

“Other states do this and the world has not fallen apart there, unless you’re assuming that Pennsylvanians and Washingtonians are unique in some way,” says State Rep. Kate Harper, who supports privatization.

The Montgomery County Republican says she sees the results of Tabb’s study as being potentially helpful in setting zoning limits for new retailers under liquor privatization.

However, she’s troubled by the notion that disadvantaged neighborhoods might receive limited access to alcohol because of the potential for violence.

“To pick out people in a neighborhood and say, ‘Sorry, Prohibition still applies to you,’ I don’t think that’s fair,” she says. “I think it’s completely inappropriate for government to set socioeconomic limits on the consumption of alcohol.”

That said, with Gov. Tom Wolf ’s veto of the latest privatization bill in July of last year, Harper expects other, more urgent state issues to take precedence, such as the state’s budget.

“I’ve voted for [privatization] twice now,” she says. “It’s not the biggest issue for my constituents or on my agenda.”

For Tabb’s part, she wants to make sure those who are in positions to decide the matter have all of the facts at their disposal.

“Being here and knowing that it’s something that is probably going to be implemented in my lifetime, I thought it was necessary to continue to build the evidence,” she says. “I like to think that policymakers try to find the information that’s out there with respect to how neighborhoods function. My role is to conduct sound research that allows for an evaluation and assessment of these complex relationships.”