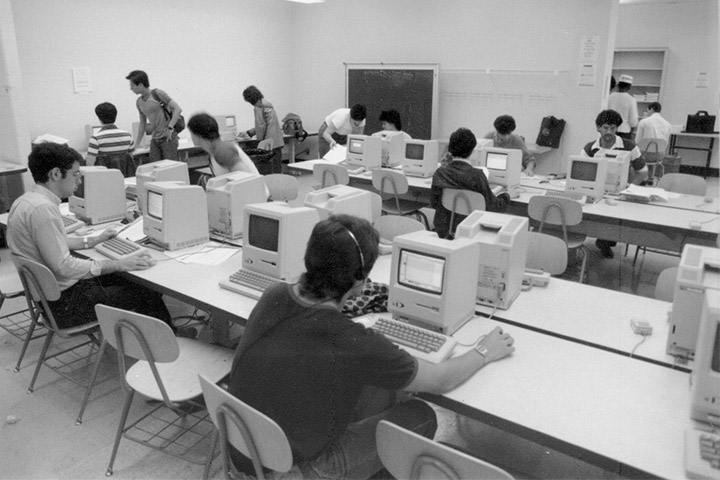

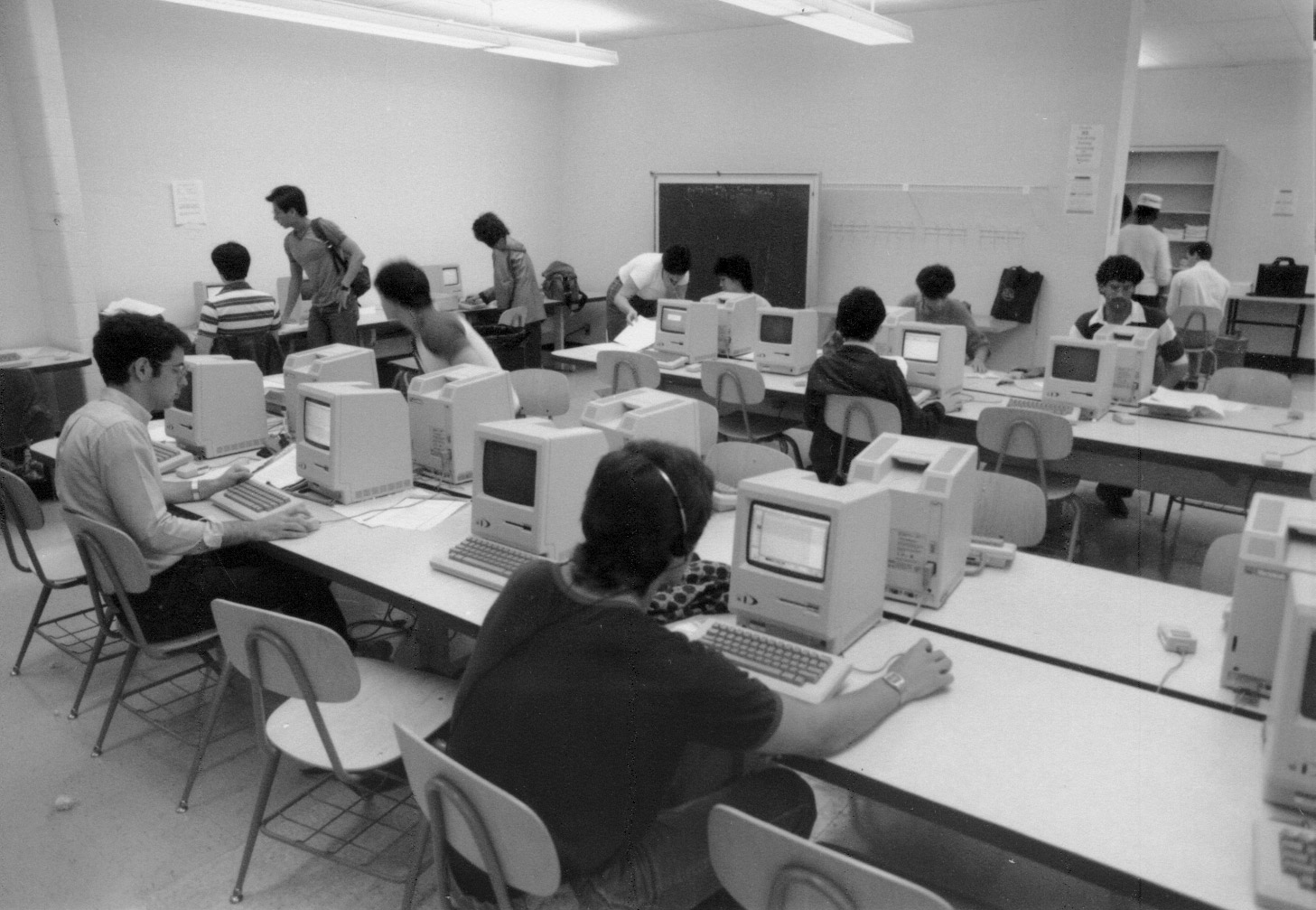

Photo courtesy of Drexel University Archives

In the early 1980s, Drexel’s Microcomputing Program revolutionized higher education by requiring all incoming students to use a desktop computer, launching the national rollout of Apple’s revolutionary new Macintosh model.

In 1984, personal computing was in its infancy. Hardly any households had a computer, and hardly anyone brought one to college. Taking a bold risk, and partnering with the young Apple Computer Inc. to supply students with the company’s Macintosh machines, Drexel became the first university in the nation to require that all incoming students have a personal computer (see the full story of how Drexel geared up for the computer generation).

Looking toward a future 21st century, Drexel’s then-president William W. Hagerty declared, “In every field, the successful practitioner will utilize computer technology to understand and deal with the challenges of everyday life.” Dubbed Drexel’s Microcomputing Program, it was a visionary initiative that embodied Drexel’s tradition of anticipating the needs of a changing world, a value that continues to shape a Drexel education today.

Youngmoo Kim, vice provost of university and community partnerships, highlighted this pivotal moment in Drexel history as he introduced the speakers during a TED Talk–style event during Alumni Weekend 2024 titled, “The Apple Legacy: Drexel’s Innovation in Education.”

“In 1984, Drexel saw that everyone would need a computer and technology skills,” he remarked. “Today, we’re still committed to digital equity and are leading efforts to ensure that everyone has access to technology, training and education.”

Connecting past and present, he added that this pioneering spirit continues to evolve and deepen at Drexel, in ways that go beyond technology. “Innovation drives our commitment to community and society,” he says. “At Drexel, we also apply innovative process, build on our collective knowledge, and put it to use in our local communities and for society at large.”

Here we’ve highlighted remarks from some of the faculty who spoke at the event about how their work exemplifies innovation in education at Drexel.

Top Right: Helen Teng, associate clinical professor; Bottom Left: Kate Morse, assistant dean for experiential learning and innovation and associate clinical professor.

Preparing for Disaster

In her talk, “Preparing for Disaster,” Kate Morse, assistant dean for experiential learning and innovation and associate clinical professor, and Helen Teng, assistant clinical professor, both from the College of Nursing and Health Professions (CHNP), shared how Drexel uses simulations to prepare nursing students for unexpected situations.

Central to a CHNP education is time logged in the Center of Interprofessional Clinical Simulation and Practice. It’s an 18,000-square-foot facility equipped with skills labs, operating theaters, hospital rooms, high-fidelity mannequins and access to live actor-patients, all designed to allow students to practice patient care and a range of care-delivery and disaster simulations in realistic settings.

Sharing an example, Teng introduced a disaster scenario about a nurse working at a large urban hospital. She asked the audience to imagine that a state of emergency has been declared, and the public is told to stay home. Hospitals are expecting large numbers of patients exhibiting symptoms of unknown origin. The nurse is anxious but becomes focused on the work at hand, harnessing the skills learned through Drexel’s intensive simulation training.

This example is reminiscent of the early days of COVID-19, but the forward-looking CNHP has been training students through this sort of disaster simulation since even before the pandemic. “Even in high-stress environments, students learn to methodically assess patients, note symptoms, and develop nursing care plans,” Teng shared. “They leave the experience feeling more confident in their clinical decision-making.”

In this area, Drexel stands apart from its peers, said Morse. “Simulation has become woven into curricula across the country, but Drexel has a remarkable physical capacity now because of the Center. We’re also able to plan interprofessional simulations with our College of Medicine colleagues, which is important for learning how to work in teams.

Steve Vásquez Dolph, associate teaching professor of Spanish and associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion.

Learning from the Land

In the final presentation of “The Apple Legacy” event, Steve Vásquez Dolph, associate teaching professor of Spanish and associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion, spoke about a community-based learning course he teaches called “Food and Land Security in Philadelphia.” The course, sponsored by the Lindy Center for Civic Engagement and the Writers Room UnMapping Project, examines the causes of the food crisis in Philadelphia. It looks at food access through a social justice lens, and his students work with local agricultural organizations addressing these issues.

Dolph’s program doesn’t apply a technological solution to a problem in the conventional sense. However, culture is the fundamental technology of a just food system. And Dolph’s approach to community-based teaching and learning exemplifies Drexel’s innovation in educational process, experiential learning and providing students with immersive experiences to be part of a solution.

Describing the issue, Dolph said, “In Philadelphia, one in six families is food insecure, and for children, it’s closer to one in three. Food insecurity is linked to historical segregation, disinvestment and was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The framework of the “Food and Land Security” course centers upon “milpa,” an ancient system of agriculture using corn, beans and squash — known as the Three Sisters of traditional farming. Dolph explained, “Indigenous people have long used these crops to create sustainable food systems and to organize social structure and religious practice. In this course, we translate ‘milpa’ into an educational system. Our work is collaborative, it engages ancestral knowledge, and more than anything, it’s community-based and land-based.”

Dolph’s students engage directly with community agricultural projects in Black and Latinx neighborhoods in Philadelphia, studying foods like purple hull peas and okra and practicing seed keeping. They are encouraged to consider the work as sacred and an act of cultural preservation. Dolph explained, “Food work is about engaging in a reverential relationship with each other and with the land. Students participate in this work as a kind of social justice practiced by growers, promoters and policymakers here in our city.

Detecting Deepfakes

Matthew Stamm, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering, spoke on “Detecting Deepfakes,” in which he discussed the tools he and his team at Drexel’s Multimedia and Information Security Lab have developed to detect manipulated media.

“Watching the news, it’s apparent that there are new information security challenges created by fake, manipulated and AI-generated images and video, and increasingly audio,” he warned. “They’re being used in political campaigns and to commit fraud and cybercrime.”

Stamm’s lab is leading the way in developing techniques called multimedia forensics that identify these deepfakes. “We use the fundamental precept of traditional forensics, that every contact leaves a trace, like a criminal leaving fingerprints at a crime scene,” he explained. “Multimedia forensic algorithms search for traces left by the generative AI or editing operations used to create or modify an image, video or audio file.”

Using a special type of neural network pioneered by his lab, Stamm is able to break up an image into little pieces and find forensic traces in each piece. “Our tool can identify the editing techniques used to falsify images and videos,” he said. “We’ve created these tools for the U.S. Department of Defense, and they’re being distributed throughout the U.S. government.”

The work of Drexel’s Multimedia and Information Security Lab is constantly evolving and advancing; even so, Stamm acknowledges the limits of technology. He concluded his talk saying, “We can’t solve this problem entirely by technology; it’s fundamentally a human problem. We need contributions from law, public policy, psychology, communication, philosophy and ethics. Here at Drexel, we have scholars from multiple fields looking at this problem from multidisciplinary perspectives.

Help ensure today’s students have access to cutting-edge innovation, advanced technology and expert faculty by visiting giving.drexel.edu/Advance. Your contribution can make a transformative difference in their education and future success!