In 2012, an amateur paleontologist hunting for shark teeth in a brook in Monmouth County, N.J., noticed a bone fossil lying on a grassy embankment.

“I picked it up and thought it was a rock at first — it was heavy,” says Gregory Harpel, an analytical chemist from Oreland, Pa.

Watch as two fossils discovered a century and a half apart are reunited by scientists from the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University

The surprising puzzle assembly linked scientists from both museums to their predecessors from the 19th century, while setting the stage to advance science today.

Harpel brought the bone to Jason Schein, assistant curator of natural history at the New Jersey State Museum, who along with David Parris, the museum’s curator of natural history, recognized the fossil as a humerus — the large upper arm bone — from a turtle, but its shaft was broken so that only the distal end, or end nearest to the elbow, remained.

Parris joked with Schein that perhaps it was the missing half of a different large, partial turtle limb housed in the collections at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. The bone in the Academy’s collection was also broken at the shaft, on the opposite end. The coincidence was striking.

When Schein brought Harpel’s fossil to the Academy, sure enough, the bones matched.

“As soon as those two halves came together, like puzzle pieces, you knew it,” says Ted Daeschler, associate curator of vertebrate zoology and vice president for collections at the Academy.

“I didn’t think there was any chance in the world they would actually fit,” Schein says. He believed that the Academy’s piece of the puzzle was much too old, and the conventional wisdom shared by paleontologists is that fossils found in exposed strata of rock will break down from exposure to the elements if they aren’t collected and preserved, at least within a few years — or decades at the most.

There was no reason to think a lost half of the same old bone would survive, intact and exposed, in a New Jersey streambed from at least the time of the old bone’s first scientific description in 1849, until Harpel found it in 2012.

The Academy’s older bone was also unique, making a perfect match seem even more unlikely. It was originally named and described by famed 19th-century naturalist Louis Agassiz as the first, or type specimen, of its genus and species, Atlantochelys mortoni. In the intervening years, it remained the only known fossil specimen from that genus and species.

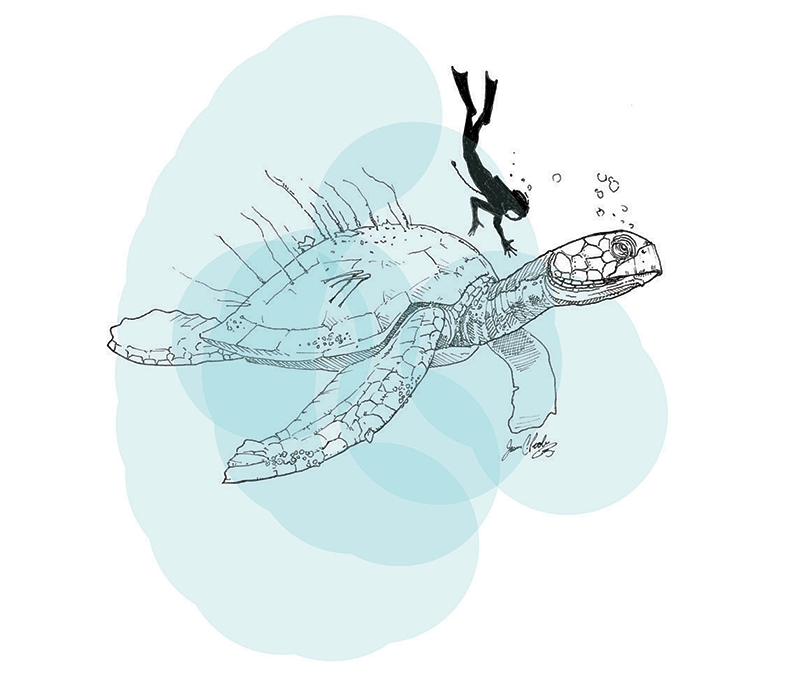

Paleontologists calculate the animal’s overall size to be about 10 feet from tip to tail, making it one of the largest sea turtles ever known. This illustration suggests the difference in scale between the turtle and a human.

It remained so until that fateful day when Schein carried the “new” New Jersey fossil to the Academy, where Academy paleontology staffers Jason Poole and Ned Gilmore connected the two halves. The perfect fit between the fossils left little space for doubt. Stunned by the implications, Schein and staffers called Daeschler into the room.

“Sure enough, you have two halves of the same bone, the same individual of this giant sea turtle,” says Daeschler. “One half was collected at least 162 years before the other half.”

Now, the scientists are revising conventional wisdom: Exposed fossils can survive longer than previously thought. They report their remarkable discovery in the forthcoming 2014 issue of the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences. The find was also featured in the April 2014 issue of National Geographic magazine.

“The astounding confluence of events that had to have happened for this to be true is just unbelievable, and probably completely unprecedented in paleontology,” says Schein.

The fully assembled A. mortoni humerus now gives the scientists more information about the massive sea turtle it came from, as well. With a complete limb, they have calculated the animal’s overall size — about 10 feet from tip to tail, making it one of the largest sea turtles ever known. The species may have resembled modern loggerhead turtles, but was much larger than any sea turtle species alive today.

The scientists believe that the entire unbroken bone was originally embedded in sediment during the Cretaceous Period, 70 to 75 million years ago, when the turtle lived and died. Those sediments eventually eroded and the bone fractured millions of years later during the Pleistocene or Holocene, before the bone pieces became embedded in sediments and protected from further deterioration for perhaps a few thousand more years until their discovery.