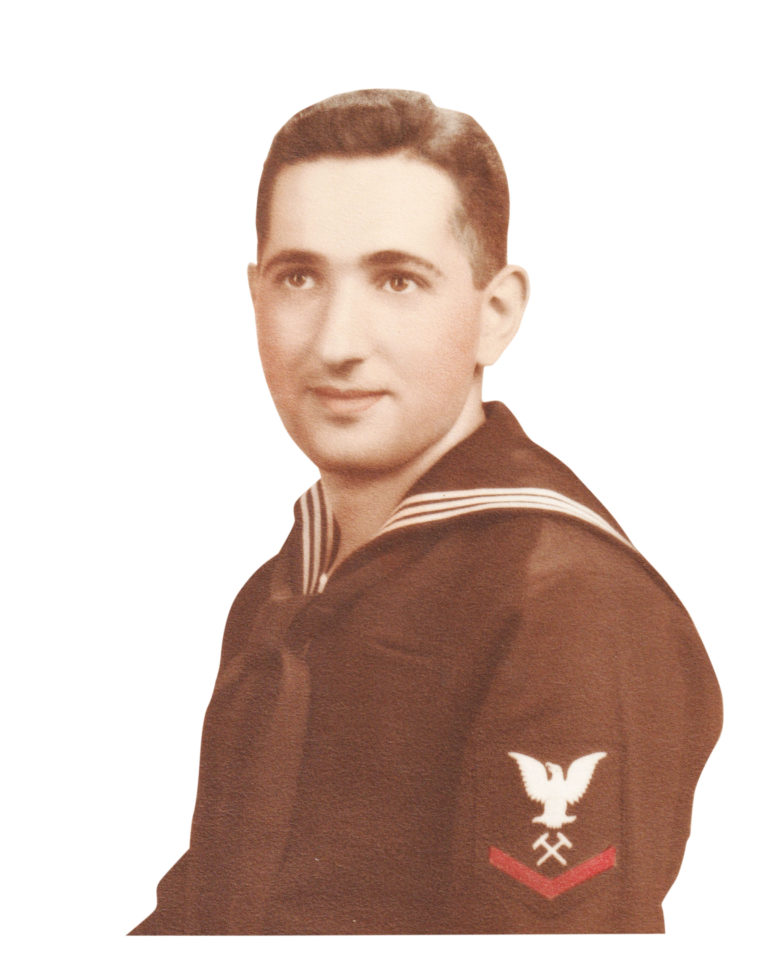

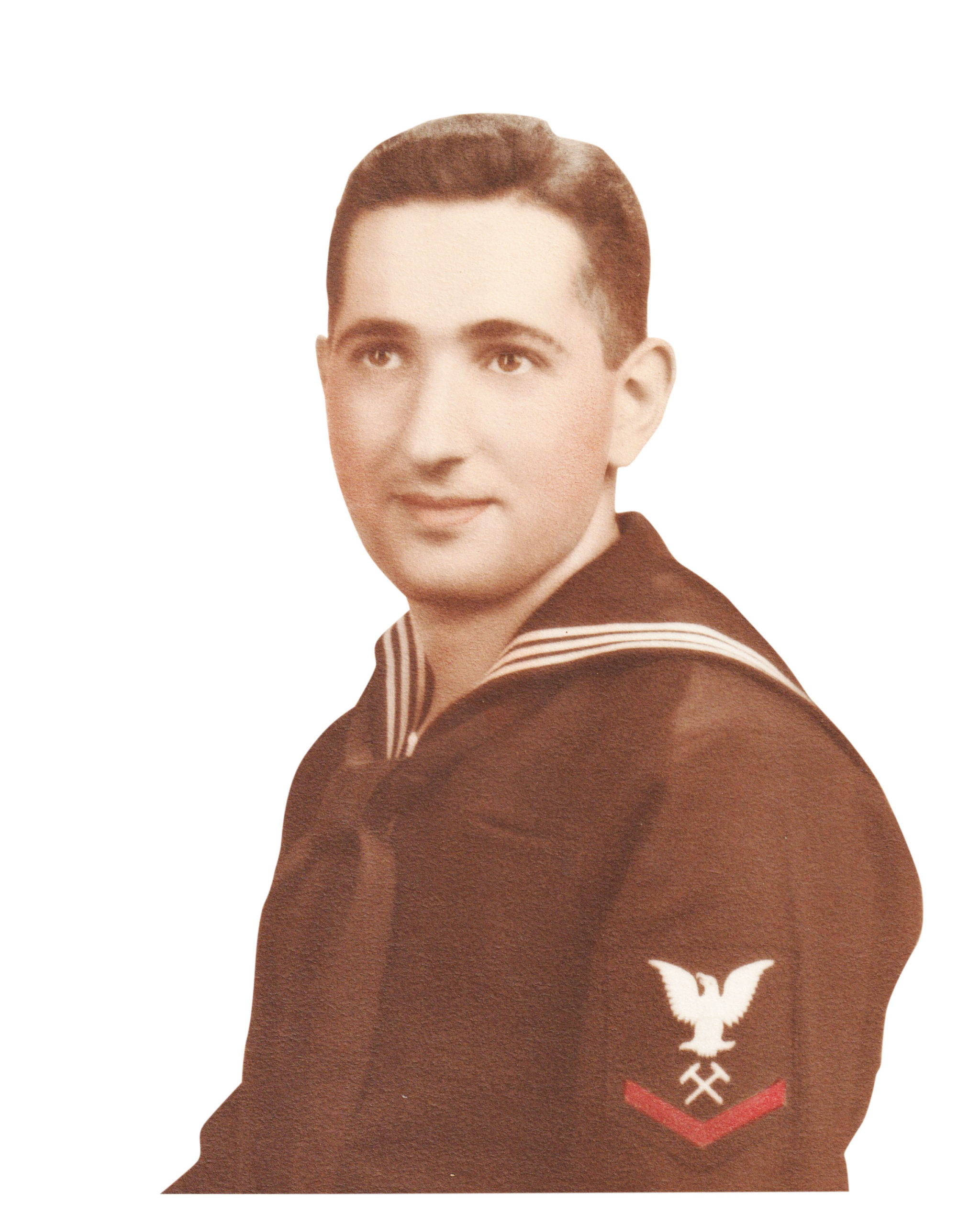

Harold Naidoff’s U.S. Navy portrait.

Harold Naidoff was a World War II veteran co-oping as a coppersmith at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard when he fell victim to one of the more divisive eras in American politics. He was suspended and ultimately fired from his co-op because of his supposed ties to an organization deemed “subversive.”

After Harold Naidoff ’53 died in 2005, his children saw for themselves what had transpired half a century earlier. Bruce Naidoff, Bobbie Lewis and Susan Holliday found, in a box of their father’s belongings, the legal transcript of a 72-minute hearing at the Pentagon in which the then 29-year-old mechanical engineering major appealed the Navy’s suspension.

Naidoff, then a married father of two, had attended four meetings organized by the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order, a section of the International Workers Order (IWO) that he said he joined for the insurance coverage it provided its 180,000 members. But the Navy claimed, without evidence, that in 1940, Communist Party nomination petitions had been signed by Naidoff’s wife (before he met her) and his father (when he was a minor).

Several times during his appeal hearing Naidoff was asked to defend his Jewish identity as well as his participation with the Jewish People’s Fraternal Order. He told investigators: “…Since the war, especially the war with Germany, I realized any organization that could help better the culture and the ideas of the Jewish people would be an organization with which I would be glad to be considered a member, especially if that organization was in a way democratic and upheld the ideas of this country.”

His attestations of loyalty didn’t save his job, however. The U.S. Navy fired Naidoff, and he worried that Drexel would expel him.

Naidoff’s children told Drexel Magazine, “Though we all knew this story from our father’s past, the details were new and the harsh tone of the charges in the transcript were startling. Our parents weren’t bitter about the episode and it didn’t seem to harm our dad’s career. But the transcript laid out the difficulties he had to go through as a young man and how he honorably fought the false charges. And Drexel stood behind him when he most needed the support, for which we’re grateful.”

Back on Drexel’s campus, Naidoff was assured by his co-op coordinator, department head, College of Engineering dean and even by the president of the Drexel Institute of Technology, James Creese at the time, that he wouldn’t suffer any professional or educational setbacks at Drexel.

“The president of Drexel Institute informed me even though I have been suspended from the naval shipyard I am a student of Drexel in good standing and, as such, the school would do everything they could to help me,” Naidoff testified. “And he suggested if I felt that the decision was adverse to me I should fight it to the utmost, and I decided to do so.”

Naidoff didn’t want his Navy job back, but he did want to clear the charges against him. Unfortunately, that never happened. Naidoff became one of the federal workers who lost their jobs during the Truman purges of supposed communist infiltrators, in which reportedly between 3 and 4 million were investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigations.

Luckily, Naidoff was able to find a new, higher-paying co-op in the private sector within a day of his suspension. After graduating from Drexel, he continued working as an engineer, later migrating into the sales and marketing side. A tennis player for the ’48, ’50 and ’53 Drexel tennis teams, Naidoff remained friends with Drexel’s tennis coach, Dave Perchonock, for years and continued playing tennis until his ‘70s.

Naidoff never forgot how Drexel had supported him in his time of need. For the rest of his life, he was a regular donor to the University, the Athletics Department and the College of Engineering.

“We were small children, or not even born yet, when this happened, so for young people today this may be ancient history,” says Naidoff’s children. “It’s important for everyone to realize what can happen here if we aren’t vigilant about safeguarding our rights.”