Brittany Jackson ’19 completed her Pennsylvania teaching certification in middle school math at Drexel while apprenticing at Albert M. Greenfield Elementary in Philadelphia in 2018. The experienced equipped her to teach math in her own classroom at Hill-Freedman World Academy starting in fall 2019.

It’s late September 2018 and a new school year is underway at Albert M. Greenfield Elementary in Philadelphia’s Fitler Square neighborhood. Inside Room 309, math teacher Jessica Charmont teaches linear equations, functions and algebra to her class of eighth graders. She also has a much more grown-up pupil in class today: 27-year-old Brittany Jackson, a Drexel University School of Education graduate student working toward her Pennsylvania teaching certification in middle school math.

Jackson will spend the academic year shadowing Charmont, learning from the seasoned instructor how to be an exceptional public school teacher. Jackson is part of a small cohort of School of Education grad students participating in the Philadelphia Teacher Residency (PTR) program, a full-time teacher-certification program aimed at producing well-prepared educators, with a current focus on math and science educators, to teach in the city’s public schools.

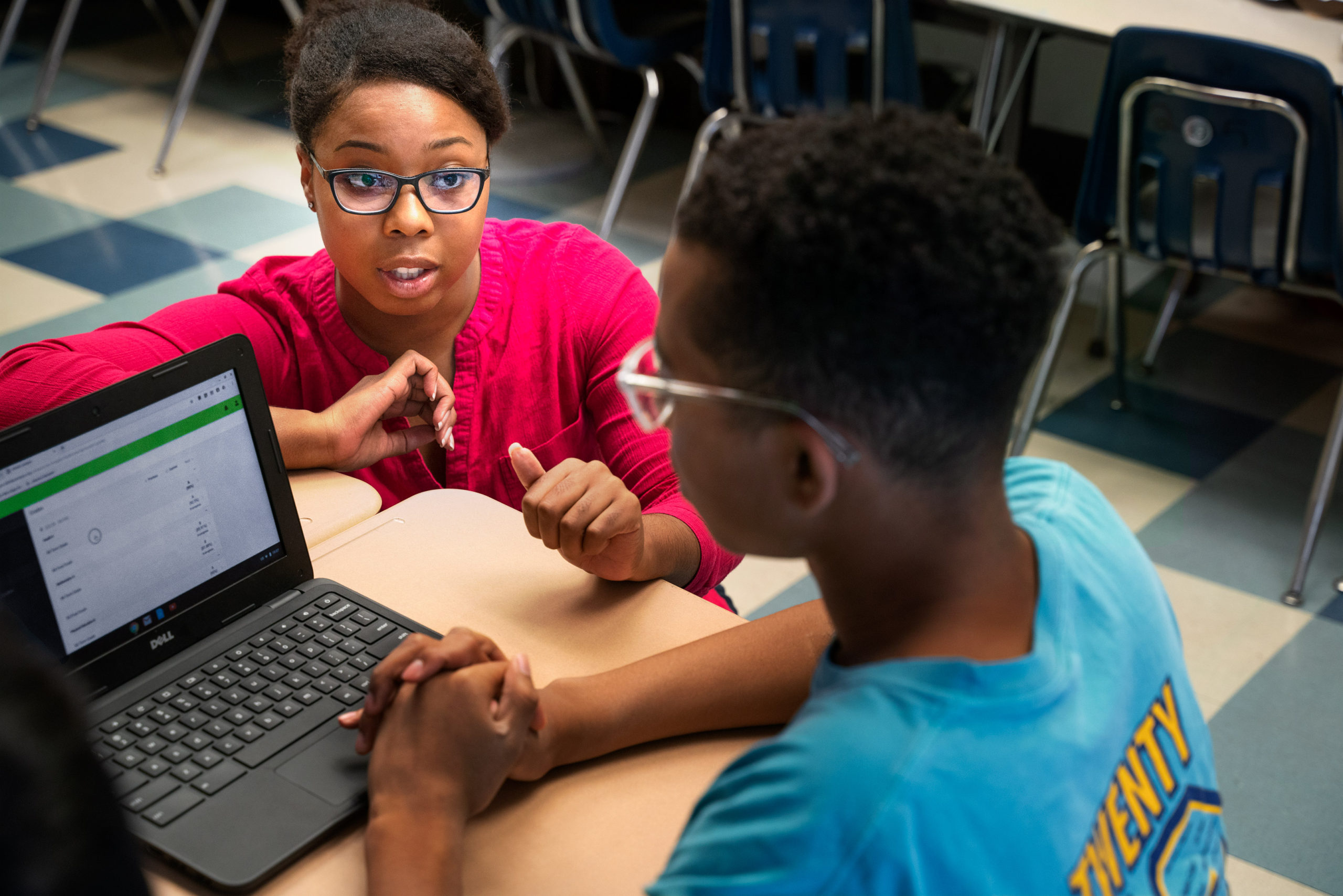

Today, Jackson is looking over Charmont’s shoulder at her laptop as they plan the day’s lessons. The two chat about upcoming conferences and workshops and geek out about the class’ TI-Nspire calculators. They go over concerns like timing and when to introduce new concepts to the class, and they share some laughs along the way. Then the bell rings, signaling the start of class.

“Log in, have a seat, notebooks out, pencils out,” Charmont bellows, now all business.

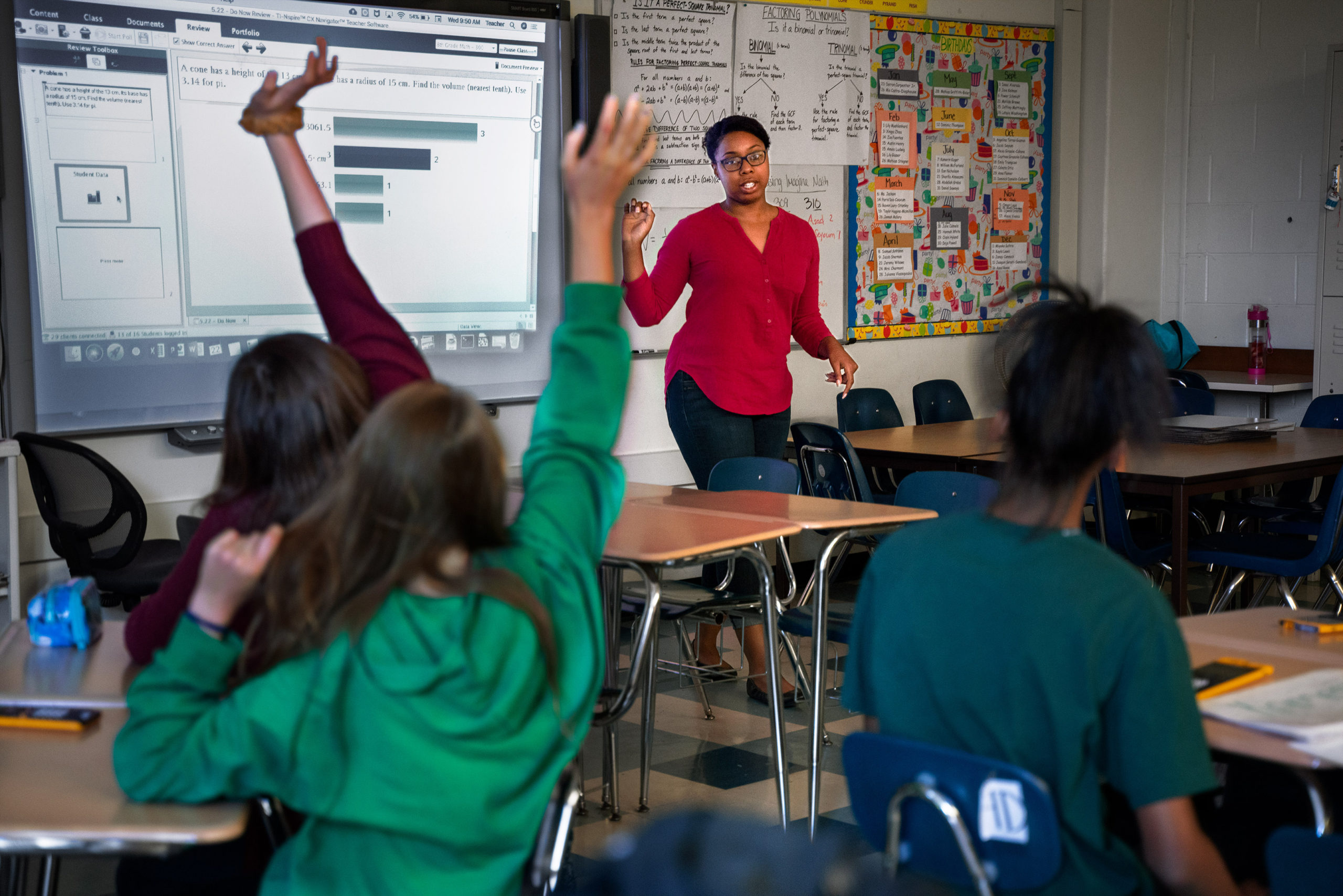

Charmont and the class get right into solving equations. Students submit answers on their calculators and a breakdown of their responses appears on an interactive Smartboard screen at the front of the room. The class is fast-paced and technology driven. At times, Charmont gives the students just 10 seconds to solve an equation. Then, with the press of a button, she can slow everything down.

Brittany Jackson ’19

“Ha! I have control!” she jokes as she halts the algebra lesson. “I can pause you whenever I want!”

From the back of the classroom, Jackson is settling pods of students. She takes a seat in the back once the class has reached its groove.

“I’m not used to standing all day,” she whispers exhaustedly, out of earshot of the students.

But for Jackson, being on her feet all day is a small price to pay. She always wanted to teach, but after earning a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Rutgers University, she found it would be too difficult to also earn her certification as it would mean going back to school and picking up another degree in education. She fell into a series of customer service and finance positions, but the PTR program allowed her to change lanes toward the career she’s always wanted.

She’s already been doing some grading and working one-on-one and in small groups with students, but soon she will move from observer to active teacher.

“I think that being able to kind of sit back and see what’s happening while students are learning gives me a lot of insight in how to engage students and react to different behaviors,” Jackson says. “I just announced my takeover to two of the classes, and I want them to know that they’re integral to my learning — I’m learning from them and they’re learning from me.”

Class Experiments

School districts around the country are experimenting with teacher residency models like the one recently adopted in Philadelphia in hopes of improving their teacher pipelines.

One of the first districts to adopt the model was Chicago in 2001, followed by Boston and Denver in 2003. More recently, in May the Dallas Independent School District pledged $19 million in funding for three teacher residency programs to train as many as 500 candidates within five years. About 80 to 100 residency programs operate nationwide, estimates Barbara McKenna, spokesperson for the California-based advocacy organization Learning Policy Institute.

Resident teachers are graduate-level college students who apprentice with an experienced teacher for a year of “residency” inside a public school while enrolled in coursework with a partner university, sometimes with a salary, stipend or tuition waiver. After earning their teaching credentials, they commit to work in the district for several years.

In Philadelphia, Drexel participants receive 50 percent off their tuition rate as compared to the baseline graduate student rate, plus a salary (currently $38,611) and benefits from the School District of Philadelphia, as well as a scholarship that covers 75 percent of the already discounted tuition. Both institutions are making an investment in this model to make the transition to the teaching workforce more affordable for participants.

“Nationally, there’s a teacher shortage that a lot of districts and organizations are trying to find actionable solutions to,” says Chanell Bates, director of strategy and operations for the School District of Philadelphia’s Office of Talent Support Services. “Teacher residency programs are typically cited as a great path toward addressing teacher shortages. So…the School District of Philadelphia started to think through what it would mean to create a version of it for ourselves.”

Although research is still emerging, proponents contend that teacher residency programs produce educators who are better prepared and compensated, as well as less burdened by student debt — plus, hopefully, happier with their career choice.

Ill-prepared teachers are two to three times more likely to leave the profession after their first year than teachers with comprehensive preparation, according to the Learning Policy Institute. Moreover, the Institute reports, “research shows that the more debt college students incur, the less likely they are to choose to work in a lower-wage profession like teaching.”

In 2016–2017, the National Center for Teacher Residencies, a Chicago-based organization which assists a network of high-performing residency programs, surveyed 73 principals and 199 graduates involved in residency programs. The NCTR found that 91 percent of the principals agreed that residents outperform teachers prepared through other pathways, and 95 percent of the graduates said they believed they entered the classroom with more effective skills than the average new teacher.

In addition to Drexel, Philadelphia’s program draws graduate education students from the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University and Relay/GSE, the latter of which was the school district’s sole partner when it launched the PTR program in 2017. Each future educator pledges to teach math, science, English or Spanish in the district’s middle or high schools for at least three years following graduation. Drexel PTR students are all focused on filling this STEM pipeline.

That can make a difference in subjects in which teacher vacancies are high. Forty-three states including Pennsylvania reported teacher shortages in math and science subjects for the 2017–2018 school year to the U.S. Department of Education.

“Just imagine what it would be like to never have a physics teacher,” says Bates. “[That’s the case] in some areas of the city, and it’s a pervasive problem. We are hoping that though the short-term cost of PTR is high…the short-term benefit is that we have fewer vacant positions, and the long-term benefit is that we get teachers who are committed to the district.”

Some form of residency program has existed at Drexel since 2013, but the 2018–2019 school year was the first time Drexel entered the formal partnership with the School District of Philadelphia. Since then, Drexel PTR students have maintained an 86 percent retention rate and have achieved a 100 percent hiring rate within the school district.

For Jackson, the district’s salary and tuition coverage sealed the deal.

“I really couldn’t think of a better program to be a part of,” she says. “And I would not be having this experience without [compensation] because I have bills to pay. There’s no way I could do what I’m doing and have a different job [on the side].”

Math Problems

The time and capital invested in teacher residents is the School District of Philadelphia “putting their money where their mouth is,” according to Sarah Ulrich, associate dean of Teacher Education and Undergraduate Affairs for Drexel’s School of Education. “Philadelphia is one of the few large districts that’s really investing that much in the residency model.”

The program attracts individuals from a variety of backgrounds, but they all have one thing in common, she says. “Our most successful students are truly committed to teaching. They really want to be in Philadelphia and invest in Philadelphia and grow roots in Philadelphia and establish their careers in Philadelphia.”

“When we look at the backgrounds of our residents, we’re excited to see former researchers or folks who’ve worked in labs or run businesses or done other things that have ultimately contributed to the environments of our schools, but who may not have, in their traditional undergraduate education, chosen to study teaching,” Bates says of the program’s participants.

Drexel supports the city’s program in numerous ways through both its curriculum and intense mentorship and cohort engagement.

Residency teachers supplement their online coursework with face-to-face, on-campus meetings on the final Friday of each month throughout the academic term. The get-togethers allow residents to share best practices (or sometimes, commiseration) as they discuss their classroom experiences.

And starting this year, residents also have time off from teaching every Wednesday afternoon to meet with advisors, talk with instructors and work on their coursework.

“We’re curious to see how these Wednesday afternoons help them manage the coursework,” says Valerie Klein, assistant clinical professor and program director for Teacher Education programs in Drexel’s School of Education. “We want them to have a day where it wasn’t necessarily the case that they had to do it at night maybe after their kids went to bed and they just finished grading, like ‘Now I can look at my courses with the 2 percent of my brain power left.’”

With Philadelphia’s school district being large and diverse, residents are encouraged to visit other established teachers in their building to observe other teaching styles, and to visit other schools to see what classes are like in other neighborhoods.

This is why Jackson made visits to Penn Treaty School in Philadelphia’s Fishtown neighborhood and to the General Louis Wagner Middle School in West Oak Lane. The visits helped her see what her post-graduation teaching jobs might be like, she said, since Greenfield is relatively high performing and in a more affluent area than the typical district school.

“I witnessed two different teachers teaching to a class where no one was listening,” she recalls of one visit. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘I don’t want my classroom to be like this.’”

Even after the program ends and the students have graduated, their professional guidance continues. Drexel provides three years of post-program support to PTR students at no cost, including professional development, onsite coaching and networking opportunities. Graduates can also obtain additional certifications or a master’s degree still at a 50 percent tuition discount.

“We say once PTR, always PTR,” Ulrich says. “As teachers, we’re lifelong learners.”

Social Studies

It’s now late January at Greenfield Elementary, and Jackson and Charmont are prepping for class during a quiet period. This time, the roles of master and pupil are reversed; Charmont is looking over Jackson’s shoulder as Jackson prepares to take over the day’s lesson on decimals and fractions.

Charmont says it’s gratifying to see how far Jackson has come in her ability to command the classroom. “When she was first here, she was more of an amazing assistant,” Charmont notes. “Over time, she is taking control of the classroom, which is wonderful. She’s doing exactly what she should be doing. She’s managing transitions. She’s establishing routines for the students. She is developing strong lessons that engage the students with a variety of modalities… You’re experimenting with so many ways to engage them.”

Though the school year is only midway, Jackson already feels that she’ll be leaving in June with many new skills — like establishing effective reward systems, managing time and re-focusing student attention.

The program creates a natural feedback loop that aids the learning process, Jackson adds. Even when Jackson is leading a class, Charmont takes opportunities during the lesson to whisper suggestions into Jackson’s ear. Or, vice versa, Jackson will sneak over to Charmont’s desk to ask a question.

“I’m trying to get into a routine of taking notes and giving her direct feedback, now that we’re in this more stable situation where I don’t have to monitor every detail,” Charmont says.

Ideally, such intimacy comes naturally in an apprenticeship, but even when it doesn’t, the PTR program employs site directors, or University liaisons with education backgrounds, who visit classrooms weekly to provide additional help and feedback.

Pam Bryan, an adjunct with the School of Education who has been mentoring teachers for over 20 years, says her job as a site director is to promote positive communication between all parties, to help everyone grow.

“I provide communication support,” she says. “I’m a third person who’s not [always] around, so I can listen to both [the resident and mentor] objectively. They’re together all year long and may have different organizational, leadership and teaching preferences. So, how do you maneuver the differences?”

She recalls one pair she worked with who successfully navigated their differences and helped the students reach success by the end of the school year.

“They had many differences: world experiences, teaching styles, educational philosophies and working styles,” Bryan says of the resident and mentor. “What they shared was their desire for the students to experience academic success and that became their common working ground. From that point of reference, they built a practice classroom experience that focused on collaboration and exploring new ideas. It was a growth opportunity for all.”

Final Exam

By late May there are only a couple of weeks left in the school year at Greenfield. This prep period, Jackson is planning for class completely independently while Charmont works with students one-on-one.

Once class is underway, Jackson crouches down next to a student who seems hesitant to complete missing assignments.

“You’re an A student,” she encourages him. Then she tells him a story about how she moved recently, and she saved money little by little to ensure she could afford to do so — turning it into a lesson about planning ahead.

The scene captures the biggest lesson Jackson says she learned in her residency year that she will take with her into her own classroom.

“It’s important to be consistent, and to always hold the students accountable — holding them to very high expectations,” she says.

Jackson went on after her residency year to teach sixth- and seventh-grade math at Hill-Freedman World Academy in the East Mt. Airy section of Philadelphia starting in the fall of 2019.

Greenfield Principal Dan Lazar was sad to see her go.

“If we had had an opening to hire her, I think we probably would have because of how great she is,” he says. “She took every opportunity she was given to learn and to engage and to teach and just absorbed everything her mentor teacher was giving her. She really became part of the community here… It wasn’t a one-way street. We definitely benefitted from having her here as well.”

Testimonials like these showcase the power of the PTR program.

“If we can shorten that learning curve and retain people after the residency, I think we’re knocking it out of the park and demonstrating that the investment is worthwhile,” Bates says.