The wilderness photographer Ansel Adams once said that every experience is a form of exploration. Life is a call to action that takes you to a new place, and hopefully, to greater wisdom. Here at Drexel, we couldn’t agree more. We’re also fond of the old chestnut that experience is the best teacher. That’s what our educational model is all about, after all. And as we celebrate the centennial of the Drexel Co-op program, we honor not only academic experience, but also the interesting and rare life opportunities that come with a rich education.

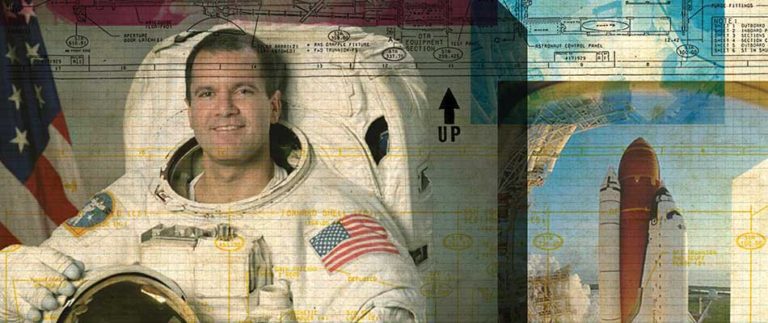

What is it like to do a spacewalk?

PAUL W. RICHARDS

BS Mechanical Engineering ’87

If you want to be an astronaut, you’ve got to be the best at something.

Of the more than 330 people selected by NASA to travel into space, nearly all are top pilots, scientists or engineers.

Paul W. Richards happened to be the best tool guy.

Richards, 55, is a mechanical engineer with degrees from Drexel (BS ’87) and the University of Maryland (MS ’91). After college, he worked on the Hubble telescope project as a designer of crew aids and tools for astronauts. Which means that when he applied to the astronaut program in 1996, he had already logged hundreds of hours with the devices in NASA’s underwater tank, simulating the slow, weightless ballet of an actual spacewalk.*

By the time he boarded the Discovery shuttle for his first and only spacewalk in March 2001, he had trained 17 hours for each hour that he spent outside the International Space Station, rehearsing routines forward and backward, using tools that in some cases he had personally designed.

So he felt totally chill, in other words.

“During the entire mission, I felt like I had been there before,” he says. “It seemed like my peripheral vision was fine-tuned; colors seemed brighter. We are trained so well it’s sometimes like the crew can read each other’s minds. It’s an amazing feeling to be that ready.”

Then you step out of the airlock into space, where the sun rises and sets every 45 minutes and temperatures swing 500 degrees in either direction.

“NASA trains the surprises out of you,” Richards says. “But they can’t train you for the view outside such as the sight of lightning strikes over Houston at 2 a.m., or the beauty of sunrises, sunsets, moonrises and moonsets. Around the Earth, you see the thin atmosphere lit up by the sun with spectacular colors. Parts of the ground look pristine and uninhabited; other parts seem very inhabited as you see smoke coming from power plants in China or sediment from a river reaching hundreds of miles into the ocean. Also, I didn’t train for the complete darkness on the backside of the space station, or for that moment, when your hand slips off the space station…and the heart races. Because you never want to fall off the space station.”

“They tell you all the odds about the danger of launch, but when it was me and I was going up, it was 50/50: I was either coming back or not. We all write two sets of letters for families back home: a MECO (main engine cut off) letter, and a good-bye letter. Once you start coasting in space, your MECO letter tells everyone back home how happy you are to be living your dream.”

For Richards, experiencing the immensity of space and the marvel of man’s ability to reach it left him more certain of the divine.

“To be traveling at 5 miles per second looking down at Earth from this machine that we built….for me, that opportunity to see the universe differently strengthened my faith in God. There is definitely a grand designer that we’re just beginning to figure out.” — Sonja Sherwood

* Remember Michael Bay’s space spectacular “Armageddon”? When Ben Affleck’s character is inside NASA’s underwater tank learning how to save the planet from an asteroid, one of the suited figures in the tank with him is actually Paul Richards.

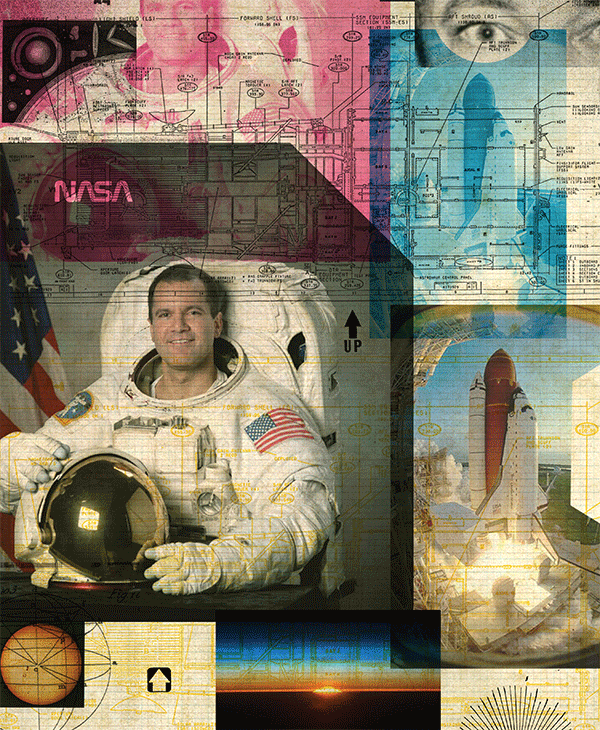

BASIL HARRIS’ “TRICORDER” WAS BUILT AT HIS HOME WITH FAMILY AND FRIENDS. ONE OF HIS KIDS CHANGED PRINTER HEADS; ANOTHER THREADED WIRES IN THE EVENING. AT THE END, THE FAMILY HEAVED A ‘HOORAY’ TO HAVE THE KITCHEN TABLE BACK.

What is it like to win an xprize?

BASIL HARRIS

BS architectural engineering ’92, BS civil engineering ’92, MS civil engineering ’94

It wasn’t until Basil Harris was at the Los Angeles awards ceremony in 2017 that he began to believe his team of seven siblings and friends could actually win the $2.6 million grand prize in the international Qualcomm Tricorder XPrize competition.

The victory was five years in the making, and it meant surviving 311 rival teams from 38 countries, including large teams with deep pockets. (Second place went to a powerhouse of 40 or 50 medical professionals and programmers backed by cellphone maker HTC and Taiwan.)

Harris, 49, was (and still is) a busy night-shift ER doctor and father of three working at Lankenau Medical Center and living in Paoli, Pennsylvania. But he grew up with an engineer dad (his father Harry Harris is a retired Drexel engineering professor) and a love for old “Star Trek” re-runs. He holds five degrees, including two undergraduate degrees and an MS in civil engineering from Drexel, a medical degree from Jefferson University, and a PhD from Cornell. He also has a number of patent applications to his name and a medtech startup he runs with one of his brothers called Basil Leaf Technologies.

So when the California-based XPrize Foundation — known for staging high-concept contests around innovations that solve major human challenges — asked teams to create a “tricorder” tool for rapid diagnoses like the fictional one Dr. Leonard McCoy used on the starship Enterprise, Harris cleared the table and began tinkering.

The objective was to create a handheld medical device that anyone could use at home to easily and instantly diagnose at least 13 health conditions and monitor five vital signs.

As a physician, Harris had an advantage over teams that were focused mainly on the tech. “I wanted to recreate what we do in the ER when I make a diagnosis,” he says. “When I approach patients I’m not thinking, ‘Hey, what cool tech can I put on this person?’ First, I need to know what information [about the patient] I need to gather.”

Joining the labor of love were four friends and three of Harris’ siblings: George, Gus (BS electrical engineering ’90) and Julia. They named themselves Final Frontier Medical Devices.

“When we started it was more kind of a fun project so that we could get together and have something to work on,” he says. “In the beginning, just being a part of building this iconic tricorder and advancing in the contest in any way was enough for us. I was a little in shock that we pulled it off. I wouldn’t have bet on us.”

They spent five years — just like the “Star Trek” series’ five-year mission, Harris jokes — bootstrapping a medical device they call the DxtER (pronounced “Dexter”). The team, spread out between Boston and Tennessee, got together nights and weekends to work on prototypes. Each of the 65 kits took 90 hours to print from scratch, and Harris’ house was filled with circuit boards and the hum of three 3D printers. “My kids don’t know life before tricorder building,” Harris reflects.

Like Harris himself, DxtER is an overachiever. DxtER uses sensors and artificial intelligence to diagnose 34 — not just 13 — conditions, including diabetes, sleep apnea, urinary tract infections and pneumonia. Once Harris has a working model ready, it could retail for $200 and diagnose more conditions, he hopes.

Today, he’s still working nights at Lankenau’s ER, fielding jokes from colleagues who tease him that he should be building tricorders full-time. A multimillion-dollar prize purse doesn’t go nearly as far as inner motivation, it turns out.

“Sometimes I think I should have taken the winnings and run off to Italy or Belize,” he jokes. “But no, we have been just doing more of the same… design, build, test and repeat. With the winnings we’ve been able to continue without investors. We are still operating in a startup mentality: no salaries or employees, just putting our heart and souls into building something we think is really cool and useful.”

DxtER units are going through calibration tests, and Harris hopes to launch a clinical trial that will include about 175 patients at the University of California in San Diego before the end of the year. Next: FDA approvals, and onward to commercialization and scaling up. At that point, Harris hopes to partner up with a big firm because the team will be boldly going where they’ve never been before… — Sonja Sherwood

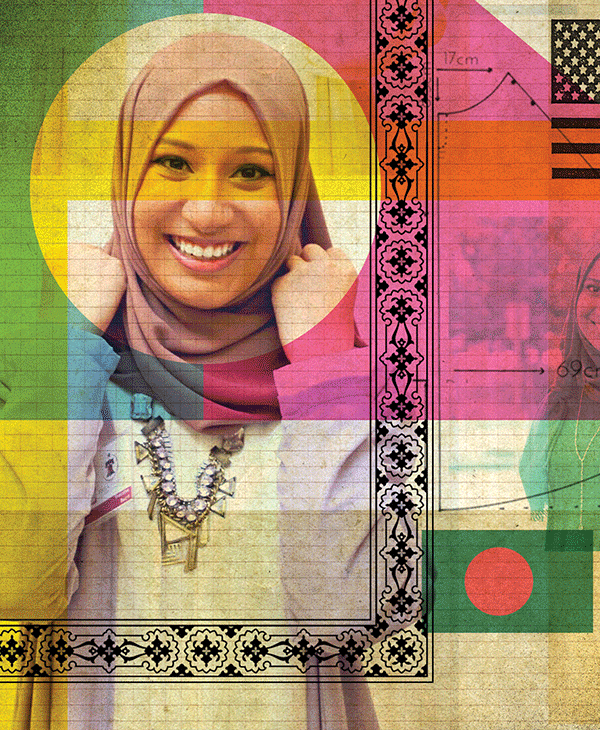

“I AM FREE TO PRACTICE THE RELIGION I PREFER,” SAYS NOOR JEMY, “BUT SOMEHOW WHEN I CHOOSE TO COVER MY HEAD AND MY BODY IN THIS BEAUTIFUL LAND OF FREEDOM, I AM SAID TO BE OPPRESSED.”

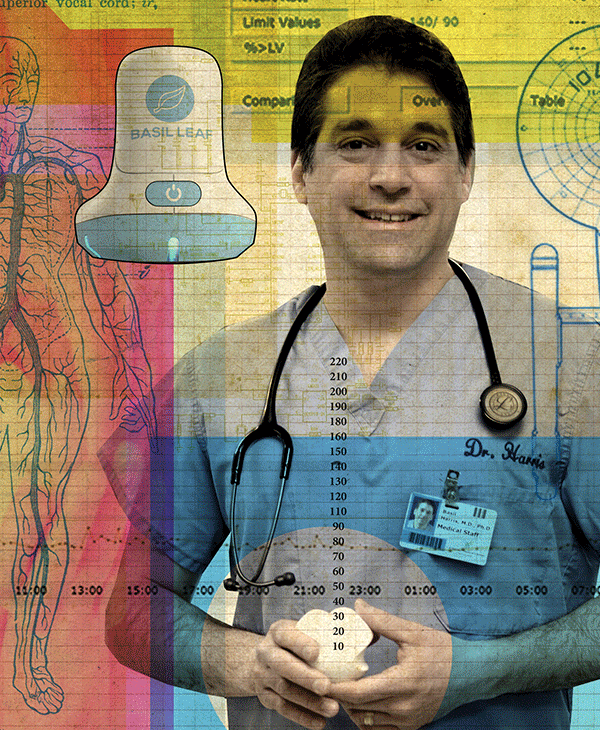

What is it like to wear a hijab in America?

NOOR JEMY

BS health services administration ’16

Islam has been a constant in Noor Jemy’s household for as long as she can remember. For almost as long, she has worn a hijab.

Jemy, 25, a 2016 health services administration graduate, emigrated with her parents to West Philadelphia from Bangladesh at the age of 3 and has lived on the cusp of University City ever since.

She says that throughout her life, her hijab has been a personal symbol of Islam and its principles that inspire her to be a good human being.

Wearing a hijab meant bedtime stories with her two brothers of the Prophet Muhammad and other prophets Moses, Jesus and Adam. It represented eating halal, speaking with respect, dressing modestly, and the prayer and knowledge conferred from reading the Quran with her parents.

She used to view her hijab as a symbol of her religion. Today, in an America rife with cultural tensions and political unrest, she says her hijab has become her shield.

“It’s a symbol of defiance — that I will not be swayed to tear away my identity,” says Jemy, who currently serves as the program manager for Graduate Student Services in the LeBow College of Business. “That 1,438 years of this beautiful religion being practiced, and with more than 1.7 billion followers, this religion of Islam cannot be painted with one stroke of an ugly brush.”

She notices whispers among strangers, stares charged with negativity, tugs on her headscarf from passersby.

Once, while waiting to catch a train at 30th Street Station, she heard a voice call out: “Go back to where you came from, you [expletive] terrorist.” She froze, her hands clutching her bag as her eyes burned. She was too shocked and saddened to respond.

“I remember everyone around me going about their way. Life continued on,” Jemy says. “The train arrived, and I boarded. And that was it.”

She says it’s “heartbreaking to be treated like an outsider in your own home,” to be viewed as an “other.”

“It’s a weird dichotomy because of how important freedom of religion is here in America,” Jemy says. “I am free to practice the religion I prefer, but somehow when I choose to cover my head and my body in this beautiful land of freedom, I am said to be oppressed.”

This perceived and sometimes projected oppression is the paradox of her hijab, Jemy says.

The more she read about women’s rights in Islam, the more she noticed her religion elevated women in a way that that gave them immense respect, honor and equity.

“We’re encouraged to go and seek knowledge and always pursue higher education and be independent, to vote, to make decisions in the house and in business and so much more,” she says. “The more I learned about women in Islam the more liberated I felt.”

She wishes more Americans saw and understood that liberation, too. But until then, her hijab will continue to remind her of her love for God, and her ability to rise above societal assumptions.

“I will keep saying it and showing it in any way I can here in America, my home,” Jemy says. “Through my words and actions, and ultimately, my hijab. Islam is peace. Islam is beauty. Islam is love. Islam is understanding. Islam is acceptance. It will always be all that and so much more.” — Maria Zankey

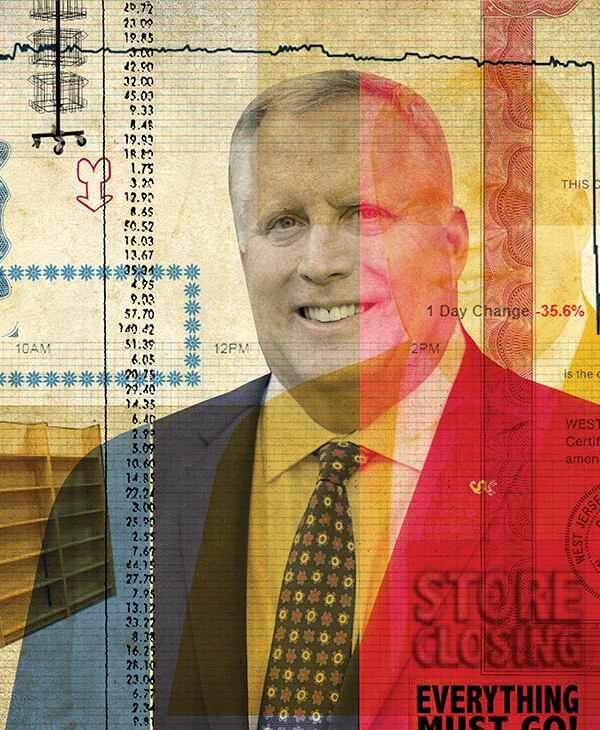

MIKE EDWARDS WAS CEO OF BORDERS WHEN DIGITAL BOOKS DROVE HIS COMPANY TO EXTINCTION. “YOU LEARN AS YOU GO, NO ONE TRAINS YOU TO BE A CEO,” HE SAYS. “ONE DAY, YOU’RE IN CHARGE, AND THAT’S A VERY BIZARRE EXPERIENCE.”

What is it like to lose a business?

MIKE EDWARDS

BS business administration ’83

According to legend, it took the members of The Buggles just one hour to write the popular tune “Video Killed the Radio Star” inside a London apartment in 1978.

In 2010, it took Mike Edwards, BSBA ’83, just one week to realize that the book and music mega-retailer Borders Inc., of which he was CEO, was similarly doomed by changing tastes and technology.

“The first week the Apple iPad came out, we dropped 6 percent in sales because people just downloaded books,” Edwards recalls. “The company was already wounded because music became digitized, video became digitized and now books — the biggest category — was shrinking.”

The $2.8 billion, 715-store retailer filed for bankruptcy just a year later. Edwards normally prides himself on his abilities to be innovative, pivot fast and see around corners, but he admits he didn’t see it coming. When he became CEO in 2009, Borders wasn’t doing well, but he thought it could be turned around.

When his intuition proved wrong, he viewed it as a learning experience. “With Borders, at a certain point, you couldn’t save the patient,” he says. “All the best intentions in the world, but when the banks pull the plug and you have no capital and you can’t pay the bills, that’s the hard lesson of business not performing.”

There were a few glimmers of hope before Edwards resigned himself to liquidating the company in July 2011. First there was a rumor — false — that Barnes & Noble might acquire Borders. Optimism rose when Edwards lined up an investor for a bridge loan to keep things afloat. But the investor pulled out the day before the deal was to close.

“We went from thinking we would come out and survive, to filing a Chapter 7,” Edwards recalls.

Edwards likens the five months between bankruptcy and liquidation to running a marathon. He cut underperforming stores, renegotiated leases, closed distribution centers, eliminated third-party vendors and reduced corporate overhead — all while running the business and trying new sales tactics.

“It’s sort of being realistic with your team about the risks but also waking up every day with a sense of optimism and pushing as hard as you can to accomplish the goal,” Edwards says of his feelings at the time. “Mentally and emotionally, it’s fatiguing.”

In the end, the book superstore went the way of the radio star. Immediately after filing the petition to liquidate, Edwards and his CFO flew back to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to deliver the bad news to the remaining 600 employees at Borders’ corporate office. Instead of the reaction one might expect, they were met with a standing ovation for their efforts to save the company.

“We came close, but it wasn’t meant to be,” he says. “But, you know, a good failure is just as important as a lot of wins in one’s career.”

His experience with Borders will not be Edward’s only legacy. The 59-year-old went on become president and CEO of online luggage retailer eBags from 2015–2017, and in April became president and CEO of Portland, Oregon-based children’s apparel corporation Hanna Andersson.

As a Drexel trustee, he sometimes counsels business students to keep a sharp eye on industry changes.

“AirBnB was considered a very bad idea for a long time, but they disrupted the hotel industry and Uber disrupted the taxi industry and Apple disrupted the music industry and Amazon disrupted all the industries,” he says. “The fact of the matter is the industry around you is changing. When you see a bad trend, sometimes you can’t fix it.” — Beth Ann Downey

What is it like to be a sniper?

DANIEL NAVIN

BS mechanical engineering ’17

Fully half of all the soldiers who try out for sniper school — yes, sniper school is an actual thing — fail out. The demands for peak fitness and sharp mental attention mean very few people are even nominated. Those who graduate get a coveted assignment: high-powered rifles, magnified optical equipment and the chance to sneak through enemy territory in small teams. The job has a heroic, elite quality. The stealthy, skilled sharpshooter saves soldiers’ lives. That is the hope.

Daniel Navin, 35, joined the Pennsylvania Army National Guard straight out of high school in 2003 and went to sniper school in 2008. He was a natural choice for the sniper program: physically fit and fluent with firearms already from a childhood spent shooting BB guns and rifles in his backyard as a self-described “country boy.” Navin finished the two-month training program handily and in 2009 he deployed to Iraq with the 56th Stryker Brigade combat team.

He arrived in an area north of Baghdad nicknamed the Triangle of Death. The area is densely populated and riddled with insurgents and roadside bombs. His job during the 10-month deployment was to spot things that looked out of place, to protect the team, to neutralize the enemy.

“You have to be able to rationalize what you’re doing and how it fits into the big picture of saving American lives,” says Navin. “You’re given a high-powered rifle and your country is asking you to kill people and you have to have the maturity to cope with that.”

His first week in Iraq, a team went out without a sniper, and a soldier was shot in the head.

“After that, we were always with the guys ready to respond and it put a lot of pressure on us,” says Navin. They did foot patrols at night, kicked in doors at 3 a.m. to round up suspects, and walked into dozens of potential booby-traps.

All of which could be exhilarating, when you’re 24 and this is what you trained for, Navin says. “You’ve trained with a bunch of guys and you’re excited to be there — it’s almost like being a pro athlete because you’re ready and you’re finally in the game.”

But living with constant danger also plays with your mind, Navin says. “Looking back on it now, I can’t believe we did what we did and are still around today,” he says.

A touch of paranoia is a life-saving mentality for an infantry soldier in a combat zone, and it has since helped Navin as a civilian. While completing his degree in mechanical engineering at Drexel, he and fellow veteran James Ostman (BS mechanical engineering ’17) invented a device called the Ballistic Curtain Cordon System to protect people in public venues from mass shooters. It’s a bulletproof curtain that drops from a ceiling in a matter of seconds to provide cover for bystanders as they flee gunfire.

As public spaces increasingly come to resemble combat zones, Navin moonlights on development of the curtain while working with his wife at a family business in Pennsylvania in hopes that his startup will one day succeed in shielding citizens from danger. — Sonja Sherwood

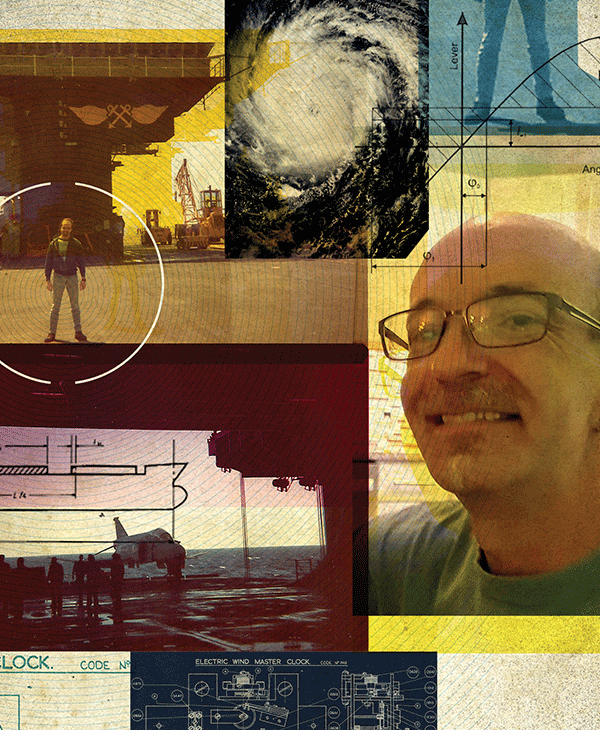

What is it like to ride out a typhoon at sea?

ALAN ROHANNA

BS mechanical engineering ’90

Large U.S. Navy ships are built to survive storms, but they aren’t invincible.

The most famous case of Navy vessels foundering at sea is the story of Task Force 38, a fleet that was surprised by Typhoon Cobra in the Philippine Sea in 1944. Hurricane-force winds tossed the ships on massive waves and sank 46 aircraft and three destroyers, drowning 790 men in the roiling waves.

The enormous losses inspired the Navy to establish a typhoon tracking center on Guam, among other improvements. No large naval ships have sunk in storms in the past 70 years.

Maybe that’s why Alan Rohanna was able to laugh his way through eight to 10 hours of oceanic churn and winds that reached 120 mph.

Rohanna was one of more than a dozen federal employees with the U.S. Department of the Navy who rode out a super typhoon on the Pacific Ocean aboard a U.S. Navy destroyer. At the peak of the storm, a homemade chronometer — a device that measures the list of the ship — indicated the ship was tilting up to 26 degrees from one side to the other.

Rohanna, who is 52 now but was 27 at the time, and his shipmates decided to have fun with it. They took an enlarged photo of their boss’s face and attached it to the weight of the chronometer.

“Because his last name was Wos, we called it a Wos-o-meter,” he says, laughing at the memory. “That’s what you have to try to do to keep your mind off things and, you know, hopefully make it out alive.”

Rohanna started working for the Navy at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard — now The Navy Yard — during his first co-op in 1987 and continued there for two subsequent co-ops, graduating with a full-time offer. He worked there through the closure that turned the shipyard into the mixed-use development it is today, and was then transferred to a post in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1996, where he’s worked for the past 22 years.

In 1994, he and his colleagues were flown from Philadelphia to Pearl Harbor, then boarded a Spruance-class destroyer set for a nine-day-long voyage across the Pacific to Yokosuka, Japan, on a work mission to study discrepancies in the propulsion and auxiliary systems. The trip took them right into the path of Super Typhoon Zelda.

“The captain was trying to veer away from it, obviously, because you don’t want to go through the center of a storm,” Rohanna says. “Even with him doing that, the seas were obviously quite rough.”

After docking safely, Rohanna never fully recovered his sea legs. “Once I stepped foot on the pier I was like, ‘Oh my God, I’m not doing this ever again!’” he says, and nearly 25 years later, he hasn’t.

“I have zero interest in going on a leisure cruise to Holland or wherever else, even though it’s a totally different situation,” he says, still chuckling. “I like the solid land.” — Beth Ann Downey

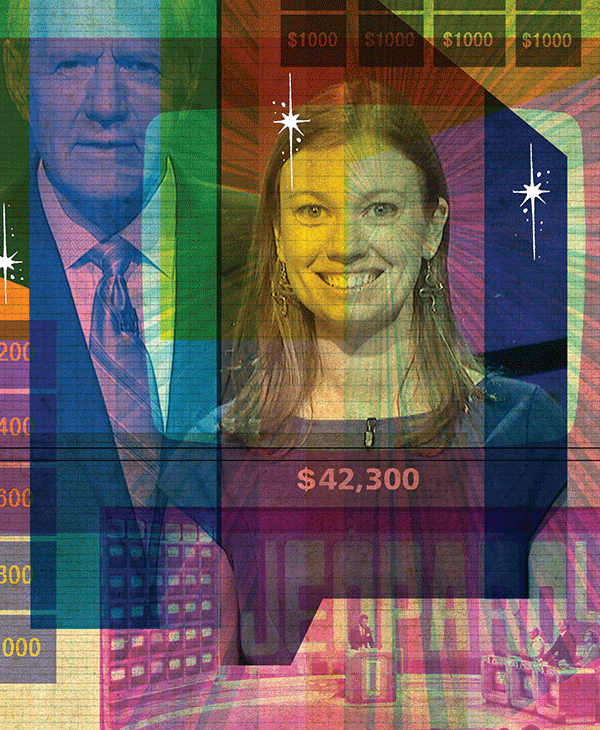

BEING ABLE TO JOIN A SECRET FACEBOOK GROUP OF PAST WINNERS IS ONE OF THE PERKS OF BEING CHOSEN TO COMPETE ON THE QUIZ SHOW “JEOPARDY!,” SAYS JESSICA JOHNSTON

What is it like to be on ‘Jeopardy!’?

JESSICA JOHNSTON

MS higher education ’15

Getting on “Jeopardy!” isn’t easy. More than 70,000 people take the quiz show’s online qualifier test, 3,000 are invited to audition, and about 400 are actually chosen — which Jessica Johnston figures is less than half a percent.

Johnston, 33, appeared on several episodes in March 2017, and the Scripps College admissions recruiter won a respectable $42,300 as a two-day champion.

Fewer than a quarter of contestants win multiple episodes.

“I only tried this on a whim, so I was surprised to get as far as I did,” says Johnston, a quizzo buff who took the online test at the suggestion of her boss. “I just sort of went into it with the attitude that, ‘Well, this will always be a good story.’”

To qualify, she needed to answer 35 or more out of 50 “Jeopardy!” test questions, each timed at eight-second intervals. Finalists then attend an in-person audition, and a chosen few are invited to a taping in Los Angeles, where producers record five episodes in a single day.

Beforehand, contestants have to write answers to more than 30 ice-breaker questions about themselves, so that Alex Trebek can make casual chit chat with them on screen. (“And he went totally rogue and asked me something not on the card at all!” Johnston complained.) Johnston also vividly recalls the producers’ pep talk advice in the ‘green room’ before taping: don’t look weird, don’t fall off the platform, don’t be that person.

Johnston says she worried more over what to wear on screen than about studying up or mastering a wagering strategy.

“So much of it is luck of the draw and just the categories you get,” says Johnston. “There were some categories that came up where I was like, ‘Oh man, are you kidding me?’ There was one about fungus, another one about RVs, and I thought, ‘This not going to be my day.’”

The question that doomed her winning streak was about t

he Gotye song, “Somebody That I Used to Know.” She forgot the word, “That.” Another contestant got it right, and he ended up beating her that day by $200.

“I still can’t listen to that song,” she says. But no matter. She won a nice chunk of money for her favorite thing: travel. She immediately booked a cruise to Antarctica.

The best, most surprising thing about being on the show? How nice everyone is. You join a big, but still pretty exclusive, club of tens of thousands of smart, friendly contestants, and Johnston says she made new friends and there’s even a secret Facebook group.

“You think you’re all going to be sitting in the ‘green room’ glaring at each other, but …. there’s really much more of a community than I ever expected,” she says.

— Sonja Sherwood

DR. SANDRA LEE’S REALITY TV SHOW “DR. PIMPLE POPPER” IS NOW IN ITS THIRD SEASON AND HER YOUTUBE CHANNEL HAS MORE THAN 3 BILLION VIEWS.

What is it like to be a reality TV Star?

SANDRA SIEWPIN LEE

MD ’98

Dr. Sandra Lee, 48, is not, herself, a “pop-aholic.”

That’s what she calls the cohort of social media users who enjoy watching dermatological “popping” videos online — a much larger cohort than she realized existed when she started posting these types of videos four years ago. For her, it’s a profession; but for the fan base she’s tapped into and which has propelled her to reality TV fame, popping is a passion.

Lee, MD ’98, graduated from Hahnemann Medical College, which is now the Drexel College of Medicine, and is known as “Dr. Pimple Popper” for her role on the TLC reality show of the same name. Now in its third season, the show is the most-watched cable TV show on Thursday nights. Lee also boasts 3.4 million followers on Instagram and has racked up more than 3 billion views on her YouTube channel.

“Yes, that’s with a ‘B,’ that’s crazy,” remarks Lee, who lives in Upland, California, with her husband and fellow alumnus Jeffrey Rebish, MD ’98. “I just thought people would like to see a window into my world.”

Although her father was also a dermatologist, Lee says she didn’t get interested in the specialty until medical school. After completing their professional qualifications, Lee and Rebish settled in California, where Lee is from, and took over her father’s practice upon his retirement. Skin Physicians & Surgeons is now a familiar setting for Dr. Pimple Popper viewers, but back when Lee was about a decade into her career, the popping videos she began posting online were just starting to gain traction.

“Early on, I think I had posted a blackhead extraction video and it got a noticeable increase in attention. I didn’t know what to make of that; I thought it was really strange. So, I did it again and it happened again,” she recalls. “Then a few months later, Buzzfeed posted a reaction video to my video on YouTube … and I think I gained like 20,000 followers in a few hours.”

A few years after Lee went viral, a production company came knocking. They wanted to create a reality TV show around her and her practice.

Lee was hesitant. “I really wasn’t interested in it completely because it’s sort of like me handing over control to somebody else, and I didn’t really like that idea because reality shows are scary,” she says. “I was concerned with how I would be represented, how I would be portrayed and how my patients would be portrayed.”

But once she said yes and the July 2018 pilot episode did well, she saw that the show could provide something positive for fans.

“I think it’s a really feel-good thing,” she says. “In this day and age we have so much negative stuff, and reality shows with people tossing tables or getting into fights, but it’s the opposite here. We might have something that is shocking or something that people haven’t seen, or that might seem gross to people, but we’re actually making it normal, and going the opposite way.”

Being a reality TV star was never Lee’s dream. In fact, being famous was pretty hard for her to get used to. But she sees this attention as a platform for the mission she holds dear to her heart: bringing dermatological knowledge and high-grade skincare products to people who might not have access to them. She’s doing this by continuing her YouTube channel, through her SLMD Skincare line, and with her book, “Put Your Best Face Forward,” which was released in December.

With her status, Lee also takes very seriously her opportunity to serve as a role model, especially for her younger fans.

“There are so many 5-year-olds, 8-year-olds, 12-year-olds who are obsessed with Dr. Pimple Popper,” she says. “I get so many photos the first day of school when they say, ‘When I grow up I want to be’ and they put in ‘Dr. Pimple Popper,’ or they dress up like me on Halloween.” Future “pop-aholics” in the making. — Beth Ann Downey