Brian Sullivan ’17 was 33 days into production on his first feature film, working long past midnight on an exhausting day of shooting, when he finally broke into the heart of it.

He had been filming the firefighters at the center of his documentary for months and had known some of them much longer, but even halfway through the shoot he still wasn’t sure what would come of it. That night, with his usual crew finished for the night — no sound guy, no producer, no second camera to back him up — he sat with members of the fire house for an emotional interview that brought the truth of firefighting and filmmaking into sharp focus.

When he dragged himself home at dawn, Sullivan, who graduated from Drexel this spring with a bachelor’s in film and video, blearily dashed off an email to Thomas Quinn, director of the film & Video program in the Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, who had first convinced Sullivan to turn a short film he threw together from odds and ends of footage into a full-length feature.

“Breaking that barrier with cast members into their deepest, darkest personal secrets, and hearing the nightmares they’ve had every night for four years, is something I never in a million years expected to get on camera,” Sullivan wrote to Quinn. “Listening to these people relive the most harrowing and humanizing things they’ve ever been a part of, detail by detail, hour by hour, is something I didn’t really ever think I’d get as a filmmaker.”

That intimacy, gained by developing trust over months and years, is a rare quality for a student film, and full-length student films are rare in their own right. Sullivan’s movie, “Behind the Bay Doors,” which is winding its way through the post-production process with eyes on a 2018 release, is just the program’s third, Quinn says. It explores the lives of the people who run into a fire when everyone else runs out — the people who protect their communities whether or not they’re recognized for it.

Fifteen of the 17 film crew members are Dragons, several of whom graduated in the spring alongside Sullivan. They handled the sound, the editing, the production and the photography. They spent the better part of two years following Sullivan’s lead to get to this point, even when it took them into burning buildings.

Sullivan will never forget his first fire.

September 2013. A two-story twin on Fairview Avenue in Abington was fully engulfed, plumes of black smoke stretching skyward, billowing above the surrounding trees. The call came in shortly before midnight and brought together nearly 100 firefighters from neighboring departments to battle the flames in an orange haze. Sullivan stayed on the fringes, a bystander with camera in hand, documenting the scene into the early hours of the morning. It was the first time he truly understood a fire’s power.

“I was about a block and a half away,” Sullivan says, “and I felt like I was in an oven.”

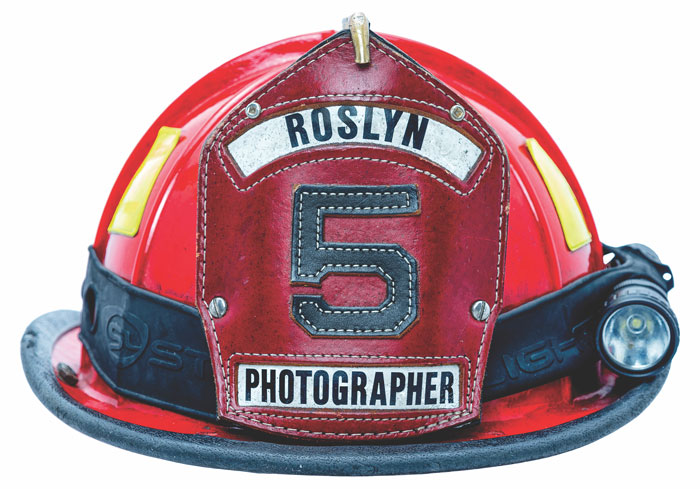

The chief of his local fire house, Dale Jonas of the Roslyn fire Company, was so impressed by the pictures Sullivan posted on social media after that night on Fairview that he wanted to learn more about the kid who’d taken them. Come on down to the station, he offered, and let’s talk about what you can do in the future. Jonas gave Sullivan a pair of keys and told him to come around anytime. He’s been coming around ever since.

He began toying around in a sort of journalistic capacity, filming and taking pictures most of the time. Before long he had enough footage to make a short film, inspired by a class with adjunct professor Steve Acito, that gave viewers a glimpse of life in a fire house.

“They brought me under their wing and I was able to go behind the bay doors, so to speak, and see what it’s like on the inside,” Sullivan says.

The short, shot through with dramatic cinematography, immediately attracted attention, drawing more than 40,000 viewers in its first week on Vimeo as it got passed among the firefighter community. But Sullivan knew offering a glimpse wasn’t enough. The audience had scarcely enough time to learn the names of the firefighters he interviewed, let alone connect with them enough to be moved in any way.

“Everybody wanted to know more,” Sullivan says. “You can’t explain a way of life in nine minutes.”

Quinn had the same reaction. Every time a firefighter started saying something interesting, they were cut off. He knew there was more story to tell. So he took an unusual step and suggested Sullivan think about making a long-form piece.

They brought me under their wing and I was able to go behind the bay doors, so to speak, and see what it’s like on the inside.

At first, Sullivan laughed it off. Students just don’t make feature-length films, he thought. But two months later he was in Los Angeles for the “Westphal in L.A.” summer program, living with four friends he’d had since his first term at Drexel, a group that had already formed a tight-knit production crew on various projects, and he decided there was nothing holding him back. They settled on a target budget of $25,000, devised a plan for raising the funds — part crowdfunding, part private investment and part work-for-hire with fire companies in need of promotional videos — and started rounding up the people who could make it happen.

Sergio Galeano joined the team to do sound when he was still just a sophomore in the spring of 2016, shortly before the crew started filming.

“Brian showed me the short and I was blown away,” Galeano says. “It was clear there was an idea here, clear that this had a trajectory. And not all college productions do.”

The idea, as Sullivan saw it, was to show people what it’s actually like to step into a fire house and suit up. Fighting fires is part of it, sure, but so are the more routine aspects of the job — running drills, cleaning the space, sharing meals. He wanted to dig into the personal motivations each individual holds dear, and the way those individuals coalesce, over time, into a family.

“Firefighting isn’t necessarily what people expect,” Rachel Tinkelman, the film’s story editor, says. “Brian didn’t want the Hollywood blockbuster version of firefighting.”

The crew didn’t have much of a choice, anyway. As Tinkelman says, “You show up to a fire company on a scheduled day, but you can’t schedule a fire.”

Chris Manning, at 41, is a 21-year veteran of the Flourtown fire Company, one of the houses profiled in the movie. He knows as well as anyone that the moments that speak the loudest about life in a fire house are often the quietest, when a blaze is nowhere to be found.

“If somebody’s going to watch this as a documentary about hardcore firefighting, it’s just not for them,” he says. “It really is about the small fire department, about the camaraderie, the sacrifices that are made — all these things that go on behind the scenes.”

Sullivan and his team understood that from the very beginning, Manning says, and it won them the respect of their subjects. They were careful in their approach, sensitive to the stories of the people they filmed.

“It felt natural to have them there,” Manning says. “We knew they were there to capture something that is important and that we think people should know about.”

By the time a feature-length version of “Behind the Bay Doors” began coming into focus, Sullivan had been hanging around fire houses for at least two years. He knew he couldn’t just throw a bunch of unprepared film students into the fray. The crew was in for some training.

For three months, Sullivan did everything he could to get his team trained in operational awareness and the tactical side of firefighting. He gave them hours-long slideshow presentations to learn the vernacular. If they wanted to be there for the big moments, they needed to know their way around a truck and what to expect when a call came in.

“These guys know what they’re doing,” Galeano says of the film’s subjects. “They’re in that truck before we can even blink and they know the protocol off the top of their heads. So the challenge was mostly keeping up with them, and also keeping up with our gear.”

The equipment — both firefighter and film — presented its own complications. It’s hard enough getting a boom microphone into position or maneuvering a camera around tight quarters, but tack on a pair of bulky, heat-resistant structural gloves and the degree of difficulty ratchets up. No film school can prepare a camera operator for that.

But gloves were just the beginning of the gear the crew needed to follow the firefighters out on a call. In order to get on the truck, they had to suit up in boots, suspendered bunker pants, a fire-retardant hood, a heavy turnout coat, a 40-pound self-contained breathing apparatus and a helmet, all in less than 30 seconds. Once the helmet goes on, it feels like a watermelon bobbing above your shoulders, Sullivan says.

To train his crew members, Sullivan took them to live burns — controlled building fires used by firefighters to train for the real thing. Sean MacIntosh, the film’s director of photography, recalls the experience vividly.

“It was hot, obviously, and tough to breathe, because you’re wearing the face mask for the air and everything,” MacIntosh says. “It’s a very different experience. Claustrophobic. You feel very enclosed. Your adrenaline’s pumping and you’re sucking in air. It’s exciting and scary.”

Finally, by March 2016, they were ready to start shooting. Sullivan and his crew had arrangements to visit two fire houses over 70 days of principal photography and their budget had risen to $80,000, a gap they filled by taking on more work for fire companies. Over the course of production, the crew was on hand for 48 calls, 15 of which were considered major incidents — fires, rescues and the like.

The crew applied their training when emergencies arose, but still faced the unique challenges offered by the subject matter.

“When we film, we think about not dying, not getting ourselves caught in a sticky situation and getting the shot,” Sullivan says. “We’re not worried about the technical stuff. Everybody asks what lens we used. I don’t care. As long as we’re not in a dangerous situation, the lens is secondary.”

The crew came away with 90 hours of material that are being condensed by lead editor Sean Higgins, a TV and media management sophomore, into a 90-minute film. It will hew largely to Tinkelman’s story outline, following six firefighters at varying stages of their careers. The younger volunteers had their illusions about life in a fire house dispelled along the way, and the film’s audience will share those journeys, Tinkelman says.

Two years ago, when all that existed was an intriguing short film and an ambitious 20-year-old director, getting to this point might have seemed like a shot in the dark: a group of raw college students tackling an unpredictable subject, learning on the fly about the realities of documentary filmmaking. With the right training, though, it all came together.

“It was daunting for the fact that we’d never done it before, but we wanted to so bad,” Galeano says. “It just seemed to make sense to do this. There was no reason why we shouldn’t, other than fear, and forget that, we’re almost firefighters. They don’t see fear, so why should we?”

Late last spring, Sullivan stood on the front apron of a fire station in the midst of a night of filming, feeling unusually relaxed. He put the camera down and watched the sun set, taking in the moment with a level of calm he rarely felt throughout the film’s production. It gave him a chance to reflect on what it took to get to this point.

“I’m going to miss that — the friendships that I’ve made,” Sullivan says. “These guys will be able to look back in 30 or 40 years when they have kids and watch themselves going through something that’s really integral to their lives.”

Sullivan was referring to the documentary’s subjects, but he could just as well have been talking about the young men and women behind the camera.

He went into the project expecting some good moments, a decent bit of action. He didn’t anticipate the depth he would encounter in feature-length filmmaking, the intimate, behind-closed-doors conversations he would have with his subjects. On that revelatory night midway through the shoot, his subjects opened up about some of the most traumatic moments of their firefighting careers, sharing memories that would otherwise remain bottled up inside of them, weighing heavily.

Suddenly, Sullivan was seeing the inner lives of the men and women on the other side of the camera. As he told Quinn in that early-morning email, he learned that if he pushed hard enough, he would end up in the right place, at the right time, with the right people to catch something special.

“So many hours of footage I couldn’t have dreamt up in a million years happened tonight,” Sullivan wrote to Quinn. “It’s part of the thrill of being a documentary filmmaker. You never know what you’re going to get when you start filming for the day.”