Illustration by Aleksandr Savio

Early in the 1980s, universities across the United States faced declining numbers of college-aged students, and an upstart California computer company was scheming to topple its titanic rival.

These unrelated circumstances intertwined when Drexel and Apple Computer Inc. inked a deal that allowed students and faculty to buy newly minted Macintosh personal computers at a deep discount in March 1984, before the general public could acquire them at any price.

The historic partnership propelled Drexel into the national spotlight and gave Apple — then just an eight-year-old startup — a template for success in the lucrative higher education marketplace.

The partnership stemmed from Drexel’s decision to answer demographic and technological trends with a bold move mandating computer experience for all students. That policy — announced in 1982 by Drexel’s then-president, William W. Hagerty — set in motion a series of changes to campus and to learning and teaching modes to help students succeed in the emerging digital era.

The story of Drexel’s Microcomputing Program, as the initiative was known, illustrates how University leaders anticipated the workplace of the future, just as A.J. Drexel vowed the institution would do when he founded it in 1891.

Head of the Parade

By the early 1980s, Drexel had already acquired three decades of experience with computers, mostly for academic research and administrative data.

The 1984 Drexel Macintosh 128K — complete with a blue “D” for Drexel — that was distributed to Drexel University students in 1984.

Drexel opened the first computing center in Delaware Valley in 1958, making it one of just 75 educational institutions in the country to offer one. The center provided training, supported research and helped faculty teach classes related to programming and digital computers for engineering, mathematics and business.

Computers quickly gained a broader presence at Drexel. A computer science-mathematics major was first offered in 1975, and the library began incorporating computer services and searches.

In 1980, Bernie Sagik arrived as vice president for academic affairs, as massive changes swirled on and off campus. Drexel had transitioned from an institute to a university just 10 years before, economic and demographic trends hampered enrollment, federal financial aid sustained deep cuts and the local population was declining.

Sagik proposed mandatory computers only for engineering students. Hagerty initially rejected the idea but changed his mind when business colleagues told him to open it up to all students and bask in the national publicity that would inevitably come.

Once Hagerty approved the idea for the Microcomputing Program, he set an ambitious pace.

“The freshmen now entering Drexel will spend the greater portion of their professional lives in the 21st century, in an environment in which the computer will be an everyday, even commonplace tool,” Hagerty proclaimed. “In every field of endeavor the successful practitioner will utilize computer technology in order to understand and deal with the challenges of everyday life.”

Hagerty’s announcement meant that all incoming students starting in 1983 would need access to a personal microcomputer — a first within higher education that earned Drexel a national reputation as a bold and technologically advanced institution.

But the aggressive timeline worried Sagik and the faculty, who urged Hagerty to delay the start date until 1984.

“Fundamentally, what he said was ‘By 1984, everybody else will have done it and you’ll be bringing up the end of the parade, and that’s not where Drexel wants to be,’” Sagik recalls in “Going National,” a documentary about Drexel’s deal with Apple.

There was much work to do. Internal reports showed that on-campus computer literacy was poor at the time. More than half of the full-time faculty members had used computers, but only one in five had taught with them. Most who had prior experience were scientists and engineers who used machines for computations and research.

An Academic Community Rallies

Brian Hawkins, then the assistant vice president for academic affairs, was tapped to oversee the integration of technology throughout Drexel’s campus, community and curriculum.

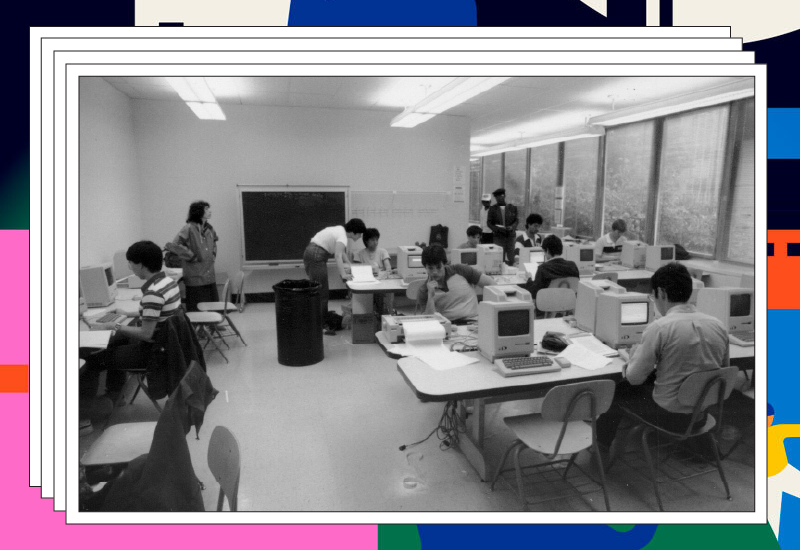

Drexel spent about $7 million (about $22 million in today’s dollars) updating its campus technology infrastructure. The University created “clusters” outfitted with shared computers and printers and staffed with co-op students, while academic departments got their own machines.

With a $2.8 million grant (almost $9 million today), Drexel started computer training classes and seminars that about 70% of the faculty attended in 1983. Additional faculty completed introductory seminars on word processing, spreadsheets, database management and educational software.

“I had pre-existing programming experience, but I didn’t know how to use a spreadsheet or a personal computer,” recalls Eva Thury, associate professor of English in the College of Arts and Sciences.

Thury had started at Drexel in 1979 as a graduate student at the School of Library and Information Science (today’s College of Computing & Informatics) and as an instructor in the English Department. Later, she began teaching computer programming classes for English students.

Using an Apple Lisa (a business computer that preceded the Macintosh), Thury wrote Tools for Writers, a program that allowed students to analyze and revise their work or to improve their skills. Later, she shared the project with M. Carl Drott, then a School of Library and Information Science associate professor (and her future husband). The program tallied words, sentences and other stylistic characteristics. Thury also developed “literature labs” where students used the software to talk about style in quantitative ways. Tools for Writers was eventually used throughout Drexel and sold nationally through Apple’s program catalog.

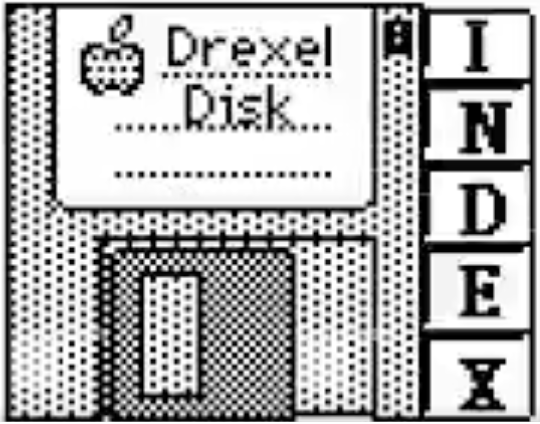

A computer savvy community of collaborators coalesced. Thury and other Drexel faculty developed nearly 100 programs — sometimes with help from students or expert programmers — to use in courses, ranging from an electronic periodic table to a program that could replace polygraph machines. Dragons also developed University-specific programs, like the Drexel Disk introductory software given to all entering first years.

Professors had become computer proficient in time for the 1983–84 deadline. But choosing which computer to adopt would pose unprecedented challenges.

Picking the Apple

Drexel’s computer mandate did not specify a brand, but a deal with a manufacturer could make computers more affordable for students and allow for uniform deployment across campus. The national attention Drexel garnered from its policy gave campus leaders hundreds of options.

The computer had to be sophisticated enough for technical users and programs but flexible enough for novices. A portable, stand-alone unit would serve the needs of commuters who made up half the first-year class and enable students to use their computers on co-op.

The University had equipped its computer centers with IBM machines for decades, giving the company a significant advantage. But IBM balked at Drexel’s $1,000 per-unit price cap (about $3,000 today), for which the University had issued a bond to make a high-volume purchase of computers to resell to students.

IBM’s much younger competitor, Apple, was content to meet Drexel’s demand, provided the University agreed to secret negotiations that kept details of its newest, unreleased personal computer under wraps.

It fell to Bruce Eisenstein, Arthur J. Rowland Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, who headed the College of Engineering Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, to vet Apple’s offerings. The company promised a machine with novel properties: a mouse, a screen with icons and font options. It was more powerful and far easier for novices to master than earlier personal computers, since no one had to memorize or enter coded commands. And Apple agreed to a $1,000 price tag for a model that would retail for $2,495.

I said, ‘Listen, you have to forget the IBM. This new computer from Apple is the one you have to get.’

“I went back to the selection committee, and I said, ‘Listen, you have to forget the IBM. This new computer from Apple is the one you have to get. They are going to make it available to us for a thousand dollars — that’s all inclusive.’ And the first question was ‘Is it compatible with the IBM computer?’ Well, no. ‘Was there software for it?’ No. ‘Were there any programs for it, like a word processor?’ Not yet. So, the committee justifiably kept saying, ‘Well, what’s the name of this? What’s it like?’ I couldn’t tell them. I had to say ‘You just gotta trust me on this.’ So they took a vote and unanimously voted to adopt the unknown computer that turned out to be the Macintosh,” Eisenstein recounts in “Building Drexel: The University and Its City, 1891–2016.”

Drexel chose the untested Macintosh, knowing that Apple wouldn’t publicly unveil it until January 1984 and that the computers wouldn’t be ready until March, almost halfway through that momentous academic year.

The University’s agreement laid the groundwork for the Apple University Consortium, made up of 23 more institutions including Ivy League schools that followed in Drexel’s footsteps by committing to plan and implement personal-computer applications with the California startup.

Countdown to 1984

In the fall of 1983, Drexel welcomed its largest first-year class ever, with 1,882 students. The class included 500 electrical engineering students, up from 120 or 130 in previous years. Only about 20% of male first-years and 9% of female first-years owned a programmable computer.

Those students still didn’t know what computers they’d already purchased, or when they’d get them. The mystery evaporated after an arresting Ridley Scott–directed commercial that aired during Super Bowl XVIII proclaimed: “On January 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’” Two days later, Apple introduced the Macintosh in a press release that also announced the Apple University Consortium.

By the time 2,000 Apple computers arrived at Drexel, campus officials had put elaborate plans in place to store and distribute the machines. Staff verified the contents of each box and added to the bundle. Each Macintosh 128K package included a computer, mouse, keyboard, power cord, manual, system diskette, blank disk for backup, programming switch, audio cassette “guided tour,” user manuals and programs including MacWrite, MacPaint and Microsoft Multiplan software. Each computer was branded with a blue Drexel “D” (known as the “flying D”).

Students picked up their machines starting on March 5, with 60 time slots per hour spread across a week. Tech-forward students who had served on an advisory committee for the Drexel Microcomputing Program founded DUsers, on organization that helped train other students and served as a liaison to the administration.

Publicity about Drexel’s program prompted pleas for help from peer institutions. The University received so many requests that the Drexel University Microcomputing Program Working Paper Series was created to share white papers, faculty-penned essays and the results of a five-year longitudinal study.

Drexel’s initiative also resonated among employers, with some of the country’s biggest accounting firms informing the University president that they would require first-year accountants to own a computer.

About a year after the Macintosh distribution, Drexel hosted a black-tie, red-carpet premiere of “Going National” in the Mandell Theater, which Steve Jobs attended.

A Force for Innovation in Teaching

Courtesy of Drexel University Archives

Drexel was dubbed “the Macintosh capital of higher education” by PBS in 1990, at which point there were about 14,000 Macs on campus. Faculty continued to give on-campus presentations and brown bag seminars. Publishing a new program was on par with penning a scholarly article.

The University demonstrated innovation with computers in other ways, beginning to offer online courses in 1995 and starting one of the country’s first fully online degree programs — the MS in information systems — a year later. Drexel had become fully wireless everywhere on campus except the dorms by 2000, when it was the first university to provide free voice-recognition software to students. In 2002, Drexel earned another “first” after launching a mobile Web-portal service to access grades, schedules and other alerts.

Over time, the University broadened its reach, providing communities off campus and around the world with access to technology.

In 2012, TechServ, a student organization determined to bridge the technological divide, began hosting “Community Genius Bars” that continue to this day. The organization refurbishes old and donated laptops, distributing them to local organizations and community residents. In 2023, TechServ donated more than 100 computers to organizations including The Center for Returning Citizens, which helps people reenter society after incarceration. It expanded to international projects, donating 15 laptops to start a secondary school’s computer lab in Tanzania through a Drexel Intensive Course Abroad, with plans to furnish additional computers for a school in Liberia.

Drexel invested the equivalent of $22 million to update its campus technology infrastructure, creating computer centers and training classes.

In 2013, Vice Provost for University and Community Partnerships Youngmoo Kim, who is the founding director of Drexel’s Expressive and Creative Interaction Technologies (ExCITe) Center, was recognized as an Apple Distinguished Educator. That year, Drexel University Libraries became the third university on the East Coast to dispense MacBooks for in-library use after hours.

In 2020, the ExCITe Center was designated as one of three organizations to improve digital inclusion for residents of West Philadelphia through the city’s Digital Navigator program. Members assist with in-person skills training and programming at the Beachell Family Learning Center’s KEYSPOT computer lab at Drexel’s Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships.

The University’s pioneering computer mandate has even become the subject of classes, such as the “History of Games” course taught by Tony Rowe, associate teaching professor in the Antoinette Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. Studying the history of personal computer games and the evolution of personal computers, students are prone to express surprise and intrigue when learning about Drexel’s synergy with Apple, “and hopefully become a little proud,” Rowe adds.