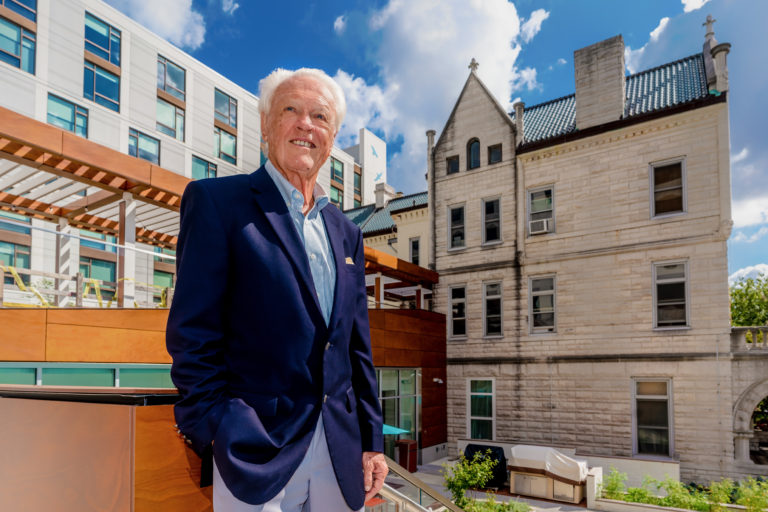

Stan Lane ’61, outside the recently expanded flagship Ronald McDonald House in West Philadelphia.

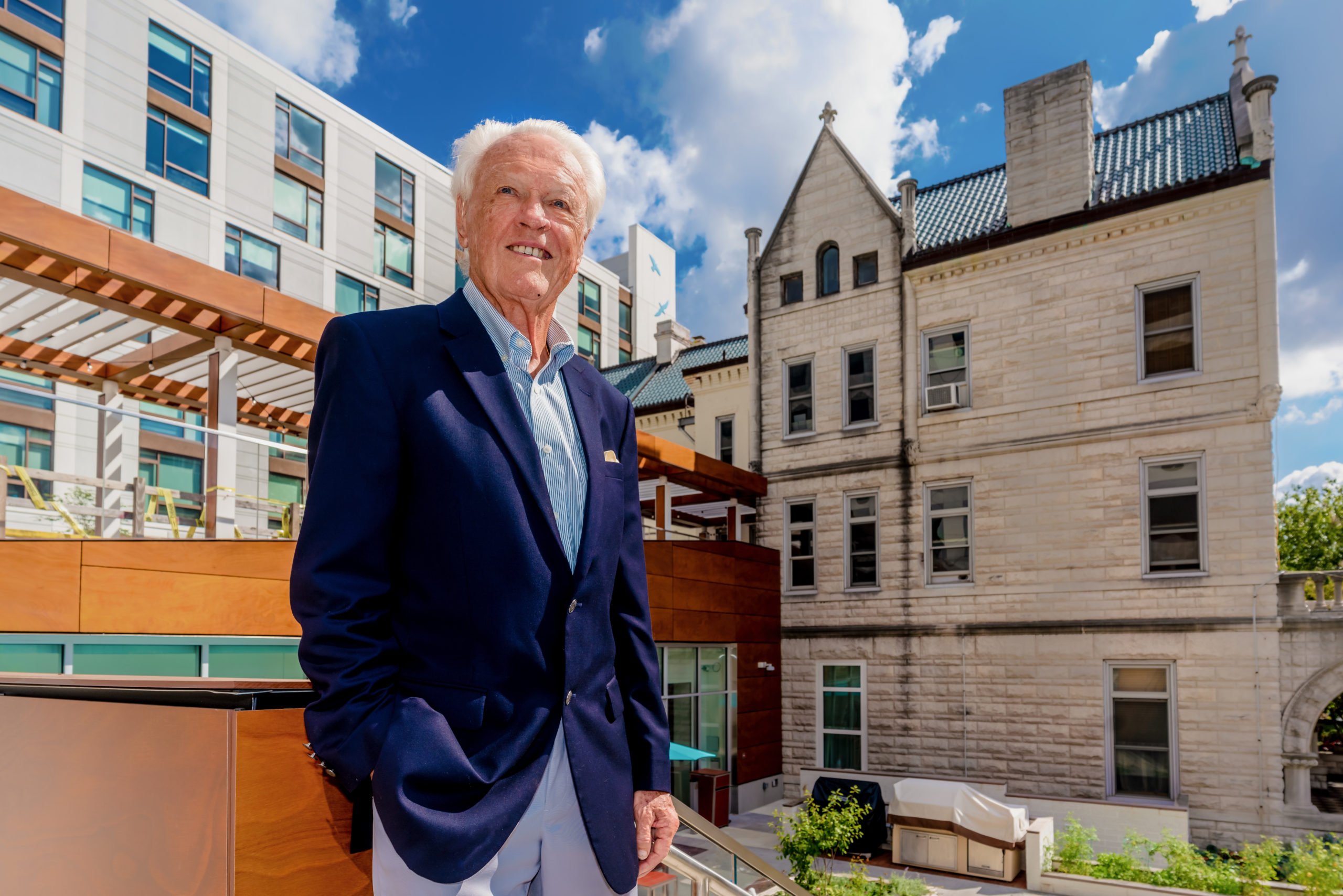

The Wilson family of six, all smiles, press around Stan Lane ’61 for a photo while he visits the Ronald McDonald House at 39th and Chestnut streets in University City — as if he’s a VIP.

In a way, he is.

During the 1970s, Lane played a crucial part in helping to establish this, the very first Ronald McDonald House, where families of sick children live temporarily while getting treatment at the area’s renowned pediatric hospitals. In 2019, the Ronald McDonald House Charities of the Philadelphia Region celebrated its 45th anniversary and an expansion that nearly tripled capacity at its flagship location.

Lane’s involvement in the charity’s origins began over pick-up basketball, where he cemented a friendship with a former Philadelphia Eagles football player whose little girl suffered from leukemia; it includes a fundraiser fashion show with fur coats; a memorable road trip to New York City; and a cobbled-together collaboration between a visionary cancer doc, McDonald’s marketers and Eagles’ executives. Through it all, Lane’s can-do optimism and persistence, by all accounts, inspired these unlikely comrades to lay the cornerstone for an international circle of sanctuary homes for medically needy families.

“I had healthy children,” says the 81-year-old father of three who’s semi-retired from his New Jersey insurance business and now makes his home in Naples, Florida. “Somehow, God gave me this motivation to keep driving and pushing this thing down the street. …You only have to take rounds with a doctor once on a leukemia or cancer ward to get hooked on trying to help kids less fortunate than you.”

The white-coifed, trim Lane looks dapper in gray slacks and a blue blazer with a yellow pocket square. At 6-foot-3-inches, he towers over parents Joe and Stephanie Wilson, each juggling a 6-month-old twin, and the older children, Carmella, 4, and Clark, 6, both grinning wide, Clark sitting in a Little Tikes coupe.

The Wilsons are staying at the house yet again, this time for a follow-up visit for Clark. The gray-eyed boy with blue-framed glasses was diagnosed with retinal blastoma, a rare type of eye cancer, when he was only 4 months old. He lost his left eye to the disease when he was 3.

Now healed, Clark still makes visits to Wills Eye Hospital and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for annual checkups. Each trip is a 500-mile, round-trip sojourn from the family’s home in Greenville, a small town in western Pennsylvania, to the Philadelphia hospitals with experts in the boy’s cancer.

Stan Lane poses with Ronald McDonald House tenants Joe and Stephanie Wilson, with their six-month-old twins, daughter Carmella, 4, and son Clark, 6. When Clark was treated for eye cancer at age 3, the family would make the 500-mile roundtrip to Philadelphia as many as 25 times a year.

“One year, we had to make 25 trips for various treatments and relapses,” says Stephanie, who left her job as development director for a Catholic school when Clark was undergoing chemotherapy. (Joe works in his family’s decorating and painting business.) “I remember one August, we were literally driving back and forth every week.”

The house provides a place for the family to stay and eases the financial burden of costly hotels and meals out. Without it, “we would be buried in debt,” Stephanie says.

That the Wilsons can count on the Ronald McDonald House is thanks to many, many generous people, but arguably one of the most important is Lane, who helped raise funds in those early days through Eagles Fly for Leukemia (EFL), the still-kicking nonprofit he founded more than four decades ago. The Ronald McDonald House has since grown to more than 375 houses in 45 countries that serve more than 7 million families — a tangible legacy of the lifetime Lane has spent making a difference.

“Stan Lane was the lane to starting the whole McMiracle,” proffers Jimmy Murray, a former general manager for the Eagles who worked with Lane on raising funds and co-founded the Ronald McDonald House. “He was vital.”

Certainly, the Wilsons are grateful for the house, where they draw strength from other families in residence. Of all the ups and downs, the remissions and relapses, the ultimate heartache came when Clark had to have his left eye removed in 2016.

“The day before Clark lost his eye,” Stephanie says, “another retina blastoma family was here that we had met on previous trips. I have a picture of their little boy. He and Clark are sleeping in the bed together.

“His mom and I stayed up and are talking in the room,” she continues, “and I still get choked up, when I look at that picture, that we were able to make that relationship and spend the night before a very hard day and a brutal moment in his treatment with another family that really understood and got what you’re going through.”

Sitting nearby, Lane says that experience captures the essence of the house. “It’s a support system,” he adds, simply.

“It’s people helping people,” echoes Susan Campbell, CEO of Ronald McDonald House Charities of the Philadelphia Region, which also includes a North Philadelphia location, “and it really speaks to the power of community, the very spirit of what the Ronald McDonald House was built on.”

***

In the early 1970s, Lane lived in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, and he often played basketball at the local gym with his neighbor. That neighbor happened to be Fred Hill, a former tight-end for the Philadelphia Eagles. That’s how Lane learned about the plight of Hill’s cute, dark-haired girl, Kim.

In 1969, when Kim was 3 years old, she was diagnosed with acute lymphatic leukemia. Doctors gave her six months to live. “That was tragic,” says Hill, 76, who now makes his home in San Juan Capistrano, California, with wife Fran. Kim was put on chemotherapy and went into remission, Hill says, but the treatments continued for three-and-half years, taking a toll.

“We just tried to survive,” Hill says. “You never thought of fundraising. When a child is sick like Kim, it affects the whole family. It’s like the whole family is sick.”

By 1972, the injury-plagued Hill had quit the football franchise. Even though he was no longer on the field, he was approached about raising funds for leukemia. One idea involved a fashion show with Eagles’ wives modeling a local furrier’s coats and a raffle of a fur.

Overwhelmed, Hill mentioned his concerns about pulling off the fundraiser to Lane during one of their pick-up games. Lane may have been “rough” on the court, leading to some “heated battles,” as Hill remembers it, but he was a true gentleman and friend when it came to this. He offered to help.

The first time Lane came over to the Hills’ home to talk plans, Kim was sobbing. She had lost her wig. “She didn’t want to come down without her hair,” Lane recalls. “I went upstairs and played the game, ‘Let’s Find a Wig.’”

Fred Hill recalls the same story — as evidence of the kind of guy Lane is. “He really fell in love with Kim,” he says.

Lane was a fount of ideas. Soon, the fashion show included signed footballs to add to the raffle and tables with a favorite player.

With the support of then Eagles’ owner Leonard Tose and the team, the event raised about $9,000. The Eagles committed to an even bigger fundraiser.

Meanwhile, with a check in hand, Lane persuaded Hill to drive to New York City to present it to the leukemia charity. During the visit, Lane, who studied business administration at Drexel and was ever the businessman, asked how the money would be used. When he learned how much would be expended on routine overhead, he became determined to donate future funds directly to Philadelphia researchers and hospitals.

Lawrence Naiman, Kim’s doctor at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children (acquired by Drexel and Tower Health in late 2019), was approached as a possible recipient for the funds. To everyone’s surprise, Naiman demurred, saying the need for funds was greater at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), where a new pediatric oncology unit was being established.

Enter Audrey Evans, a dynamo of a pediatric oncologist and CHOP’s first chair of oncology. Lane describes his recollection of a meeting he and Hill had with her, where they mentioned they were working with the Eagles to raise money:

“She didn’t know the Philadelphia Eagles from Philadelphia pigeons,” Lane quips. “She was obviously a dedicated professional.”

Indeed. Evans knew what she needed to help children with cancer. As she listed items — an isolation room, an endowed chair, and more — Lane took notes on a slip of paper that he has kept to this day. The last request, he says, was a six- to eight-bedroom home where families, who often travel miles, could stay while their children underwent treatment.

Everything on the list amounted to a hefty price tag, but Eagles owner Tose did not blink, pledging to help with it all, the story goes. At a 1973 Sunday game, plastic containers with slits were passed around for donations. More than $20,000 was raised.

Lane and Hill remember unfolding a zillion dollar bills in the basement of Veterans Stadium. “The money was a foot high in some areas,” Hill says. “Took three days to count.” A radio-o-thon and the fashion show brought in another $30,000.

With that kind of money, Lane realized he needed an official charity to handle donations. That same year, in 1973, he established Eagles Fly for Leukemia, which was recognized as a philanthropic arm of the Eagles.

Meanwhile, Murray, who was the Eagles’ point person for the charity, connected with a pal at McDonald’s. As it happened, the fast-food chain was looking for a way to promote a new product: the green Shamrock Shake. The company agreed to donate the proceeds from shake sales to benefit the house. In return, McDonald’s asked that the house be named after its mascot, the clown Ronald McDonald.

The first Ronald McDonald House opened Oct. 15, 1974, right here in Philadelphia adjacent to Drexel’s University City campus.

“That little girl was the inspiration for the perspiration,” Murray says, and Eagles Fly for Leukemia was “the mustard seed that grew into the McMiracle.”

A 2019 expansion nearly tripled capacity at the charity’s flagship location in University City. On the ground floor, families can eat meals cooked by volunteer groups, grab meals to go or cook in the new family kitchen..

Adds Hill: “If it wasn’t for Stan Lane, we probably wouldn’t have done the fashion show. We needed that guidance. I was real shy. Stan wasn’t. I would never ask anybody for a penny. Stan would.

“He was the organizer,” he continues, “and the businessman.”

At Drexel, Lane was a doer, as well, organizing pep rallies for the varsity basketball team and later founding Drexel’s South Jersey alumni chapter.

He credits his co-ops — in accounting at a chemical company, in labor management at a shipyard, in research and marketing at a brewery, in banking — for not only helping him afford college but building a vital skillset. “You meet a lot of people in all those different jobs,” he says. “I developed a lot of good people skills.”

After graduating, Lane spent two years in the Army, came out as a first lieutenant and joined the insurance business, eventually heading Lane Financial.

Fast forward a few years. By the mid-’70s, Eagles Fly for Leukemia was supporting Evans’ pediatric cancer program at CHOP and families with cancer-stricken children. The nonprofit, which parted from the Eagles to become an independent charity in 1991, has helped more than 2,000 families pay for non-medical expenses through its Family Support Fund, says its website.

“We pay bills for mortgages,” says Lane, who is the charity’s emeritus president. “We pay bills, unfortunately, for funerals.”

The organization also sponsors a Zoo Night for Ronald McDonald House families. The bulk of its funds — more than $12 million — has gone to support research in leukemia and other childhood cancers at area hospitals. Lane did not forget his alma mater. Eagles Fly for Leukemia has awarded more than $5 million in college scholarships to pediatric cancer survivors, including two full scholarships a year for studies at Drexel.

Such longevity for a relatively small nonprofit run entirely by volunteers is unusual — and perhaps more than anything a testament to its founder.

“The story began with Kim Hill, a small child fighting leukemia in the 1970s,” says Lauren McKenna, Eagle Fly for Leukemia president and a partner at the Philadelphia law firm Fox Rothschild. “It’s been at least 40 years since then. Those same principles that guided Stan in supporting Kim Hill expanded to support other families and then research. He has never wavered.”

Campbell, the CEO of the two local Ronald McDonald houses, describes Lane as a confident businessman who’s “driven, and he gets an idea in his head and doesn’t let it go.”

But she also sees a deeper motivation. “Dr. Evans’ philosophy was that you have to take care of the entire family to enable them to heal and support the sick child,” Campbell says. “When I think of Stan, I think of the fact that Fred Hill was his neighbor and he saw what that family went through. I think it’s an awesome example of Dr. Evans’ general philosophy that a sick child is a sick family, and that you have to figure out how to support families.”

***

Last year, Lane visited Philadelphia to tour the new, 93,000-square-foot tower at the flagship Ronald McDonald House on Chestnut Street. “I was so moved,” he says, “to see such a beautiful addition.”

The new space has a rooftop garden, a lending library with books for all ages and a laundry facility on each floor. The 104 bedrooms are filled with light. On the ground floor, families can eat meals cooked by volunteer groups, grab meals to go or cook in the new family kitchen, and children can play in indoor and outdoor spaces.

As Lane looks back to the house’s humble start, he says, “[I] never thought it would reach millions of kids and families. Shoot. It’s amazing.”

Then he adds: “I really believe everybody down deep inside wants to help somebody somehow. They just have to be asked.”

Donor support to The Co-op Opportunity Fund provides the resources for stipends so students can accept unpaid opportunities to follow their passions.