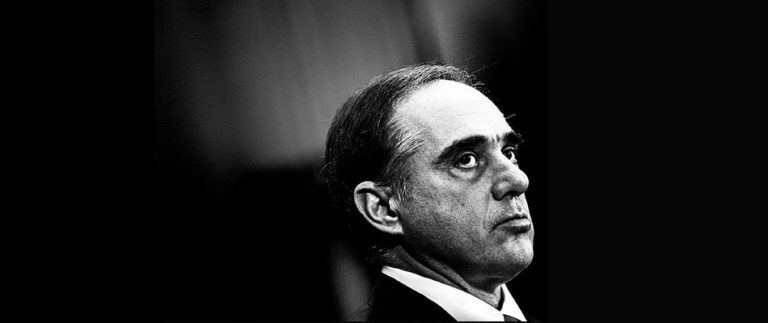

David Shulkin’s book, “It Shouldn’t Be This Hard to Serve Your Country” (PublicAffairs, Oct. 2019), is a detailed personal account of what it was like to serve in President Donald Trump’s cabinet as ninth secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs — a post that ended 13 months later with a Trump tweet.

In his book, Shulkin describes feeling pressure to please “the Mar-a-Lago crowd,” particularly Trump pal Ike Perlmutter, chairman of Marvel Entertainment. He watched his work undermined by political appointees who viewed him as an obstacle to privatizing Veterans Affairs. Eventually, his reputation suffered when news media grouped him in with officials accused of misusing taxpayer money (less publicized was the report that cleared him).

Readers, however, may conclude that he is exactly the kind of person government needs — especially now, with the world hostage to disease. A physician trained at the Medical College of Pennsylvania (now part of Drexel’s College of Medicine) with experience running major hospital systems in New York and New Jersey, Shulkin entered public service with a pragmatic desire to make government work for its constituents. His wide-ranging career includes serving as co-chair of Drexel’s Department of Medicine and, later, as vice dean of the College of Medicine. He served Obama as undersecretary for health at Veterans Affairs before being recruited by Trump’s campaign, and he is Trump’s only cabinet pick to be unanimously confirmed. During his time at Veterans Affairs, he eliminated long wait times for 57,000 veterans with urgent needs, instituted same-day services at every V.A. facility, expanded telemedicine and improved accountability across the national system.

He wrote this book to warn that political culture is becoming so “toxic, chaotic and subversive” that it is no longer easy for anyone in government to do their job. And regardless of whether one sees government as a benefactor or an intruder, times like these are when national leadership matters.

“I think everybody is rooting for the President and the administration to lead us through this crisis,” Shulkin told Drexel Magazine, “but a President and an administration are only as good as the people who surround them.”

Drexel Magazine spoke to Shulkin on March 24, soon after stay-at home orders went into effect for southeastern Pennsylvania, as he was sheltering in place at his Gladwyne home with wife and fellow 1986 MCP graduate Merle Bari, MD, and his two grown children.

Shulkin and his family with President Obama on Veterans Day in 2016.

Q. What was your first thought when it became clear that a pandemic was heading our way?

I think I was hoping that we would have people in charge doing what was necessary to prepare.

Q. Did we? How do you rate the United States’ handling of the pandemic in the first 100 days?

No. Clearly the biggest issue is that we weren’t ready with diagnostic testing. Once we fell behind in the ability to test we had to essentially assume a worst-case scenario. That created fear and potentially reactions that didn’t fit the situation.

It now appears that we’re getting a better handle on the community spread. But the challenges we continue to see are when the information being given doesn’t match reality. Like when we’re told anybody can get a test and we know that’s not the case, or when we hear mixed messages about the importance of social distancing. That’s where there are opportunities to make the government response work better for everyone.

And when it comes to research, this country’s leadership is behind that of China. If you take a look at the 45 clinical trials being run right now, 38 are in China, six are in the United States and two are being done between China and the United States. We are finally seeing new clinical trials in the United States, but we’re playing catch up.

Q. How is the United States positioned to weather this, relative to other developed countries?

I think we have both advantages and disadvantages. When you take a look at our health care infrastructure, the United States has a very sophisticated workforce and technological equipment.

But we have been shuttering hospitals in communities with low demand. As a result, we have far fewer beds than you would find in Asia or Europe. In Japan, for example, they have 12.8 hospital beds for every 1,000 people; the United States has 2.8.

On the other hand, we are seeing an incredible innovative American spirit from our health care leadership. They created up to 50 to 60 percent additional hospital capacity by converting non-clinical spaces. We’ve seen the U.S. manufacturing industry make itself available like it did in World War II to help manufacture equipment ventilators and masks and medical supplies, and this is being done in record speed.

But when it comes to social distancing and isolation, it’s not natural for Americans to limit their activity. And we’re watching the President challenge some of the scientific advice by saying, look, you know, the cure may be worse than the virus itself…maybe we need to start returning to work. And that’s in direct conflict with medical advice.

Q. Your book describes red tape, unclear directives and a kind of shadow cabinet of political appointees. Do you think these dysfunctions are so widespread they’ll impact our pandemic response?

I worry a great deal about that. During times of crisis, you need people who are competent and have expertise and experience. That’s where the people who surround the government, who lead our agencies, are absolutely critical.

What I’ve seen during this administration is a battle between those who are career government officials — who have served multiple administrations and are there to focus on the mission and the work and not participate in partisanship — and those who are clearly partisans who are much more interested in winning political arguments than in the mission. That makes it very, very challenging for people to get work done.

I think we’re seeing a little bit of that play out right now, where you see tension between the advice from medical and scientific professionals, and the advice from people interested in the politics of the country and an election coming up. Ultimately the decisions that will be made will impact people’s lives.

Q. There seemed to be a theme in your book of the Trump administration putting economic considerations ahead of the well-being of veterans themselves. Can we count on this administration to strike a reasonable balance between people’s health and the economy?

Well, I do think that the President has a legitimate point of view, which is that ultimately the unintended consequences of fighting this virus will be very significant and in many cases have long-lasting consequences.

There is going to be social isolation, which we know from past pandemics has a very high correlation with increased anxiety, depression and up to 35 percent of the population experiencing post-traumatic stress, and there will be people losing their livelihoods so that they can’t afford medications, health insurance, good food and quality care.

The problem here is this is not a decision that is one or the other. We have to address what we know works to get rid of the virus and to shorten the duration of the pandemic, and at the same time do whatever we can to lessen the economic and mental health consequences.

Q. Do you think this experience could change the national conversation about the role or value of government in our health care?

I think for sure it will change people’s view of government. Many people are just disgusted by the political games, by personal attacks, by the partisanship that has been on display every single day, and they had pretty much written off the value of government. But when a crisis like this comes along it reinforces why it is essential that we have a good functioning government that can pull the country together. A virus doesn’t differentiate by political party, by race, by creed, by religion. It shows that we are a society that’s interconnected. And I think there are signs of hope that when we come out of this that maybe people won’t be as separate from one another or as hostile.

When it comes to something like this, not having the means to be able to afford access to health care or tests or the right type of care has to be addressed, particularly by government. That’s why we’ve seen free testing come out of the coronavirus bill. That’s why we’re seeing hospitals being given subsidies in stimulus bills so that everybody in the community can be cared for. I think that speaks to the need that health care should be a right, not necessarily a privilege.

Q. You’re the highest-ranking person to serve in both the Obama and the Trump administrations. The contrast you describe between how each administration vetted and treated you is alarming, but it doesn’t seem like you wrote your book to settle scores. What was your motivation?

I didn’t want this to be a fire-and-fury book. I know that that probably would sell a lot more books. But my goal was to have a longer-lasting piece.

I want to say, look, if you’re serious about going into government, if you’re serious about helping other people, about leading large, complex organizations, here’s a book that adds a perspective that shares what that’s like. Not only what it might be like for you, but for your family.

What happened to me was an organized campaign by political appointees to spread myths and mistruths, who understand how to use the media to launch allegations that damage a person. We even found an email that was left on a copier machine where they laid out exactly their plan to get rid of my chief of staff because she was a Democrat; to get rid of my deputy secretary, because he didn’t follow their politics; to get rid of my undersecretary; to get rid of me and to replace all those people with people that were affiliated politically with their philosophy. They were successful in exactly following the plan. And that ended what I think was a great opportunity to continue the successes that we were having in fixing Veterans Affairs. It didn’t really matter whether the accusations against me were true or not. Because if media runs with them and there isn’t a forum to get the facts out, people assume they’re true. I wrote this book to lay out the facts of everything that happened and let people make up their own minds.

I also go into detail to share what happened to me to let people know how the current government is operating. If we do not reset the environment in which one serves, we’re not going to get the type of people whom we need in government.

Q. The President was praising you right up to the end, yet no one intervened to rein in the political appointees who opposed you. Deep down, do you believe that Trump was sincerely on your side or was he tacitly on board with those who want to privatize Veterans Affairs?

I don’t think the President was always aware of these people or their agenda. They are not visible to him. There are 4,200 of these political appointees dispersed throughout various agencies. I believe that some of these people were much more zealots in terms of their political partisanship and their political philosophies than the President himself.

Every President has a different version of this. What we’re seeing in this administration is not necessarily new territory, but we’re seeing that political loyalty is being given a much higher priority in who gets to sit around the table than necessarily competence at the job. That becomes clearest in times of crisis.

But that doesn’t mean that the President doesn’t want to do well for the country. It’s just that if you have people around you who are more concerned about politics than substance, it creates problems.

Q. How have veterans been served by all of this? How should they feel about the policies of the past several years?

I think Veterans Affairs is in a much stronger place now than it was when I entered government in 2015. And for a number of reasons, the leadership who replaced me at Veterans Affairs has continued to follow most of the initiatives that I started, and I’m pleased that they’ve done that.

Also, there’s an unwritten rule that when you leave government or when you’re fired, that you should go away and stay silent. And I just never signed up for that.

I spoke very publicly about my concerns about privatization. I think that lent some transparency so that Congress was able to put the Trump administration on the defensive to where they had to deny that that was their intent. I think that if I had gone away quietly we’d be seeing a very, very different picture today.

But I’m also realistic that if we take our eyes off the ball, there easily could be very strong efforts mounted to dismantle this system.

WHEN A CRISIS LIKE THIS COMES ALONG IT REINFORCES WHY IT IS ESSENTIAL THAT WE HAVE A WELL-FUNCTIONING GOVERNMENT THAT CAN PULL THE COUNTRY TOGETHER.

Q. Why do you think it’s important to keep the Veterans Affairs health care system intact?

The system serves a very specific population of 9.5 million wounded veterans with conditions that require specialized expertise that is not readily available in the private sector, and it’s the only place that delivers care in a way that honors their military service.

In addition, it trains more doctors, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists and social workers than any other health system in the country. If it went away as a training site, the rest of the country would have a deficit of qualified health care professionals. It also does close to $1 billion of research every year that has led to amazing medical advances that Americans rely on, such as the hemodialysis machine, the first lung transplant and liver transplant in the country, the cardiac defibrillator, the association that an aspirin a day prevents heart disease, and the CAT scan.

And then there is the fourth mission of Veterans Affairs, which we’re seeing right now in this pandemic, which is that as the nation’s largest health care system, it’s a backup for the country.

When there is a national disaster, Veterans Affairs has more hospitals, doctors, nurses and facilities than anywhere else and it is capable to step in and help.

Q. You’re a member of a large club of people fired by the President. The Brookings Institution’s tally of turnover among Trump’s executive office puts it at about 86 percent as of May 15, 2020, not even including cabinet secretaries. How should we feel about this?

On the day my book was released, I was supposed to be on many national network shows. I got bumped from them all because it was the exact day that the impeachment inquiry started.

In that context you were seeing career officials such as the Ukraine ambassador Marie Yovanovitch in the Congressional hearings talking about why she did her job, what she was focused on, how she took this so seriously. And then you had the administration officials saying she was unfit, she was a disaster and had to be removed from office.

Well, that was an analogy to what I experienced in government. And here in the pandemic again: It’s so important that you have people who actually are experienced and are competent.

I think that we have to be concerned. We have to be concerned that people be placed in their jobs because of their experience and the skills they possess. I think many of us are comforted when people like Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who are world experts and have been through multiple administrations, are given a strong voice. But I think we have to watch whose advice the administration and the President ultimately takes. And, you know, this is still very much uncertain as we talk today.