When a crisis hits, everyone looks for the cavalry. This spring, it wasn’t Washington, D.C., or the Army Corps or the National Guard. Instead, almost immediately, ordinary people stepped up. Our tremendous community of faculty, staff, students and alumni leapt into action, bringing information, aid and gear to those impacted.

We learned of alumni who were pitching in to provide food, economic aid and emergency medical supplies to the city. On campus, students collected supplies and created resources to keep others informed and connected. Meanwhile dozens of faculty members launched new COVID-19 research projects, with 17 faculty awarded fundings for diagnostics, devices and scientific studies that promise to save lives and advance our understanding of the virus.

Though we selected 19 stories to share in Drexel Magazine, many more went untold. Here are some of the Dragons who answered crisis’ call in the early weeks of the pandemic.

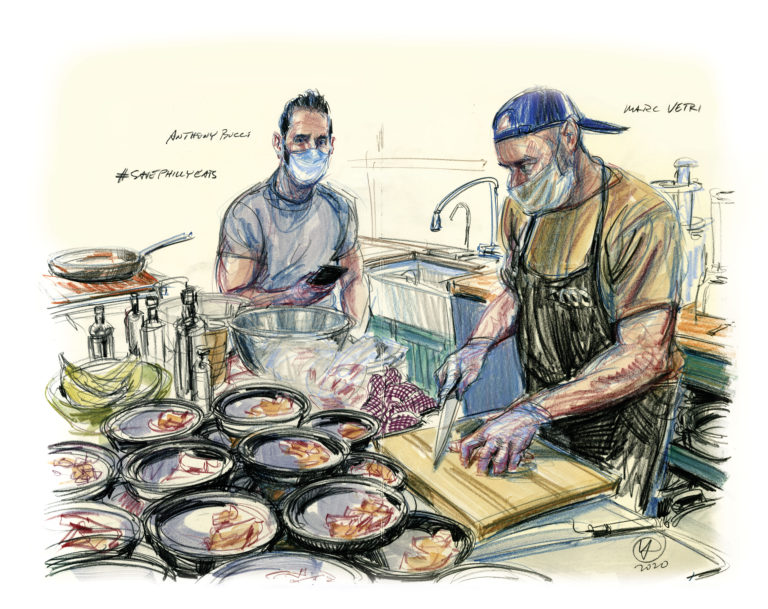

1. Anthony Bucci et al.

Philadelphia’s roster of delectable BYOBs and independent eateries is among the jewels that make this town great. So when stay-at-home orders shut the local food scene down, local foodie Anthony Bucci (BS information systems and technology ’04) stepped up.

In just six days in March, Bucci built and launched a website to pair foodies with unique dining experiences offered by local chefs. The “buy now, feast later” concept, called #SavePhillyEats, gave restaurateurs the cash they needed immediately to pay staff, bills and rent — a big deal in a city where restaurants are 19 percent of the businesses and 10 percent of the jobs, according to the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia.

Within 10 days of going live, #SavePhillyEats was working with more than 50 restaurants and bars and had helped them generate funds of $150,000 to $200,000.

“I have friends in the Philadelphia restaurant community, and the city has a wonderful and vibrant food culture which is a big part of Philly and Philly’s culture as a whole,” said Bucci, who made his name as the founder and former CEO of multi-million dollar motorcycle equipment and apparel website RevZilla.com.

Bucci enlisted several friends to bring his idea to fruition, including fellow Drexel alumni Chris Cashdollar (BS ’99), who provided web development and branding services, and Dustin Carpio (BS ’07), who handled video, content and live production needs.

One of the first restaurateurs to join the website was Bucci’s friend and fellow Drexel grad Marc Vetri (BS marketing and finance ’90), owner of Vetri Cucina and Fiorella Pasta. Vetri offered bonus gift cards as well as an intimate, multi-course chef’s-counter experience worth $10,000. The funds allowed him to continue to pay his salaried staff and provide health care benefits after his businesses closed.

“It’s a great way for a customer to help and not feel like they are just donating money,” Vetri said of #SavePhillyEats. “They are actually buying something significant — a win-win for all parties involved.”

On Easter Sunday, chefs involved in #SavePhillyEats paid it forward by providing holiday meals to about 3,500 health care workers at hospitals and testing sites.

“It’s everyone’s time to help right now,” Bucci said, “especially those of us in unique positions to amplify or create additional support structures.”— Beth Ann Downey

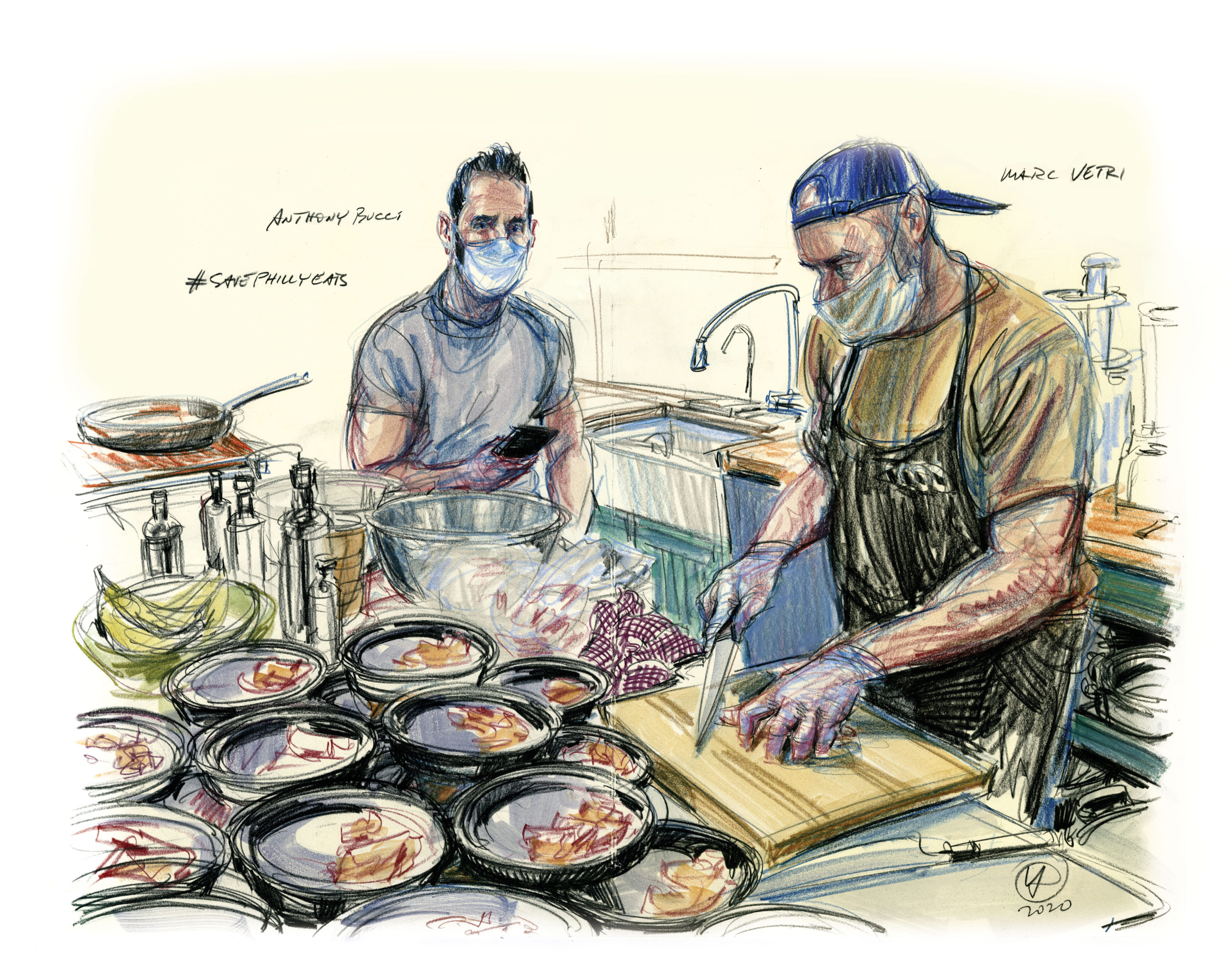

2. Grant Geiger & Patrick Fenningham

In normal times, Philadelphia-based EIR Healthcare produces prefabricated hospital rooms for rapid installation in new hospitals.

But EIR Healthcare’s modular hospital rooms can also function as mobile units to treat patients in a pandemic. They can even be built as negative-pressure chambers, the gold standard in isolating infectious patients.

“If I manufacture patient rooms for a building or I manufacture something temporary…it’s essentially the same product,” said CEO Grant Geiger (BS/BA international business administration and marketing ’11), who runs the company with Chief Product Officer Patrick Fenningham (BS biomedical engineering ’11). “The only difference is where it’s going. Instead of a building, it’s going into a convention center or a gym.”

When the coronavirus outbreak reached the United States, EIR Healthcare quickly partnered with three different manufacturers to ensure they could step up their production capability from just a couple of units a week to as many as 75. They entered discussions with officials from the University of Pennsylvania, Montgomery County in Pennsylvania, Bergen County in New Jersey and even the government of Kazakhstan.

Other cities have grappled with surges of COVID-19 patients by rapidly erecting emergency field hospitals. In Philadelphia, the Liacouras Center at Temple University was outfitted to take in up to 180 patients who were in the final stages of recovery. Even Drexel’s Athletic Bubbles are on standby if needed.

Should the situation become dire in Philadelphia — or anywhere else — EIR Healthcare is ready.

“What we’re trying to do is make sure that this is bigger than business,” said Fenningham. “This is really talking about people in a life-or-death perspective.” — Jen Miller

3. Karen Verderame

When the city went into lockdown, almost everyone brought work home with them. For Karen Verderame, that meant bringing home several colonies of hissing cockroaches, a couple of testy tarantulas and some centipedes.

As animal programs developer for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, she led a team of essential personnel who cared for the museum’s collection of hundreds of live animals and insects when the museum closed on March 13.

“Once the shutdown was initiated, we went into complete triage mode,” Verderame recalled. There were contingency plans to activate, vital information to share, safety measures to put into place, work schedules and feed shipments to manage, and worst-case scenarios to prep for.

Thanks to her work, the many creatures depending on her team — 14snakes, 13 turtles and tortoises, 10 lizards, three frogs, five rabbits, three armadillos, two guinea pigs, two ducks, two turkey vultures, one chinchilla, numerous live invertebrates and a variety of fish — will survive to see the return of class field trips. — Beth Ann Downey

4. Charles Cairns

The idea of using phone apps to track infections may make Americans uneasy, but there’s no question that tracking technology helped quell outbreaks in China, Singapore and South Korea.

Here in the United States, Apple and Google are developing a cell phone beacon for instantaneous contact tracing, but full capability is reportedly months away.

In the meantime, there’s the Drexel Health Tracker App, released in April. The app was developed by a team of collaborators led by Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Dean of the College of Medicine and Senior Vice President of Medical Affairs Charles B. Cairns, MD. It allows University faculty, staff and students to monitor their symptoms and receive urgent health alerts from the city and the University. Dragons can use the app to follow outbreaks of the SARS-CoV-2 virus over time and across locations. The developers see the app eventually being adopted and customized by other academic and medical institutions. — Alissa Falcone

5. Evan Ehlers

When Philadelphia ordered all non-essential businesses to close, thousands of pounds of food that had been destined for city restaurants were suddenly doomed for a landfill.

Or they could have been if not for Sharing Excess, a food-reallocation nonprofit run by Drexel alumnus Evan Ehlers (BA entrepreneurship/entrepreneurial studies ’19).

During the first two weeks of the outbreak in mid-March, Sharing Excess staff worked 14- to 18-hour days, making about 50 pickups to its food service clients to rescue nearly 30,000 pounds of food (safely, with donated bulk bottles of hand sanitizer and latex gloves). That’s about 10 percent of Sharing Excess’ entire food donation haul over its two years of existence — in just 14 days.

Ehlers founded Sharing Excess in 2018 as a way for college students to donate unused portions of their campus meal plans, but it has grown to include 40 food service partners and seven university chapters that rely on Sharing Excess to redistribute their surplus food.

“We’re the fast, convenient, agile delivery service that can take leftover food from any grocery store or restaurant and deliver that to a hunger relief organization or community center in about 30 minutes or less,” Ehlers said.

As the pandemic response evolved, the city asked Sharing Excess to help move food from food banks like the Share Food Program and Philabundance to one of about 40 distribution sites citywide where households could pick up a box of food, free to all, no questions asked.

“This is definitely a really dark time for a lot of people,” Ehlers said. “But I think it’s really important that we all see the possibilities that can happen when we all come together to collaborate.” — Beth Ann Downey

6. Geneviève Dion

Just last September, Drexel’s Pennsylvania Fabric Discovery Center at the Center for Functional Fabrics relocated into a state-of-the-art research facility at 3101 Market St. to develop next-generation functional textiles and original products. When the pandemic arrived six months later, the center’s 3D knitting machines and cutting-edge prototypes became a lifeline to front-line workers in need of filtering masks.

Inside the 10,000-square-foot, $7 million space, Director and Professor of Design Geneviève Dion rapidly assembled a team of six to move two mask prototypes — one for health care providers and one for the public — into 24/7 production, compressing years of R&D into a few weeks.

Within 24 hours of deciding to take on this project, Dion had the center reclassified as essential. A few days after that, she was already reviewing an initial design with College of Medicine colleagues. Within two weeks, the designs were in production, and by week four, her team had made about 1,200 washable, adjustable masks.

Dion estimates the masks are nearly as effective as respirators, though there has been no time for FDA testing. “The feedback we’ve received indicates that we’re close,” she said. “But you don’t want to make false claims for a product, especially one that people’s lives depend on.”

Dion’s target is to make 10,000 masks every six weeks, for as long as needed. She’s proud of how the young innovation center, which was created with public funds to revive the region’s textile and garment manufacturing, has proved itself capable of a rapid response.

“The center was designed with that in mind, but it’s rare to have the opportunity to fully demonstrate it,” Dion said. “This emergency has forced us to show what we can do in a short amount of time.” — Beth Ann Downey

7. Scott Knowles

Drexel Department of History head Scott Knowles’ first thought when the pandemic arrived was to do what he always does as a disaster historian: call up experts to find out more. After all, it’s what he did after 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina.

His second thought, though, was to do something completely new: broadcast his calls to the public and archive them for posterity.

On March 16, Knowles began hosting live discussions, referred to as #COVIDCalls, every weekday at 5 p.m. with historians, journalists, professors, researchers and other experts and professionals who could shed some light on the pandemic. Topics range from emergency preparedness, virus testing, grief, crime rates, rural health, past pandemics and disaster response, just to name a few. The recordings are available at Soundcloud.

Knowles wanted to paint a picture of what was happening not only in America, but around the world, where other experts were watching the crisis unfold in their home countries.

“Part of my research is about communication in disaster, so I’m literally doing that work in real time,” said Knowles, who in 2011 published “The Disaster Experts: Mastering Risk in Modern America.”

Along the way, this has been a once-in-a-lifetime chance to promote his field. “We do not have great capacity in the United States for multi-disciplinary disaster research, but I want to show that there is a community that can come together, and when their voices get together, it’s pretty powerful,” said Knowles. “I’d like to see something like a Union of Concerned Scientists, but for disaster. Can I do that with a daily one-hour webinar? No. But can we use this as an opportunity to build a stronger community of researchers? Absolutely!” — Alissa Falcone

8. Alexander Fridman

As scientists around the world began raising concerns that SARS-CoV-2 could remain airborne longer than previously believed, Drexel researchers were already dusting off an air sterilizer they built more than 10 years ago to combat anthrax attacks after 9/11.

The device is a filter created by College of Engineering Professor and Director of Drexel’s C. & J. Nyheim Plasma Institute Alexander Fridman. It was proven to be more than 99 percent successful at removing anthrax spores from the air.

The filter uses cold plasma — air particles activated by electrical pulses — to blast apart airborne chemical contaminants and bacteria. The researchers speculate that forcing air through a grid of cold plasma could deactivate viral particles. Though coronaviruses are smaller than bacteria or anthrax spores, they have some of the same structural vulnerabilities.

Researchers are now adapting it for a new use, and for possible installation in home and industrial air handling units.

The project is supported by a $200,000 National Science Foundation grant, one of the first to study ways to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 from the air. — Alissa Falcone

9. Arun Ramakrishnan, Michael Lane et al.

When calls went out in March for donations of personal protective equipment for staff in local hospitals and clinics, Dragons acted fast.

On the morning of March 24, faculty at the College of Nursing and Health Professions decided to donate the college’s unused lab supplies. That afternoon, Director of Research Labs Arun Ramakrishnan collected 700 medical masks, 200 gowns and 25 containers of liquid and foam hand sanitizers. By nightfall, everything had been delivered to local hospitals and other critical organizations.

Meanwhile, College of Medicine Associate Professor Michael Lane led staff and graduate students on a hunt for unused equipment in research labs and supply closets. By the end of March, they had rounded up 16,600 exam gloves, 743 sterile gloves, 197 disposable gowns, 550 masks (including 23 N95 masks), 150 safety glasses and one large box of Lysol wipes.

A separate group led by medical students Kira Smith and Estefania Alba reached out to local businesses like construction companies, museums, hardware stores, auto shops, nail salons, tattoo parlors, veterinary hospitals and neighboring universities. In March, they were able to donate a large supply of N95 masks and nitrile gloves and gowns to St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, which Drexel co-owns with Tower Health. By mid-April they had collected even more — totaling 39,677 exam gloves, 2,349 procedure masks, 1,114 sterile gloves, 651 disposable gowns, 345 sewn masks, 280 safety goggles/glasses, 159 N95 respirators, 62 face shields, 45 Tyvek coveralls and hundreds of miscellaneous materials such as scrubs and cleaning supplies.

Scientists and staff at Drexel’s Academy of Natural Sciences raided specimen-handling supplies to collect approximately 90 boxes of gloves, 100 masks, 30 boxes of wipes, three bottles of Purell and 420 safety goggles.

Even Drexel Sports Medicine donated masks and gloves normally used in the treatment of student-athletes to give to staff at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children. — Alissa Falcone

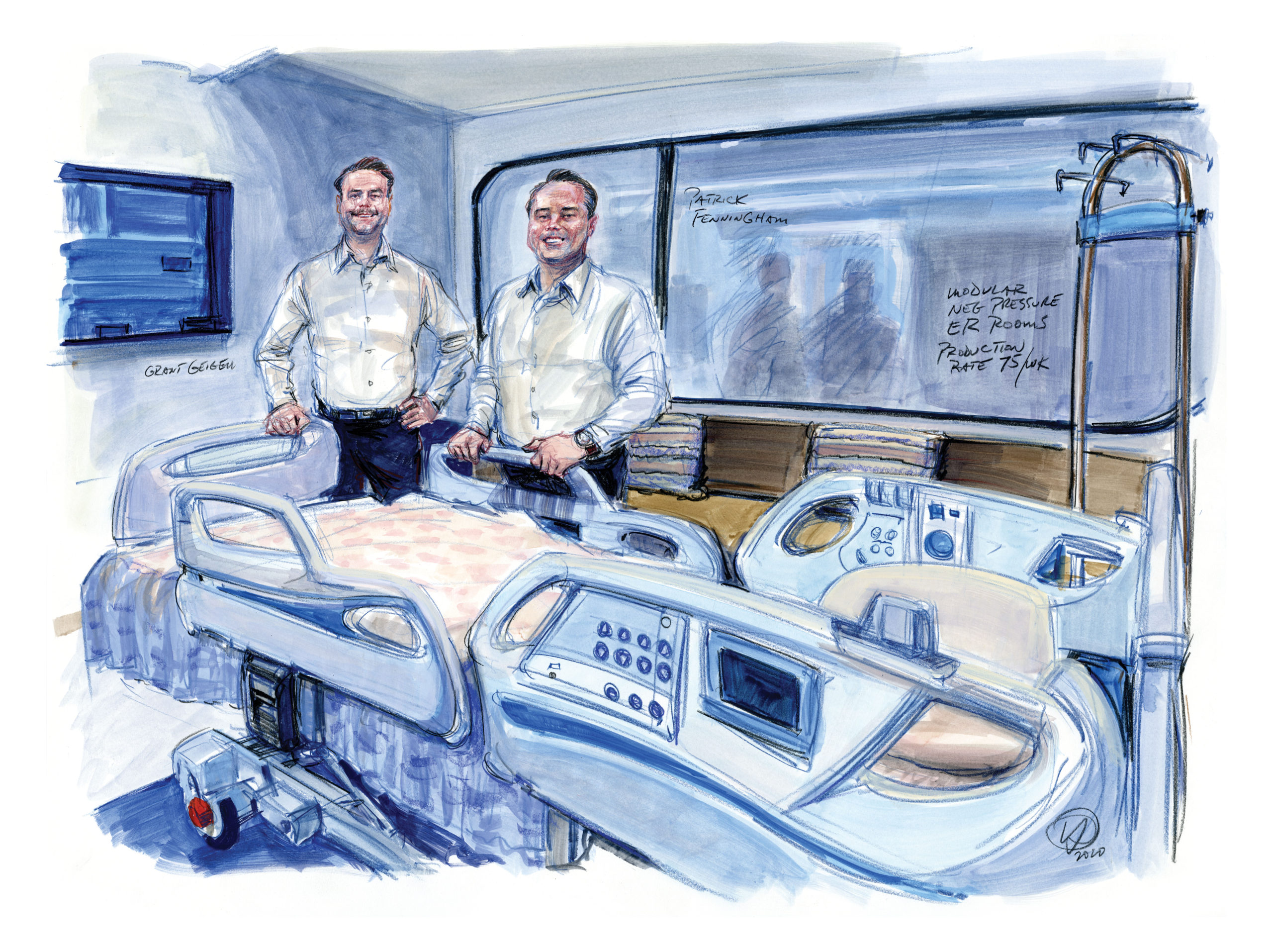

10. Chad Butters

“Capitalism only goes so far…you’ve got to think of the environment you’re in,” said Chad Butters, MBA ’14, of his decision in mid-March to convert his entire distillery to making hand sanitizer.

A military vet who majored in entrepreneurship and innovation management, Butters is the owner of Eight Oaks Farm Distillery in New Tripoli, Pennsylvania. He founded the venture in January 2016 and runs it with his family, marketing “seed-to-spirits” liquors made from grains grown on their own community farm in Lehigh Valley. Bourbon, rye whisky, vodka and gin are the core business. Or were.

With a recipe shared by the World Health Organization, Eight Oaks joined big companies like Budweiser and Kentucky’s famed bourbon makers, as well as fellow alumni Vlad ’01 and Marat Mamedov ’07, two brothers who run Boardroom Spirits in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, in stepping up to solve the sanitizer shortage.

In the first week and a half, Eight Oaks made 5,000 bottles. Soon, daily production ramped up to 12,000 bottles.

On March 15, Eight Oaks posted about the operation on its Facebook page and started taking donations to pay for glycerin, hydrogen peroxide and other materials. The story went viral, with coverage in Time, CNN, and The Wall Street Journal.

By April 7, Butters had raised $92,000 to support his effort and began donating one bottle of sanitizer for every $1 donated.

The change also allowed him to keep his 25 employees on the job.

“It boiled down to what’s the right thing to do, and the right thing to do was to flip the switch here and try to get ahead of this and make some hand sanitizer,” Butters said. — Jen Miller

11. Jared Therrien

Jared Therrien ’18 was at Target in early April when he saw something that needed fixing.

“I saw these labels on the ground,” he remembered. “They basically had a little logo of a foot and there was a whole bunch of text saying to keep 6 feet away, and nobody was paying attention to them. I thought to myself, ‘We could do this so much better.’”

Therrien, who graduated with a BS in product design and a minor in entrepreneurship and innovation, is the CEO of Emergency Information Systems (EIS), a startup he created as a student that designs labels and signage to help emergency responders find their way around buildings.

After returning from Target that day, he created the Project S•A•F•E Initiative — a set of intuitive and readable floor decals that encourage 6-foot spacing in public queues — with Nicole Feller-Johnson ’18, an adjunct faculty member in the Westphal College of Media Arts & Design, and several alumni and a student co-op.

EIS donates the labels to life-sustaining businesses and also offers a “buy one, donate one” system with paying clients. In the first two weeks, there were hundreds of orders from businesses around the country. And that’s just the start.

“We see this project and this product as being a need that’s ongoing as the CDC restrictions relax and as things reopen,” said Feller-Johnson. — Alissa Falcone

12. Michael Silverglade

“It was a weird day,” Michael Silverglade ’20 recalled of March 12, the day that restrictions on large gatherings were issued in Pennsylvania.

In the blink of an eye, the social-distancing edicts ended the fourth-year music industry student’s internship with concert promoter Live Nation at its 2,500-capacity Philadelphia music venue The Fillmore. They also demolished his senior project, which was to manage a month-long tour of his band, Courier Club, before he graduated in June.

But Silverglade and his bandmates made something great from the situation. Within a few weeks, they built a virtual music festival on Minecraft called Block by Blockwest, featuring nearly 40 bands and three stages, with proceeds from donations and T-shirt sales going to the CDC’s COVID-19 relief fund.

The band reached out to artists such as Pussy Riot and Idles, asking each to record a 20-minute live set to stream through the 3D block-building video game. Each band had a virtual stand for online merch sales, and the festival marketed an exclusive Block by Blockwest T-shirt.

Interest in the event was so intense that on the day it was scheduled, 100,000 virtual spectators crashed the server. The festival was rescheduled for May 16, when it drew nearly 140,000 viewers and raised $7,600 for pandemic relief.

“We definitely turned a bad situation into a good thing through Block by Blockwest, because now it’s probably the coolest thing we’ve ever done as a band,” said Silverglade. “I think it was a blessing in disguise.” — Beth Ann Downey

13. Micholas Smith

One of the earliest U.S. scientific studies of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was conducted by Drexel alumnus Micholas D. Smith (PhD physics ’14, MS physics ’11) and Jeremy Smith (no relation), two University of Tennessee academics working at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee.

The Smiths used IBM’s Summit, the world’s fastest supercomputer capable of 200 quadrillion calculations a second, to shortlist potential drug candidates most likely to disarm the virus, in hopes of saving other scientists precious time developing a drug treatment.

Micholas Smith began in January by building a computational model of the coronavirus’ spike protein, based on Chinese studies, and running molecular simulations. With Summit, he screened 8,000 well-characterized compounds, ranging from existing anti-fungal medicines and anti-virals to natural products derived from traditional medicinal herbs.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is shaped like a ball with spikes on its surface made up of proteins. It spreads from person to person when those spikes are able to bind to a human cell receptor called ACE2. The hope is to identify a compound that binds to those spikes, which could slow or halt infections.

“With this virus, if you hit and disrupt any of the targets, you mess up the virus,” Smith said. “If you can at least reduce the function of viral proteins, that helps.”

By Feb. 20, Smith and Smith had identified 77 small-molecules and a ranked list of the remaining library worthy of further experiments. They published their results on ChemRxiv immediately rather than wait for peer review so that researchers at other universities wouldn’t lose time duplicating the work.

Smith said that depending on the computing power available to other researchers, his work will save them weeks, at least, of calculations. His next goal is to virtually screen millions of other compounds, which he hopes will shave a few years off the search for COVID-19 treatments. — Jen Miller

14. Diane McNitt

This letter came to Drexel Magazine from Diane McNitt, 63, a 1980 graduate of Design & Merchandising. She runs a home-based clothing alterations and refashioning business in Lansdowne under the moniker “The Sewing Doctor.”

Dear Editor,

My love of sewing has been my “therapy” since I young girl. I still use the sewing machine I got as a Christmas gift when I was a sophomore at Drexel.

Despite two surgeries on my right hand and needles in my elbow, I wanted to make masks. My husband and my son cut out the fabric and the ribbons, which was a huge help, and a way for our family to help the community.

The first weekend of April I turned our home into a sewing studio — cleaned cotton fabric was draped over chairs, dining room table was turned into a cutting table, ribbons were laid out to be cut for ties, ironing board was set up in the bedroom.

Using the skills I gained from my design classes, I used materials I had on hand and made them work. I cut up my mom’s nightgowns and my son’s T-shirts to use as soft fabric on the back of the masks and used scraps of fabric from previous projects.

I also donated a ton of my buttons for the health care workers as elastic is tough on their ears from wearing their mask all day. Some have put the elastic around a button on their headband.

It’s been a blessing to help out even in a small way.

15. Marek Swoboba

Going from “impossible” to “perfect” in a two-week timeframe is hard in most circumstances, but especially when creating ad-hoc medical hacks in an emergency.

Which is why Drexel alumnus and Assistant Teaching Professor Marek Swoboda (PhD biomedical engineering ’05) was initially skeptical when the University of Pennsylvania Health System came knocking on March 25 with a tall order: Create 500 ventilators in two weeks as back-up systems in case their hospitals see a COVID-19 surge.

But within five days, Swoboda and engineers from his Princeton Junction, New Jersey, startup RightAir — which is working on ventilators for chronic lung disease patients — had a prototype of a compact, non-mechanical device called a “Y-Vent” based on 50-year-old military field medicine technology.

The Y-Vent can be 3D printed in three hours, assembled in 10 minutes with hot glue, and can be attached to a standard oxygen tank or a small air blower to deliver pressurized air to an intubated patient. Though not FDA approved, it can save lives during an equipment shortage.

“It was just a perfect solution for this purpose, and people see it,” Swoboda said.

Swoboda has since made the Y-Vent design open-source for any hospital around the world facing the impossible. — Beth Ann Downey

16. Wan and Wei-Heng Shih

A husband-and-wife team at Drexel believes that a piezoelectric sensor they developed in their lab can be used to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Professor Wan Y. Shih in the School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems and Professor Wei-Heng Shih in the College of Engineering are co-inventors of a piezoelectric sensor — piezoelectric refers to the ability of certain materials to generate an electrical charge when pressure is applied — that is already being used successfully worldwide to detect breast tumors.

For their newest invention, they have coated a very thin piezoelectric sensor with probe RNA complementary to the RNA of the coronavirus. They expect that when the viral RNA binds to the probe RNA, the resonance frequency of the sensor will shift, indicating a positive infection.

Their diagnostic, which in April received funding from Drexel’s COVID-19 Rapid Response R&D fund, will be portable, inexpensive, and easy to use, says Wan Shih. “The test takes only 30 minutes from nasal swabs or saliva samples,” she said. “It is ideal to be made widely available at point of care.” — Sonja Sherwood

17. Kelsey Clark

As she watched people’s lives upended by the outbreak, doctoral student Kelsey Clark (MS psychology ’19, PhD clinical psychology ’22) was inspired by her training as both a scientist and a clinical practitioner to do something.

She created the “COVID-19 Resource List” — a public Google document over 500 items long — to connect people with information, support and services, with a focus on mental health. (Access the resource list here.)

After publicizing the list on Twitter, she caught the attention of Psychologists Against COVID-19, a group of more than 100 psychologists nationwide, who invited her to join them in creating a central repository for pandemic-related resources.

“It has been encouraging to see how many resources are out there, and how many people are doing what they can to help,” she said. “We are all experiencing stress, discomfort and suffering… May we all be kind and compassionate toward ourselves during this time.” — as told by Kelsey Clark

18. Gail Rosen et al.

Thanks to the work of a Drexel-led team, we know that there are at least six to 10 slightly different versions of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in America, and many more worldwide.

The team studied global test results and identified mutations in the virus, using a quick-result tagging tool they developed called Informative Subtype Markers.

“This allows us to see the very specific fingerprint of SARS-CoV-2 from each region around the world,” said College of Engineering Associate Professor Gail Rosen, who lead the team that included doctoral student Zhengqiao Zhao and Bahrad A. Sokhansanj, an independent researcher. They found that the viral subtypes circulating in New York most likely arrived from Europe, whereas West Coast infections originated from Asia but were subsequently caused by a newer subtype that exists only in America.

This work is valuable because separate subtypes may respond differently to therapies or require unique containment measures. It could also possibly reveal mutation-resistant code that can be exploited by a vaccine.

The team made their genetic analysis tool available for COVID-19 researchers on GitHub. — Britt Faulstick

19. Michele Marcolongo et al.

In early March, Professor Michele Marcolongo, head of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in the College of Engineering, received an urgent call from the chair of Einstein Hospital’s emergency room about their critical shortage of face shields.

Could she help?

Within six days, Marcolongo had teamed up with Associate Professor Amy Throckmorton, Professor Ellen Bass, and graduate student Bryan Ferrick to develop a 3D-printed headband with a clear shield and foam padding. Within a month, with the help of additional Drexel researchers, 12 supply donors, and over 20 printers, the team assembled almost 2,500 “AJFlex Face Shields” for local health care workers.

“Our efforts can play a critical role in stopping the spread of COVID-19 in a way that directly helps protect the people most vital to curbing its impact,” Marcolongo noted. “It’s been a wonderful show of community among our engineers and it’s gratifying to know we are making a difference.” — Alissa Falcone