ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN S. DYKES

Walk on any street in Philadelphia, and you’re walking on layers of history — and pipes. Lots and lots of pipes.

“There are literally hundreds of thousands of pipes that are underwater service lines buried in older cities,” says Kurt Sjoblom, formerly in the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering. “Utility companies have no idea whether they’re lead, steel or copper.”

And while utility companies are required to remove any pipes they uncover that are made of lead, there’s no other way to know they’re there.

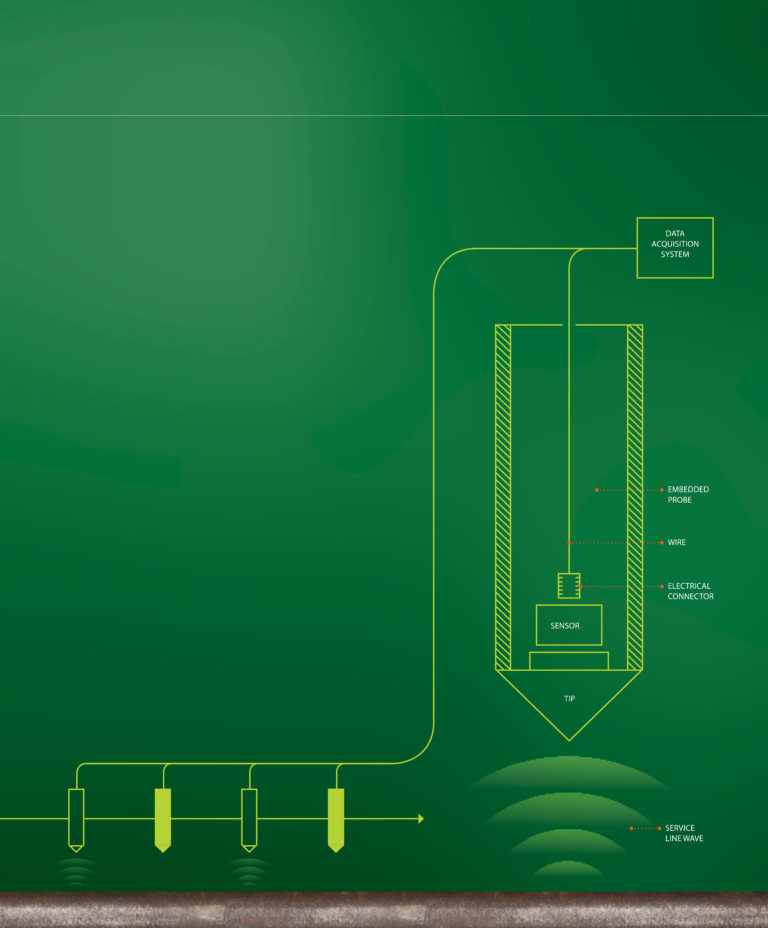

Drexel’s patent covers a device capable of identifying the metal that pipes are made from, without digging them up. The device works by listening to the sound of a small hammer tapping along the ground where a water line leads from the curb to the water main.

“Based on time of travel and known distance, we then calculate the approximate speed of the wave traveling through the pipe,” Sjoblom says. “If that speed is traveling within a certain range, the pipe is most likely to be made of X type of material.”

After the Flint water crisis in 2015, department head Chuck Haas challenged engineering faculty to come up with solutions. Sjoblom had already been toying with using sound waves to identify buried infrastructure, but he wasn’t even thinking of lead pipes.

So far, the device has been tested on water lines in New Jersey, and the researchers are working on the best configuration of, and how many, listening devices a setup should have. They hope to either build a prototype for commercialization or to license the concept to an existing company.

Chuck Haas, co-inventor