WHEN SHAH RUKH KHAN walked onto the stage of a new primetime show in January 2018, the audience was primed for action: The film actor and producer known as the King of Bollywood is the most famous celebrity in India. All eyes were on him as he stood on the vividly lit set of “Ted Talks India Nayi Soch,” a TED Talk series produced in Mumbai for India’s largest TV network.

On that night, though, Khan wasn’t the star. He was there to present Mihir Shah, 40, a youthful-looking, unassuming guy in round glasses. Shah is the Indian-born, Drexel-educated CEO of Philadelphia-based UE LifeSciences, a company that recently debuted a breast cancer detection device unlike anything else on the market.

“Cancer is not a death sentence,” Shah began, speaking in rapid Hindi.

As cameras panned across of the faces of women in the audience, Shah explained that their chances of surviving breast cancer is roughly half that of women living in the United States or Europe, where early detection is more routine. Traditional mammograms are high-tech machines that depend on trained radiologists, he explained; but India has 10 times fewer radiologists than the United States, and they serve four times as many people.

Then Shah showed the audience a 2-inch-square wafer that he promised will even their odds of survival.

The wafer is a unique sensor invented by professors at Drexel, commercialized through the University’s venture infrastructure by Shah when he was a young graduate of Drexel’s computer engineering program, and developed into a one-of-kind, life-saving medical device by Shah’s company. It’s called the iBreastExam, and it is the developing world’s most promising tool for affordable, radiation-free, portable breast cancer screening.

When Shah displayed the device, he spoke not only to the couple hundred people in the studio audience, but to every woman in the developing world who lives far from a hospital, who can’t afford a physician, or who fears radiation.

He finished speaking amid rounds of applause and received a standing ovation. For four minutes and 13 seconds in January 2018 — and to the tens of thousands who have already been screened by his device around the world — this Drexel alum was a superstar.

SMALL, SIMPLE, INEXPENSIVE AND SAFE

The iBreastExam is no heavier than a paperback book, is so simple it operates with just an on/off switch, and is capable of producing individual scans for pennies on the dollar. Unlike hospital mammograms, it is painless and uses no radiation. Yet it is as effective as a mammogram at detecting abnormal breast lumps.

Its size, affordability and simplicity make it uniquely suited to reach women in the developing world where poverty, resources or taboos about radiation deter women from getting basic medical attention — with profound health consequences. In the United States, successful early detection drives breast cancer survival rates of 90 percent, but that rate falls to just 50 percent in countries like India, according to the World Health Organization.

The iBreastExam has been deployed in India, Mexico, Myanmar and Botswana so far and will soon be available in at least eight other countries in Southeast Asia and Africa. It has been used to screen more than 175,000 women and successfully identified more than 120 cases of breast cancer. UE LifeSciences recently inked a global distribution deal with GE Healthcare, the world’s largest purveyor of women’s health imaging products, to expand the device’s reach.

Though the device has been on the market for just two years, the story of how it went from a professor’s lab bench to clinics and community health fairs around the world is tied to Shah’s personal story, and goes back nearly 20 years to when he came to Drexel as a student.

Shah grew up in Mumbai, a city famous for its movies and density. Home life was stable — dad would call every day to make sure he’d gotten home from school — but things were not easy, certainly not by American standards.

“We had all the basic necessities and things seem to last forever,” Shah says of his childhood. “We had one television that we used for 10 years! Dad always had a car, nothing fancy though. He’s very modest, Old Spice is the only cologne he’s ever used. Other kids had the latest toys and I got them maybe a season or two later.”

The iBreastExam is based on research that Shah licensed from Drexel researchers Associate Professor Wan Shih and her husband, Professor Wei-Heng Shih, who found a way to use electric currents to identify abnormal lumps within tissue. The technology is unique because it can detect tiny early tumors, even in dense breasts, making it perfect for early detection.

His first English word, “load shedding,” speaks volumes about growing up in India. Load shedding is when the power goes down because too many households are drawing on the grid. “We would lose lights all the time and I heard my parents talk about it,” he recalls. “My dad would work 12 hours a day and when the power was out he would come home and manually fan me so I could go to sleep.”

It took a Drexel scholarship, all the family’s savings and some high-interest loans to bring Shah to the United States at age 18 in 1996.

When he entered Drexel as a freshman, he spoke only adequate English: It’s his third language, after Gujarati and Hindi. He came seeking a computer engineering degree, even though he’d only ever used a laptop twice. A self-described “straight B+” student, he didn’t seem cut out for academic stardom. But his family had scrappy business instincts: His dad was a “trader,” which in India meant he cobbled together a upper-middle-class living buying and selling used textile manufacturing equipment.

Shah got his first formal insights into business when he took a class in basic entrepreneurship from Robert Loring ’84, a Drexel alumnus who founded a multi-million-dollar health care services company before returning to Drexel to teach and assist faculty and students with tech transfer. (Today, Shah is teaching that same class himself as an adjunct.)

“It appealed to me at the core because I had seen my dad and my family do this, even if it had been in a very unorganized way,” he says, describing how his dad and family members would strike ad hoc deals with textile manufacturers, buying and selling used equipment on the fly, without a set plan but always with a little profit at the end. “They were winging it. My dad has never signed a single contract in his business life, and yet he’s never had a single legal issue. He showed me what matters. Conversations matter. When you promise something verbally, you take that very seriously. Dr. Loring’s entrepreneurship class opened my eyes to what I had been seeing all those years.”

The class inspired him to the attend a networking event for students interested in entrepreneurship, where he was pulled into a project writing real estate appraisal software for Drexel alumnus Mark Silverman ’86. A few years later, Silverman helped Shah compete in Drexel’s business plan competition. Shah and his partner Nilay Jani won the contest and earned $5,000 and office space in Drexel’s new student startup incubator, the Baiada Institute for Entrepreneurship, run by the Close School of Entrepreneurship — becoming the incubator’s first tenants in 2002.

The iBreastExam is portable, painless, radiation-free, and as effective as a mammogram at detecting abnormal breast lumps. It costs just $2 to administer an individual scan, versus mammography fees that typically range from $6 to $30 per screening. It is sold as a kit in a leather case that includes the handheld breast scanner and a smartphone that runs an app for quickly analyzing test results and storing results in the cloud.

Being in Baiada put them alongside staff from Drexel’s Office of Technology Commercialization, some of whom have remained mentors to this day. “We’d share lunches and learn what tech transfer is,” Shah recalls. “I was amazed: Are you telling me that the best discoveries and inventions made at the University could be commercialized by someone like me? I’m thinking, ‘That’s what I want to do.’”

He spent some time in the following years exploring technology trends, but he was searching for something bigger. He gradually became more embedded in Drexel’s venture ecosystem, getting to know the players in tech commercialization. One was Banu Onaral, who served as the founding director of Drexel’s School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems and who spearheaded the Coulter-Drexel Translational Research Partnership Program — a major Drexel conduit for bringing faculty inventions to market.

Onaral, who is now a senior presidential adviser for global innovation partnerships at Drexel focused on emerging economies, says she championed Shah because she could see that he had his heart and mind set on making a difference in the lives of the underserved and unprivileged.

“He had what it took to effect change in health care,” she recalls thinking. “He just needed to be tested on the ground.”

In 2004, Onaral invited Shah to take a prototype of a non-invasive cardiac monitoring device to India for clinical evaluation. “They wanted real-life data, and I wanted people in India to benefit from this medical innovation,” Shah says.

The catch: he would have to come up with $25,000 to “buy” the prototype that he took with him. Shah, then 26, pulled together his earnings from his earlier real estate software venture and

booked a working vacation.

“I called seven or eight top-notch cardiologists in Mumbai, introducing myself as an entrepreneur from the United States and describing this medical invention,” he recalls. “I showed them the brochure and suggested we work together as ‘clinical collaborators;’ all I really needed was these key opinion leaders to try it out.”

The next thing he knew, he was in the operating theater getting scrubbed.

“I saw a live birth take place. I saw open heart surgery. All these people were benefitting from the cardiologist and the anesthesiologist constantly looking at this machine,” recalls Shah. “When I saw real life patients benefitting from this medical innovation, I was hooked. I decided to drop everything I was doing and pursue medical technology development and commercialization.”

He returned to Drexel with 60 case studies, enough data for Drexel’s tech transfer office to get the device licensed to a U.S.-based med-tech company. He’d found his niche.

And then, in late 2006, his soon-to-be mother-inlaw in India was diagnosed with breast cancer.

THE PATH TO DISCOVERY

His wedding was just six months away when Shah’s mother-in-law learned that her cancer was already at stage 2. It was invasive, and had moved into her lymph nodes. She underwent surgery, then six months of chemotherapy. At the wedding, she wore a wig.

Over the following years, Shah learned of eight other women among his friends and family who were diagnosed with breast cancer. Four didn’t make it. “India’s national average is similar: for every two women diagnosed, one doesn’t survive,” Shah says.

“You cannot escape it when breast cancer happens so close to your home,” he says. He began educating himself about the disease: Where does it come from? How is it detected?

“I started learning there was this huge disparity of outcomes for women in the developed world versus the developing world. In the United States, my mother-in-law’s case would have had an 90 percent survival rate, but in India it was 50, a coin flip,” he says.

Why the disparity? Early detection is a big reason. In India, like many developing countries, women can’t always travel to a faraway clinic for a screening. Cultural taboos may discourage exposure to radiation. Mammography is expensive and harder to access.

As Shah learned more, he found that early detection is also stymied by breast density. When the tissues of the breast are densely wound, radiation from the mammogram cannot penetrate them — and tumors go unseen.

Naturally dense breasts are common among young women, women of certain ethnicities such as Asians, and about 40 percent of women over 40. The sensitivity of a mammography machine, which can be as high as 80 to 98 percent, drops to between 30 and 64 percent in women with very dense breasts, according to the Radiological Society of North America.

As chance would have it, faculty researchers at Drexel were experimenting with technology that could address just this problem.

In the School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems, Associate Professor Wan Shih had been studying a phenomenon called “piezoelectrical effect” for a couple of decades. Piezoelectrical effect refers to the ability of certain materials to generate an electrical charge when pressure is applied.

WHEN I SAW REAL LIFE PATIENTS BENEFITTING FROM THIS MEDICAL INNOVATION, I WAS HOOKED.

In collaboration with her husband Wei-Heng Shih, a professor of materials science and engineering in Drexel’s College of Engineering; PhD candidate Hakki Yegingil; and surgeon Ari Brooks, MD, director of the Integrated Breast Center at the Pennsylvania Hospital, Shih investigated how piezoelectrical ceramic materials, when compressed by an electric current, could be used to map adjacent substances. Their innovation was to find a way to manipulate the ceramic material — a finger-like tool that is flexible like a diving board — in such a way that it could be used to detect the slightly harder form of a tumor within surrounding tissues.

The technology can detect tiny early tumors, even in dense breasts, making it perfect for early detection in all women — young, old and across all ethnicities.

“That’s something entirely new,” she says. “Without this, the only way to quantify tissue stiffness is after the tissue is cut out from the human body. Now you have an instrument that you can use to measure the stiffness of tissue on a living human being.”

Shih and her co-researchers obtained a patent for a “soft material stiffness” sensor in 2009 — one year after being herself diagnosed with aggressive ductal carcinoma of the breast and undergoing treatment.

By this time, Shah was serving as a Drexel entrepreneur-in-residence and had begun working — with his UE LifeSciences co-founder Matt Campisi (an introduction made by Banu Onaral) — on a different non-invasive breast cancer detection tool that used thermal imaging to spot telltale concentrations of heat that indicate a tumor.

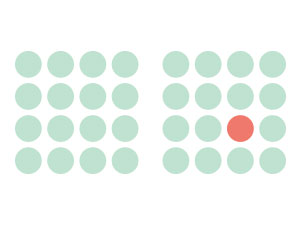

In the United States, early detection of breast cancer has helped national breast cancer survival rates achieve 90 percent. But that rate is just 50 percent in India, which has 10 times fewer radiologists than the United States, and four times as many people.

Shah thought that that tool, called the NoTouch BreastScan, would be cleared by the FDA in a few months. Instead, the FDA lingered over it for two and a half years while the agency fretted that it would confuse consumers and deter them from getting mammograms. Then, the FDA said no.

“That was the darkest hour,” Shah remembers. “I had no Plan B.” He and Campisi had started the company with a $150,000 friends and family fund — practically nothing for a med-tech startup. For three years their head of operations and de-facto co-founder, Bhaumik Sanghvi, went without a salary. A year and a half into it, Campisi was offered a six-figure salary by another company. Campisi turned it down, saying he believed in Shah and the mission. No pressure!

“There’s a resilience and team bonding that only failure can make happen,” Shah says of the experience. “Now when something doesn’t go the way we expect, we don’t get stressed out.”

They wrote a letter to the FDA explaining the situation and incredibly, that worked. The FDA cleared NoTouch BreastScan in February 2012.

But by then Shah had been introduced to Wan Shih and her piezoelectrical sensor technology through his involvement with Drexel’s Coulter-Drexel Translational Research Partnership Program — a major Drexel conduit for bringing faculty inventions to market. He immediately saw the technology could reach women in their community better than the more cumbersome and costly NoTouch BreastScan.

Major med-tech companies were interested, too. Shah went to the Shihs and to Alexey Melishchuk, the associate director of licensing in Drexel’s Office of Technology Commercialization which managed the University’s intellectual property, and he promised, “This technology would be one among many for those large companies, but I’ll make it my life’s work.”

He got the license.

THE ROAD TO MARKET

Still, UE LifeSciences needed funds.

“We had licensed the technology from Drexel in late 2010 but had no money to further develop it,” Shah recalls. “Our first machine [the NoTouch BreastScan] wasn’t yet FDA cleared so we had all these bills to pay and our first working product was still in limbo.”

An assist from Drexel saved the day. A mentor in the Office of Technology Commercialization, Senior Associate Vice Provost and Executive Director of Technology Commercialization Bob McGrath, tipped Shah off to a Pennsylvania Department of Health call for grant proposals, and as luck would have it, the state wanted to fund specifically the development of tools for cancer detection and treatment.

“That Pennsylvania grant was akin to the one shot that Luke Skywalker had in ‘Star Wars’ to destroy the Death Star — that one chance in a million to hit the target,” recalls Shah.

Despite never having written a grant proposal before, Shah went head to head against accomplished PhDs to compete for the grant money, and he vividly recalls the phone call in February 2012 telling him he had won.

“That’s when life changed,” Shah recalled. “It took me a while just to adjust my mindset. I thought it must be one of my friends playing a prank. But I opened my email and there it was in official words.”

Later, at a formal ceremony handing over the $878,000 grant, the state Secretary of Health took Shah aside. “He told me, this is your golden ticket. Spend this money as if it’s your own. We are trusting that you will build a product that will save lives,” Shah remembers.

Shah and Campisi put together a team of 27 clinicians, researchers, engineers and coders in the United States and India and began building.

Shah knew that to succeed commercially, the device would have to be portable enough to serve remote villages. It would have to be simple enough for any community health worker to use it without a doctor or radiologist. It had to connect wirelessly to the internet and use small data files. It had to be rugged in humid and hot environments. It had to be impervious to breast density.

All that, and it also had to be “ridiculously affordable,” Shah says.

In two and a half years, they had the iBreastExam. With FDA clearance in hand, and approval for medical use in Europe, his company now employs over 70 people in the United States, India and Malaysia. Two key numbers help to explain the adoption of the new screening test: 85 and 92.

“It has been through four clinical studies and has shown over 85 percent sensitivity and over 92 percent specificity,” Shah says. “Both of those are measures for the detection of breast lumps and lesions. Sensitivity means you can detect a lump when it is there, you don’t miss it. Specificity means you can tell when it is not there: It means you have fewer false alarms.”

Mihir Shah received a standing ovation from a primetime audience last year in Mumbai when he spoke about the iBreastExam on India’s televised version of the Ted Talk.

Another key figure: $2. That’s how much it costs to administer an individual scan with the device, versus mammography fees that typically range from $6 to $30 per screening.

In line with these findings, the World Health Organization included iBreastExam in its latest compendium of innovative health technologies for low-resource settings, noting that in India alone, which is home to over 190 million women age 30–65, approximately 35 percent of the female population may benefit from access to early detection.

Things are picking up speed now for UE LifeSciences. A big piece of the commercial puzzle fell into place in summer 2016, when Shah was invited by Terri Bresenham, chief innovation officer at GE Healthcare and the head of its Sustainable Healthcare Solutions effort, to give a demonstration of iBreastExam’s technology. GE Healthcare had been scouting startups for emerging technologies to help serve people in developing countries.

Shah presented to a room packed with about 80 executives, including the heads of its mammography, utrasound and MRI divisions. Diplomatically, he described ways that their mechanisms fell short in some parts of the world, and how iBreastExam — handheld, mobile, easy — was filling in the gaps.

“And I kind of see Terri sit more upright in her chair,” recalls Shah. “I had her right in front of me, with the head of the ultrasound business sitting next to her. I could physically, visibly see their expressions change. She started looking behind at her colleagues, like, ‘Are you seeing this?’ And she had a little smile on her face.”

Bresenham was thinking it was one of the best ideas she’d heard in a long time. In November 2017, GE Healthcare inked a deal to distribute iBreastExam in more than 25 countries in Southeast Asia, South Asia and Africa as an adjunctive tool in its health care portfolio — expanding screenings to more than 500 million women in developing countries.

‘MISSION DRIVEN’

At the Close School of Entrepreneurship, Dean Donna De Carolis has watched Shah bring his company to life.

She says that on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the hardest, bringing medical technology to market is a 7.

“He’s been determined to make this a success, come hell or high water,” she says. “He also has a very engaging personality, he’s a great storyteller, and that is something entrepreneurs need to get people to buy into your vision.”

Shah achieved that buy-in by telling a story that struck precisely at the intersection of high-minded idealism and commercial potential, says Kathie Jordan, director of the Coulter-Drexel Translational Research Partnership Program.

“What we are doing [at Drexel] always has a greater purpose, to serve humanity in general,” Jordan says. “Then we add this other piece by thinking about the commercial pathways as a means to turn those dreams into a reality.”

He’s been determined to make this a success, come hell or high water.”

Within the University, a network of programs, mentors and funding and top-notch ideas exist to get entrepreneurs started, says McGrath in the Office of Technology Commercialization. In addition to the Technology Commercialization office, Shah had access to the then-new Baiada Institute incubator; Drexel’s School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems; and to a range of entrepreneurship expertise. “He has been plugged into a very supportive community,” says McGrath.

The opportunity to impact health on a global scale would never have materialized without the support mechanisms at Drexel, Shah agrees.

“To develop an idea like this means you need clinical validation, regulatory approvals. You need funding to sustain the venture and commercialize it. You have to have partners to give you ground strength,” he says. “It’s a challenge that can only be overcome by an entire ecosystem.”

Over the years, Shah’s parents have watched his progress with pride and joy.

“Many years ago, when I decided to send my son to study at Drexel, it was not just to get a good education,” Shah’s father Bakulesh recalls. “I truly wished for him to bring something of much greater value back to India and help people in a unique way. I believe Mihir has far exceeded those expectations. He has all our love and blessings, every step of the way.”