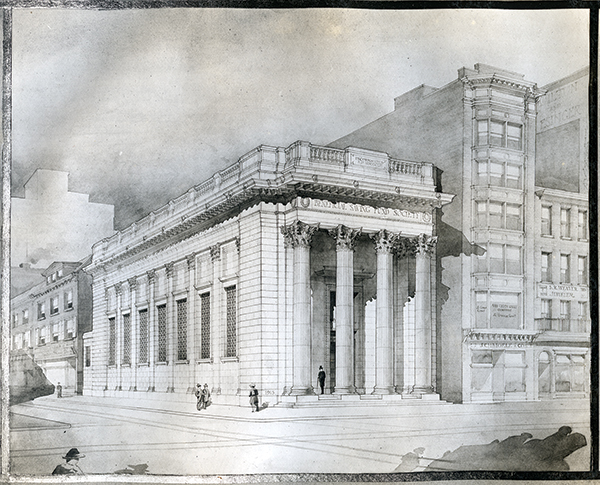

With long, determined strides, attorney Tom Kline walks past the granite-columned entrance and into the marble lobby of 1200 Chestnut Street, a 1916 Horace Trumbauer gem freshly buffed to a beautiful shine after four years of renovation under the hand of architect Jay Tackett. Formerly the banking headquarters of Beneficial Savings Fund Society, it had stood empty for more than a decade until Kline saw in its classical lines the promise of a modern purpose, and purchased it in 2012 to eventually house the new Thomas R. Kline Institute of Trial Advocacy. Today in one of his first tours since it reopened to the public, Kline is displaying it to a reporter, and it is magnificent.

The grand, larger-than-life lobby is a fitting setting for Kline, who is one of the country’s most celebrated and renowned trial lawyers. In his career spanning over four decades, he has become known for obtaining significant jury verdicts and settlements that have positively and dramatically influenced corporate, institutional and government behavior. This reconstructed building, like Kline’s life’s legal work, represents positive and meaningful change.

“The Beneficial renovation is both a shrine to one of democracy’s bedrock values, trial by jury — and to Kline’s career,” wrote Inga Saffron, The Philadelphia Inquirer’s architecture critic, in a glowing review of the building in June. “Solid, neoclassical banks like Trumbauer’s are often seen as architectural expressions of America’s democratic values. In its new life as a law school, the renovated bank has become more than a symbol of those beliefs. It now plays a role in defending them.”

The institute’s location — just blocks from City Hall and state and federal court buildings — provides students of Drexel’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law easy access to the Philadelphia legal community and makes it the only regional law school to have a Center City presence. The building dominates the cityscape in a neighborhood undergoing a transformation and resurgence.

For Kline, the new Institute of Trial Advocacy building is both an immersive legal classroom and a symbol of the approach to the practice of law embraced by Kline School of Law students and faculty. “The building has an inspirational and aspirational aspect to it,” says Kline. “It is designed to convey the role of the advocate in achieving a remedy that results in accountability and leads to reform.”

Drexel’s newest and most elegant academic building is a law school edifice unlike any other, thanks to Kline, who gave the building to Drexel in 2014 as part of a record $50 million gift. The dramatic lobby where tellers once stamped deposit slips is now a grand reading room spanned by an intricately embossed 50-foot artisans’ plaster ceiling, which has been restored to its original perfection under the auspices of the National Park Service and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

1200 Chestnut Street was built in 1916 by famed architect Horace Trumbauer to house the Beneficial Savings Fund Society. For many years the bank operated it as an opulent vault for the savings for the city’s rising immigrant labor force. But by the 1970s the property was losing its luster alongside midtown’s falling fortunes, and Beneficial finally vacated it in 2001. Kline purchased it in 2012 and gave it to Drexel in 2014.

A staircase leads to a glass-enclosed grand courtroom overlooking the reading room that is punctuated by a 12-foot video screen and a state-of-the-art audio system surrounded by marble walls. The building houses faculty and administrative offices, and four additional courtrooms/classrooms where on any given day one can find student advocates on their feet, examining witnesses and preparing opening and closing statements. The bank’s original stately wood-paneled boardroom with a working fireplace is now meticulously restored and illuminated with pendant fixtures rescued from the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, and still boasts chairs that bear the sterling silver nameplates of its mostly Irish bank directors from an earlier time.

Even the custom-made carpet underfoot has a lesson to impart. Woven into its design is a passage from the Pennsylvania Constitution: “Trial by jury shall be as heretofore and the right thereof remain inviolate.”

Outside, thick neoclassical 40-foot columns line the side of the building facing 12th Street. The entrance on Chestnut Street is flanked by two additional columns and imposing bronze entry doors, meticulously restored. “The procession up the short flight of steps into the soaring banking hall makes you feel like royalty,” Saffron wrote.

Even before the institute opened, the Kline School of Law was on its way to securing a reputation for grooming the nation’s best student trial advocates. Kline students won the prestigious Tournament of Champions in both 2016 and 2017, which is sponsored by the National Board of Trial Advocates. The Kline School of Law holds the title of having the first all-female team to win the American Association for Justice Student Trial Advocacy Competition in 2016. A Kline graduate won the Top Gun National Mock Trial Competition in 2018. Most recently, the school was ranked 4th in the nation in the Trial Competition Performance Rankings published by the Fordham University School of Law.

The trial advocacy curriculum is now being taught in this grand setting. Daily courses range from introductory and advanced trial advocacy to the taking of depositions, along with trial team training and practice.

“The building is set up to make us the best training facility for trial advocates in the country,” says Kline School of Law Dean Daniel M. Filler.

The institute will take the law school “to another stratosphere,” vows Gwen Roseman Stern, director of the Trial Advocacy Program. “No other law school in the country has a facility like this. Tom is a pillar of an attorney, standing up for victims and justice, and the building will enable students to be trained to follow in his footsteps.”

“The building stands as a monument to advocacy,” Kline says. “As I have said many times to students at graduation, there will never be an oversupply of advocates and there will never be an undersupply of worthy causes.”

Visitors who pass between the building’s ionic columns and marble threshold today enter an ornate lobby where the trappings of its Gilded Age origins survive as a spectacular setting for a new, more progressive mission.

Kline grew up in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, a small town that once thrived on anthracite coal mining. After graduating from Albright College in nearby Reading, he spent six years teaching middle school social studies. During that time, Kline received a master’s in American history from Lehigh University and completed the coursework for a PhD before going on to attend and graduate from Duquesne University School of Law. In July 2017, Kline donated $7.5 million to establish the Thomas R. Kline Center for Judicial Education of Duquesne University School of Law, which will provide ongoing legal education for state judges.

He clerked for the late Pennsylvania Supreme Court Justice Thomas W. Pomeroy Jr. before entering private practice. In January 1980, Kline moved to Philadelphia and worked alongside famed trial attorney James E. Beasley, after whom Temple’s law school is named. Kline often remarks that he was trained at the “real” Beasley law school.

Kline worked at the Stephen Girard Building and the Beasley Building, both within a stone’s throw of the Beneficial building, which he came to admire.

In 1995, Kline and Shanin Specter, a nationally prominent trial lawyer and distinguished law professor, left Beasley to establish the law firm of Kline & Specter, where he became known for his skillful examination of witnesses and moving opening and closing statements. Success followed success, and their firm now has more than 40 lawyers, including seven graduates of the Kline School of Law, and is considered among the most elite and influential of plaintiffs’ personal injury law firms in the country.

The original boardroom created for Beneficial Saving Fund Society has been preserved as a conference room, complete with original wood paneling, working fireplace and chairs that still bear the sterling silver nameplates of the bank’s board of directors.

Kline has been named the No. 1 attorney in Pennsylvania for 15 years running by Super Lawyers, an independent peer review rating organization, and is the only lawyer in the United States to hold such a distinction. Kline was recently named one of the nation’s “100 Influencers in the Law” by The Business Journals. In 2016 he received the Michael A. Musmanno Award, the highest honor conferred by the Philadelphia Trial Lawyers Association to the person who best exemplifies “the same high integrity, scholarship, imagination, courage and concern for human rights” as did the late Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice. He also recently received the Lifetime Achievement Award by The Legal Intelligencer.

In addition to its numerous remarkable educational spaces, the institute building will house a motivational and educational exhibit hall created in a collaboration between Kline, designer Kim Tackett, and Rosalind Remer, Drexel’s vice provost and executive director of the Lenfest Center for Cultural Partnerships.

It is based upon the bedrocks of Kline’s legal career, which is capsuled in four fundamental concepts: advocacy, remedy, accountability and reform. On both the first and fifth floors of the building, the exhibit weaves together the core components of Kline’s career as an inspiration for aspiring attorneys.

On a second-floor landing overlooking the lobby is a glass-enclosed grand courtroom equipped with a 12-foot video screen and state-of-the-art audio system, to be used by legal students as space to practice courtroom arguments.

The first of the four pillars of which the building and Kline’s career have been built is advocacy. The exhibit focuses on Kline’s advocacy in the courtroom and beyond the courtroom, the latter of which Kline describes as “the court of public opinion.” Kline became the most prominent national spokesperson for victims of child abuse in his representation of a man known as “Victim 5” during the infamous sex abuse scandal involving Penn State University’s former football coach Jerry Sandusky. More recently, Kline has represented the parents of fraternity hazing victim Timothy Piazza, and has become a tireless advocate for new state legislation that sets the nation’s toughest penalties for hazing. In both endeavors, he has appeared in national news broadcasts and in every major newspaper across the country.

Kline’s second pillar is remedy, something he has achieved for hundreds of clients for over 40 years. At the institute, he has chosen to display one letter of gratitude from one client, Linda McCalister, whose catastrophically injured child benefitted from Kline’s skillful representation. That letter has the impact Kline hopes will motivate the advocates of the next generation.

Philadelphia advocate Thomas Kline.

Kline’s third pillar is accountability, demonstrated throughout his career, and exemplified in the exhibit by his relentless pursuit of justice on behalf of victims of defective drugs and devices. He has successfully obtained jury verdicts against pharmaceutical and device companies involving many products in each of the four decades in which he has practiced law. Among many other examples, he played a key role in the national litigation against Merck & Co.’s Vioxx pain medication.

The final pillar is reform, and here Kline has presided over many cases that have led to lasting changes. One example is a case involving the Philadelphia police shooting of Phil Holland, an innocent victim, which resulted in a new training protocol for plainclothes police officers. It made the streets safer for the citizens of Philadelphia and those who police the city’s streets, and provided a national model.

A reminder of one of Kline’s most famous cases resides in a unique space on the fifth floor of the institute. Under a section of the floor, set behind glass, Kline and Tackett installed parts of an old escalator from a salvage yard to recreate Hall v. SEPTA, which involved a 5-year-old boy who lost his foot in an escalator accident. Kline held SEPTA accountable, ultimately forcing the transit agency to remediate and repair its entire subway escalator system. From that case arose a phrase that Kline has often repeated: “Something good can come out of something bad.”

As part of the building’s restoration, Philadelphia architect Jay Tackett revived the building’s original embossed plaster ceiling that soars 50 feet over the lobby and reading room.

The SEPTA case was followed later by Kline’s advocacy in representing families of those who lost loved ones in the Pier 34 collapse in 2000 and in the Amtrak 188 derailment in 2015, both of which cases are also memorialized in the main exhibit hall.

These examples of a long and meaningful career provide a path for future generations of Kline School of Law students to follow. Beginning with students’ first steps inside this grand edifice to the moment they walk for commencement, they will be standing on a solid academic foundation grounded in principles, purpose and the impact of a distinguished, accomplished and engaged faculty. The new institute building, as Kline sees it, is a cornerstone upon which faculty and students can build a prominent future in American legal education.