Thomas Sharpe was up early one morning in 2014, finishing a class assignment in the URBN Center, the building that houses the Westphal College of Media Arts & Design. Dawn was breaking and the vaulted, industrial space was hushed and empty. As he watched the sun ricochet off the glassy Philadelphia skyline, a vision struck him.

What if he were to awake one day and find the sun had inexplicably failed to chart its usual course? What if everything stayed masked in darkness?

Sharpe, who graduated from Westphal in 2016 with a bachelor’s in game art and production, grew up in Bandera, Texas, a middle-of-nowhere town an hour outside San Antonio that styles itself as the “Cowboy Capital of the World.” Most of the local entertainment came on horseback. But while the rodeo rumbled, Sharpe was home playing video games, making his way through an ever-expanding universe of digital adventures.

That morning, watching day break in University City, an idea for an unusual video game stirred in Sharpe, and he embarked on his biggest journey yet.

Soon after, he joined the Entrepreneurial Game Studio, an incubator for student-run video game startups within Westphal. Sharpe assembled a team of fellow student programmers and artists to join his studio, Gossamer Games. Over the next two years, an evolving team built on his vision, creating a single-player game that explores the quality of loneliness in a world gone dark.

Brilliant Vision: Thomas Sharpe formed Gossamer Games with Nina DeLucia and Vincent De Tommaso.

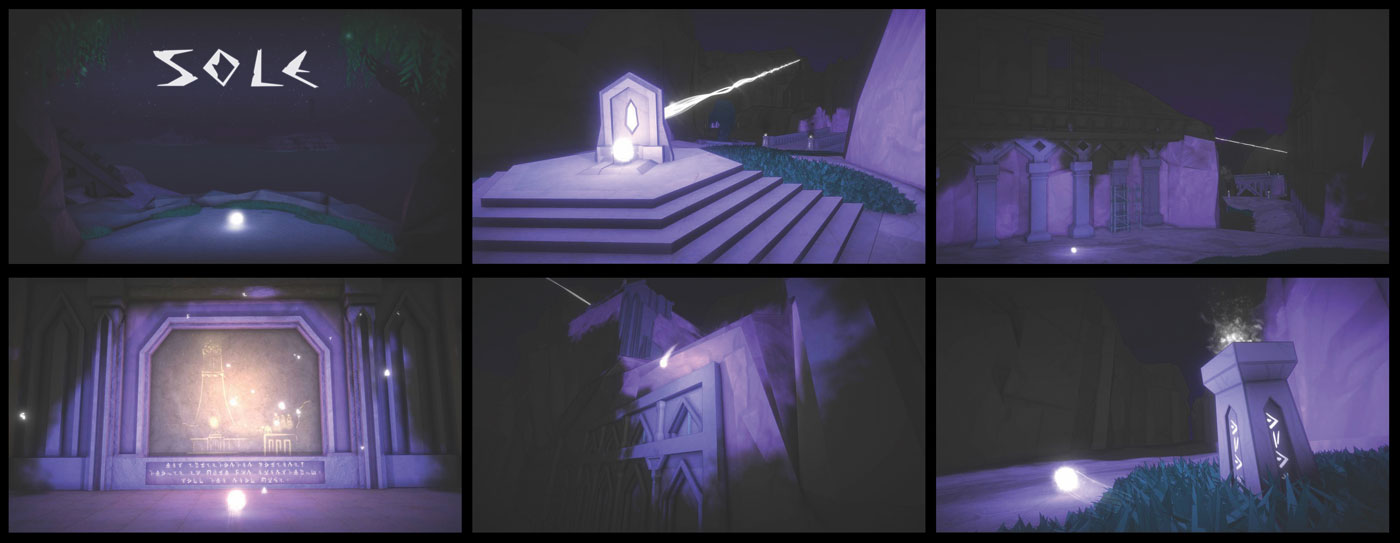

In “Sole,” a player travels alone as a tiny ball of light through a somber, quiet city where it is the only source of illumination, revealing the world as it goes. In an industry brimming with brash first-person shooters and candy-colored, mindless mobile games, “Sole” stands out as meditative, introspective and, most rare of all, emotionally resonant.

When “Sole” is released later this year, it will be the 10th game to emerge from the Entrepreneurial Game Studio since its inception five years ago. And judging from the landscapes Sharpe and his team have already completed, it will be the program’s most artistically ambitious game yet.

Inside the Gamer’s Studio

The Entrepreneurial Game Studio is a tiny hub tucked inside Drexel’s Expressive and Creative Interactive Technologies (ExCITe) Center, a suite of labs and classrooms where on any given day students may be weaving functional fabrics, building out a virtual reality experience or tinkering with robotic technology. The studio’s unofficial signpost is a Super Mario Bros. illustration, familiar green tubes and all, that runs the length of the center’s back wall. A few paces down the hall, the studio itself occupies a small room filled with computer equipment and, most days, at least a handful of busy programmers designing three-dimensional chairs or trees or kittens hurtling through outer space (for whatever reason, at least two teams of students have developed games that feature felines in the cosmos). A painting of a Pac-Man chomps across the back wall.

The Entrepreneurial Game Studio was founded in 2013 by Frank Lee, a professor of digital media in Westphal, with funding from Drexel and Pennsylvania’s Department of Community and Economic Development. Lee is perhaps best known locally for programming the exterior lights of the 29-story-high Cira Centre to play a massive game of Pong in 2013 and Tetris in 2014.

His inspiration for the studio was, partly, desperation. In 2008, when he helped establish the Game Design undergraduate program at Drexel, there was no local commercial gaming industry that his students could turn to for co-ops and jobs. For years, he watched students graduate from his program and disappear to other cities. He tried to convince some big names in the industry to set up shop in the city, and even worked to get the state legislature to pass a bill that would support them with tax credits and the like, but it all fell through. So, in the Drexel spirit, he struck out on his own to fill the void.

“I felt like it was completely out of my control,” Lee says. “But what I could do was create a factory for video game startups and hope one of them hits it big.”

He dreams that one of his student-run companies will find success and lay roots in the neighborhood. All it takes is one company, he says. In Gossamer, he hopes to have that seed.

In a typical year, there are 40-plus students involved with the Entrepreneurial Game Studio, split into teams of four or five members and tasked wit creating a company — not just a student project, but an actual functioning LLC. Their objective is to publish a commercial game by the end of the year.

Lee wants his students to cope with the real-world issues they’ll encounter beyond Drexel — starting a company, pitching ideas to colleagues and investors, showcasing progress, developing a popular product. Sharpe and his Gossamer team went to conferences and entered competitions, showing off their work and developing skills along the way in business and marketing that he says he lacked when he joined the program. They did it all with Lee’s support, knowing that they were in a safe space designed to encourage and support their growth.

“In order to be a successful entrepreneur, you have to make a ton of mistakes,” Lee says. “I want students to make all those mistakes with me, while they’re at Drexel, so they can succeed once they leave.”

Play Station: The Entrepreneurial Game Studio is a members-only incubator for gaming teams intent on creating startups.

Studio membership is an act of dedication. Students must apply to join but receive no course credit for their participation. If they miss a meeting they’re placed on leave. They even fix their class schedules around the mandatory Wednesday afternoon project update meetings. The expectations result in a passionate collective of game designers.

The mood in the small studio space is typically jovial, even playful. There are regulars, just like at a neighborhood coffeehouse. Arianna Gass, the studio’s former program manager, used to work in there with all the students until it got too loud to concentrate and she relocated. Spending so much time among like-minded, games-crazed designers and programmers has created a tight-knit, supportive group, she says.

“I’ve had former students at Drexel contact me and say that the community is so important, it was so helpful while they were here and the kinds of conversations they were having with students were way better than the ones they’re having now in the indie community,” Gass says.

For Sharpe and others, the strong community makes the games better. When he has needed it, he can get an assist from a member of another team with an eye for color palettes, or a second opinion on a new idea. Even something as simple as a closer look at marketing copy helps the finished product.

“People are always seeing the game, looking over your shoulder, offering feedback, and I think that has tremendous value,” Sharpe says. “A lot of times when you’re working on a game, you’re in the dark. You don’t see the game how other people see it. So having somebody constantly looking over your shoulder who has fresh eyes…I think that’s very unique in this kind of collaborative co-working space.”

Up to this point, most of the games developed inside the Entrepreneurial Game Studio have been on mobile platforms because their smaller scope and lighter technical requirements make quick production with a small team feasible. The studio’s output includes Lunar Rabbit’s “Starbright,” a two-dimensional, physics-based game that sees a star hurtling through the galaxy, gaining mass as it avoids black holes. Sweet Roll Studio’s “Malevolence Inc.” is a competitive pass-and-play mobile game in which players assume the role of villains working to trap their opponents as they run through disco-themed, platform-style levels. Still others involve navigating a fish through a maze (Aquarius Games’ “Chubby Guppy”) or breaking blocks under pressure, like a spin on “Tetris” (Fox and the Little Prince’s “Alchemia”).

Last year, the studio hit a milestone when one of its student startups released a computer game — Sweet Roll’s “Fantasy Fairways” — on Steam, the digital games storefront available to PC, Mac and Linux users. “Fairways” is a puzzle game of sorts that imagines a round of golf played on a Rube Goldberg- style obstacle course. It is the studio’s furthest foray yet into a video game industry that now brings in more than $100 billion globally each year, according to market analysis firm Newzoo.

The top end of the industry is dominated by blockbuster games — sports franchises like “Madden” and “NBA 2K” and massively popular series like “Call of Duty” and “Grand Theft Auto” — that cost tens of millions to develop and several times that to market, on the way to millions of copies sold. For most indie games, which are typically designed by much smaller teams with lesser funds for release on Steam and the consoles’ downloadable marketplaces, success means selling tens of thousands of copies.

Over the past decade, indies have become more prominent in the gaming conversation as technology has helped lower the barriers to entry for creative minds. The revolution has nurtured a niche of games that take a different direction, toward concepts that draw players in with narrative and aesthetics — less action, more art. The approach is hardly new; one of the earliest computer games, the 1980s adventure game “Zork” (created by two students at MIT, it so happens) was all narrative — literally just lines of text on a screen.

But with Steam and downloadable marketplaces on Sony and Microsoft’s consoles, indie developers have flourished. Games like “Limbo,” a side-scroller about a boy looking for his sister in the afterlife, and “Gone Home,” a first-person adventure about a young woman who returns home from college to a deserted house and an eerie mystery, are attracting — and inspiring — a new audience. It’s that small corner of the gaming world — more brains than brawn, more conceptual than competitive — that Gossamer hopes to edge into.

“Sole” started while Sharpe was a student and has become a post-graduate project with team members Nina DeLucia (animation and visual FX ’16) and Vincent De Tommaso (game art and production ’17), with Nabeel Ansari (junior, applied mathematics and music) providing music and sound. It represents a step toward the abstract.

It has the look, sound and feel of the more inventive indie games populating the indie marketplace — “as much art as game,” Lee says.

The Lonely Orb: In Gossamer Games’ “Sole,” the player travels as a small glowing ball through an uninhabited city where it is the only source of light, illuminating the landscape as it passes.

A few days after graduating last year, Sharpe found out that Gossamer Games had been accepted for a year-long fellowship in the Baiada Institute for Entrepreneurship, a student-startup incubator inside the Close School of Entrepreneurship. With greater funding, space and business resources than those available in the smaller, less-formal Entrepreneurial Game Studio, Sharpe focused on building the world of “Sole.” He had the team to do it.

De Tommaso, Gossamer’s senior environment artist, was fresh off seven years working in finance when he came to Drexel for a second undergraduate degree. He was happy to leave corporate life. “You sit in your cubicle in rows of a thousand and the most creative thing you can do in a day is make an Excel sheet,” he says.

He wanted to get back the feeling he used to have going to the mall with his grandmother to pick through the bin of games — still on floppy disks back then — and plug in a new experience. All of his life he’s been jotting down ideas for games, maybe hundreds in all, and when he learned about the Entrepreneurial Game Studio, he decided it was time to see some of his ideas through.

“You get to invent everything,” De Tommaso says about the lure of making video games. “With ‘Sole,’ we got to invent the history of this planet, the people who lived there, every little thing about them. That’s the most fun. World creation.”

DeLucia, the 3-D texture artist on “Sole,” grew up with role-playing games — richly detailed journeys through expansive environments. “Final Fantasy XII” was the first one she remembers playing, and the one that inspired her.

“It never occurred to me when I was younger that someone had to make these games I was playing, and then I remember I was playing ‘Final Fantasy XII’ and there are these arches that looked exactly like something I had just studied that day in art history,” DeLucia recalls. “I started seeing all the relationships between the real world and this fictional world, how they altered things to make it fit, and I thought, ‘I want to be a part of that.’”

Sharpe draws his own inspiration from games designed by studios like Thatgamecompany, which published “Flower” and “Journey.” In “Flower,” players control the wind, blowing petals through the air and painting fields with color. “Journey” is a co-operative trip through a desert played with an anonymous online counterpart. Both games discard the mechanics- driven, action-focused experiences gamers are used to and focus on something more ineffable. For Sharpe, the results are unusually moving.

“The story in ‘Flower’ is very loose, almost nonexistent,” Sharpe says. “It’s about transformation. It taught me you can have this very heavy atmospheric experience that is deeply affecting.”

He chose Gossamer Games for the name of his studio because he wants to capture something abstract — the thin, fleeting moments in life that can’t quite be put into words but that carry so much weight.

“I want to explore games as an empathetic medium and as a means for not only storytelling but communicating abstract emotions,” Sharpe says. “Some experiences and emotions can only be communicated through doing something, and I think play is a perfect medium for that. It lets you explore different perspectives and see things in a different light.”

That intention shines through in “Sole.” The game is immersive, owing in large part to Ansari’s pensive score and the simple but effective premise. Wandering the world Gossamer has built and filling it with light feels like an act of creation in itself.

After years of work, the Gossamer team is anxious to see how the experience they’ve dreamed up will play with the public.

“The environment has to carry itself,” De Tommaso says. “If we did it right, people will come away being curious. They’ll want to find out more about the world that we’ve created.”

Commercial Success: In 2017, Gossamer Games was hired by the Science History Institute in Old City Philadelphia to create a first-person mobile game that will help visitors engage with the institute’s collection of art, books and artifacts related to medieval alchemy. Funded by a $100,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Gossamer’s Age of Alchemy: The Goldsmith’s Daughter invites players on a puzzle adventure that takes them through the “golden age” of alchemy in mid-17th century London.

Though the game is still in final development, the team has started to get recognition for it. “Sole” won for Excellence in Mobile Gaming at the 2016 Rensselaer GameFest. (At the time it was still intended first and foremost as a mobile game, but it’s now set for a multiplatform release.) It was nominated for an International Mobile Gaming Award in February 2017, and earned a spot at the Intel University Games Showcase last March. Gossamer raised $16,000 from 268 backers on Kickstarter to fund the game’s completion, and this winter it announced the game will be launching on Xbox One, opening it up to a wide audience.

With momentum at its back, “Sole” could break through to find success. If it does, Gossamer would help to realize Lee’s vision of a community of game developers setting down roots in Philadelphia.

The Art of the Game

In 2012, long before Sharpe had started thinking about “Sole” and before the Entrepreneurial Game Studio even existed, he went to Washington, D.C., to see an exhibit on the art of video games at the Smithsonian. Among the game developers present was the team from Thatgamecompany.

At the time, Sharpe was still tangling with his own ideas about the moral and cultural value of games, whether they truly mattered at all. It took him nearly 20 minutes to muster the courage to ask the creators of his favorite games about the creative process that fueled their unique visions, but he came away with a newfound confidence in himself and his ideas.

“I don’t know if I’d be doing what I’m doing if I hadn’t had that conversation with them,” Sharpe says.

Five years later, at another event at the Smithsonian last summer, he and the Gossamer team got to show off their own game. For hours, people streamed by — young and old, video game novices and veterans alike — and took “Sole” for a test run. They took control of the ball of light and entered the world Sharpe had dreamt up. The response was overwhelmingly positive.

“It was proof,” Sharpe says, “that all those years of hard work were truly worthwhile.”