In an unfinished, very new-smelling conference room on the ground floor of the Summit at University City, Ryan Monkman ’12 adjusts his hard hat and begins to tell his story. He talks over two fire alarm drills and ignores dings and vibrations from his iPhone. Yes, he knows it’s a hectic time, with the building just days away from officially opening, but he’s talking shop right now. He’s talking about his baby.

Monkman, a civil engineering grad, is the assistant project manager for the recently completed Summit project, a 24-story high-rise residence that has redefined the University City skyline. He was on the job, practically every day, for two years. Monkman managed the subcontractors, the scheduling and the budget for the building’s interiors.

“Anything from drywall to cabinets to painting in the individual units, the ground floor and the dining hall…everything that’s inside the enclosure that’s not electrical or mechanical, that’s me,” he says.

Through his job with Hunter Roberts Construction Group, the Summit project’s general contractor, Monkman was able to see the building materialize from paper renderings to its ultra sleek and urban finish. It was Drexel, along with the Hunter Roberts team’s confidence in Monkman, that made this possible, he says.

When he thinks back to day one on his first of three co-ops with Hunter Roberts, he laughs. He walked in fresh-faced and outfitted in a selection from his newly purchased business-casual wardrobe, ready to start in his role as an estimator, a position he knew nothing about.

“I didn’t even really know what construction was, or even what professional stuff was,” he says.

And all around him, he recalls, the “grown-ups” were freaking out. Something else was going on that day.

“Here I am, on my first day of my first co-op, my first big-person job, and it’s the day that Wall Street hiccupped,” Monkman says of the 2008 stock market crash.

Luckily for Monkman, he dodged any ensuing staff cuts and downsizing and wound up with much more responsibility than past co-ops had. He took the opportunity and ran with it.

Monkman’s second co-op was again as an estimator (essentially, the person responsible for “bringing in all the numbers” and running the job at the lowest price possible) and his third was as an assistant project manager, an in-the-field position Monkman coveted after two mostly office-bound jobs.

Along the way, Steve Markley, Hunter Roberts’ vice president of pre-construction and a 1980 Drexel alumnus, learned Monkman had staying power.

“He is such a hard worker — he works nights and weekends, he’ll take a second shift for his superintendent. There is nothing this kid won’t do,” says Markley.

That hard-working professionalism is something that Markley has come to expect from Drexel co-op students.

“We don’t have anyone on our staff, and especially the students from Drexel, who we don’t see as future leaders of our company,” he says.

After his co-ops with Hunter Roberts helped him develop a solid love for the industry, Monkman was faced with a harsh reality. It was 2012 and nearly time to graduate, and Hunter Roberts didn’t have any room on staff.

“I was crushed, but optimistic,” he says. “I knew no matter where I wound up I was going to kick ass.”

But Monkman stayed in touch, and a year later, he got the call he was waiting for. A spot at Hunter Roberts had opened up at Drexel’s Chestnut Square, another third-party residential project built by American Campus Communities with Hunter Roberts as the general contractor. The building was halfway complete, and they needed an assistant project manager to finish the job.

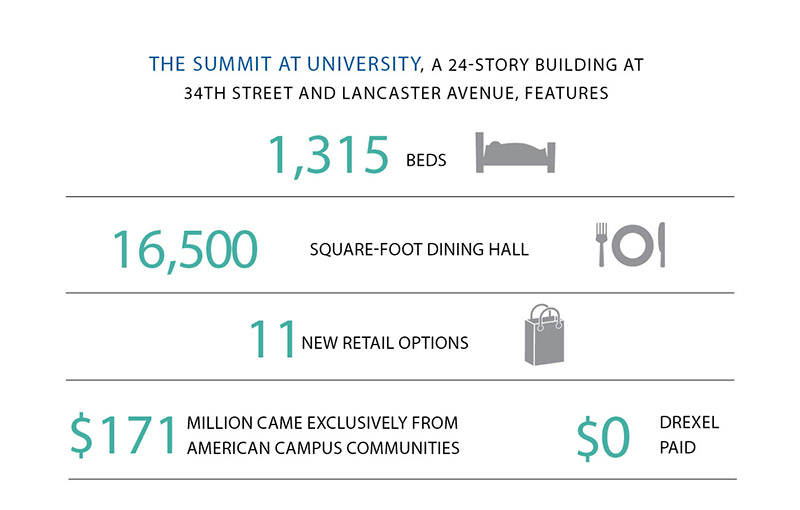

Chestnut Square was another of the University’s ventures with American Campus Communities, one of three total to date. Under the partnership, the developer builds and manages residences at its expense on land owned by Drexel, which the University leases to the development company. The partnership enhances Drexel’s campus amenities without making a dent in the University’s capital.

“This is a newer way to develop that a lot of public-style entities are moving toward,” Monkman explains. “It’s called public-private partnership, where the owner [in this case, Drexel] allows a developer [ACC] to build and profit while typically the costs do not hit the owner of the land. This allows Drexel to build bigger and faster without having to find specific funding.”

It’s the mark of a “smart” university, says Markley.

“It boggles my mind that more universities are not pursuing this option for student housing,” he says. “In my mind, there is no downside to it.”

Chestnut Square opened in 2013 and the Summit opened this past fall. For Monkman, both projects were exciting, intimidating, amazing, pure madness — and he wants more.

“This is an amazing time in Philadelphia,” he says. “There is so much development going on, so many things happening. I can see myself building 100 of these buildings and just working my way up to as high-level as I possibly can. In this industry, every day, every project, every problem is different; you could do this for 40 years and still not know everything.

“But for right now, I’m happy where I’m at. I’m on top of the world.”